Arc’teryx Is Cooked in China

Chinese consumers' generational value clashes behind the terrible marketing move

Last call for our China tour in Shanghai & Hangzhou, taking place October 27–30. This consumer and tech discovery tour will visit companies that represent China’s growing consumer and technology sectors, such as Alibaba AI, Deep Robotics, Proya, and JNBY Group. Check out the full itinerary here.

On September 19, Chinese firework artist Cai Guoqiang and outdoor apparel brand Arc’teryx jointly staged a fireworks display called “Ascending Dragon” (“升龙”) in Relong Township, Gyantse County, in the Tibet Autonomous Region. The display — set at roughly 5,500 meters altitude — consisted of three sequences of fireworks along the Himalayan mountainous ridge, with imagery meant to evoke a dragon — a powerful symbol of vitality and prosperity and one of the most enduring cultural totems in Chinese history.

Soon after videos of the event circulated online, the display triggered intense backlash over environmental and cultural concerns. Netizens began calling for a boycott of Arc’teryx, arguing that setting off fireworks in such a fragile alpine ecosystem risked disturbing wildlife, damaging slow-growing vegetation, and polluting the high-altitude environment. Many also criticized the spectacle as disrespectful to local traditions, which hold mountains as sacred and discourage loud disturbances. The sponsored firework show is the complete opposite of environmental protection and respect for nature—values that strongly resonate with China’s affluent urban middle class and outdoor enthusiasts, who form Arc’teryx’s core customer base.

Some netizens have even extended the boycott to Anta Sports (2020.HK), the Chinese sportswear conglomerate that acquired Arc’teryx’s parent company, Amer Sports (AS:NYSE), in 2019 and now effectively owns the brand.

It’s evident that the firework installation had terrible aesthetics and was an obviously poor idea for an outdoor brand, yet it’s just uncanny how such a decision was made. Many are struck by the fact that both Cai and the Arc’teryx team initially seemed to enjoy and celebrate the show as a huge success.

In today’s newsletter, I want to give you more context on what this controversy reveals about Chinese consumers — and why the backlash goes beyond environmental concerns to reflect deeper social and cultural shifts.

How Arc’teryx managed to anger the full spectrum of Chinese consumers

Speaking generally (and perhaps a bit stereotypically), Chinese consumers have very different values and attitudes toward brands. Urban middle-class consumers and those living in more remote regions, rural areas, or less economically developed cities often care about completely different things.

For example, we’ve previously discussed how nationalism can be an effective marketing tool for certain consumer segments — particularly those from less economically developed regions or with limited exposure to foreign culture. These consumers might feel justified boycotting Nongfu Spring bottled water just because nationalist influencers claimed the bottle cap resembled the Japanese flag. The same narrative, however, generates almost zero resonance among the urban middle class.

The fact that Cai Guoqiang’s fireworks show, sponsored by Arc’teryx, managed to get both groups to finally agree — and get angry at the same time — shows just how little the team understood the Chinese consumer market.

The rising urban middle class

“ESG” — a concept that originated in the 2000s and gained significant material impact in North America and Europe — has existed in China for years, but mostly as a buzzword. For a long time, corporate references to “environmental friendliness“ or “social responsibility“ were treated as nice-to-have branding or merely compliance with basic regulations, rather than as priorities with real financial impact. For one thing, investment decisions in China were rarely bound by ESG mandates, and it's common for consumers to choose price and convenience over whether a brand truly embodied ESG values. (Realistically speaking, many consumers simply lacked the awareness, tools, or access to evaluate how a company performed on ESG benchmarks.)

But that is changing. In recent years, China’s urban middle class has begun voting with their wallets, willing to spend real money to support brands that align with their values.

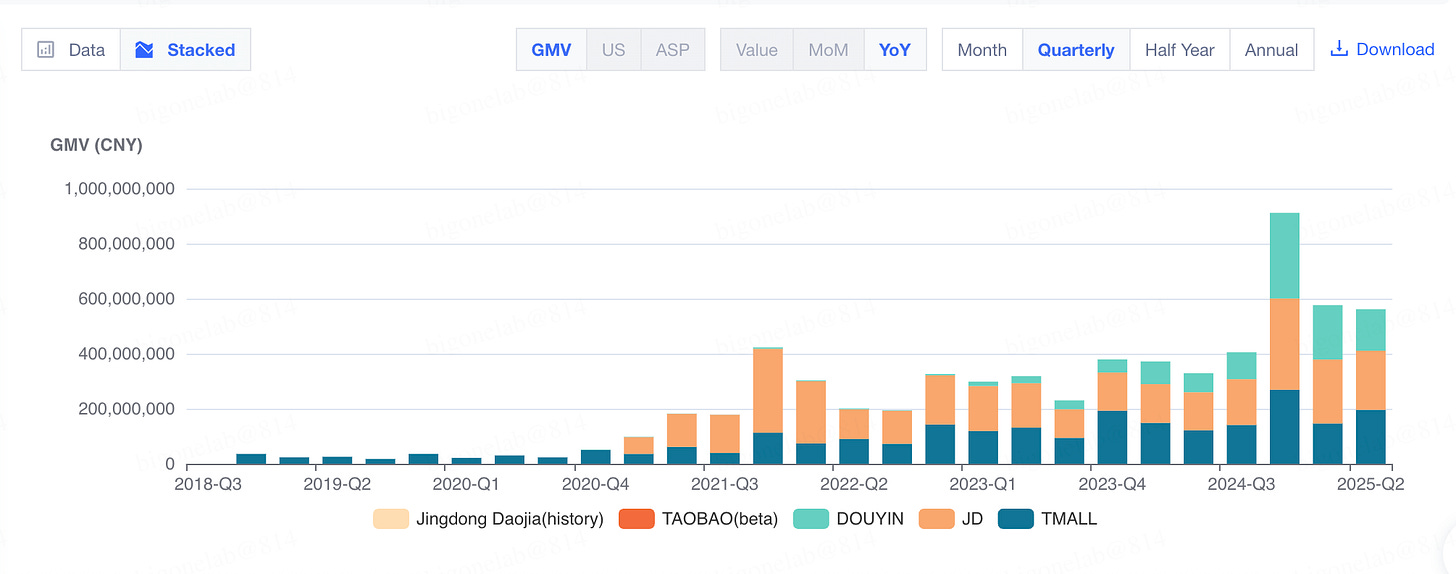

Arc’teryx has seen spectacular expansion in China thanks to the post-COVID boom in outdoor sports. In Q1 and Q2 this year, the brand posted double-digit year-on-year sales growth despite the broader consumer slowdown — proof that demand from affluent consumers remains robust. But its increasingly aggressive expansion in China has also widened the gap between its current positioning and the values that originally built its reputation as a professional outdoor brand.

Arc’teryx, which first won over hardcore outdoor enthusiasts in the 1990s with its technical hardshell jackets, has in recent years faced criticism in China for drifting away from its image as a serious outdoor brand.

On Chinese social media, Arc’teryx is sometimes playfully called an example of “厅局风” — literally “bureau-chief style” — referring to understated but pricey outfits that project status and authority. The look is polished and professional, but its purpose is more about signaling taste and success. This trend reflects the brand’s growing popularity among city dwellers who appreciate its design and quality but may wear it mostly in urban settings rather than on the mountain. They may not be diehard outdoor enthusiasts, but they form a large base of affluent Chinese who can afford a jacket like Arc’teryx. For critics, this shift has turned Arc’teryx into more of a status symbol — a way to signal an “outdoorsy” lifestyle — rather than a brand strictly defined by its pure outdoor performance.

Many outdoor enthusiasts argue that Arc’teryx’s management has lost touch with the outdoor spirit that once defined the brand. They point out that a true outdoor enthusiast would never have approved a fireworks show that risks damaging the very landscapes where Arc’teryx gear is meant to be worn. To them, the backlash over the event felt less like a one-off mistake and more like the inevitable result of a brand now led by people who no longer live and breathe the outdoors.

Apart from environmental issues, China’s urban middle class — especially those born in the 1980s and 1990s — is paying more attention to how socially responsible companies are. For example, this year more and more netizens are boycotting products from companies that follow the “996 schedule,” the notorious work culture requiring employees to work 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week, often without clear overtime pay. On Xiaohongshu (Red Note), people are sharing lists of companies that mistreat employees and avoiding their products.

The conversation hasn’t yet reached a level that creates real, measurable impact on companies. (And, frankly speaking, it’s hard to determine which brands are fully compliant across their supply chains). But the fact that more young consumers are talking about it shows the urban middle class is shifting toward values-driven purchases, not just buying based on price or convenience — a mindset closer to what one would see in North America and Europe.

Conservative and traditional consumers in lower-tier cities and rural areas

The fireworks show happened on September 19, just one day after September 18, a sensitive date for all Chinese people, as it marks the anniversary of the Mukden Incident—the pretext for Japan’s invasion in 1931 and the beginning of a decade of national tragedy and historical humiliation.

Many netizens escalated their anger, discussing whether the artist Cai Guoqiang and his family hold foreign passports or permanent residency. It’s not actually clear whether they still hold Chinese passports, but both of Cai’s daughters were born and raised abroad (in Japan and the US).

The broader context is that celebrities and entrepreneurs who hold foreign passports or PR while continuing to monetize within mainland China have become a sensitive—and often problematic—image, and Cai is far from a unique case.

For instance, in my previous newsletter, “The Fall of China’s Iconic National Brand,” I discussed how obtaining foreign green cards or sending second-generation children abroad shifted from being a widely accepted practice among Chinese elites to a sensitive issue that now requires discretion in recent years:

Following China's decades of rapid economic growth, it became common—almost standard practice—for successful entrepreneurs and affluent families to obtain foreign green cards or passports, most notably from the United States and Canada. It also became standard practice for business leaders to send their children—the so-called second generation—to study abroad, with the U.S. and Canada again being top destinations.

These were as much personal choices as strategic ones. For companies seeking global markets or planning to IPO overseas, registering in the Cayman Islands was considered a standard step for accessing foreign capital markets.

But in today's charged social atmosphere, these once-routine practices have become dangerous liabilities. Some consumers now question the national loyalty of business owners. A foreign passport or offshore holding company can be twisted into damning "evidence" of betrayal. Whether a company is a true "Chinese national enterprise" carries far more weight today than ever before.”

Even Aileen Gu, the Chinese-American skiing athlete who won gold for the Chinese team at the Beijing Winter Olympics and has done absolutely no apparent harm to China, received very mixed reviews on Chinese social media. While many praised her sporting excellence and personal character, a large number of netizens expressed resentment over her (unconfirmed) dual identity and ambiguous nationality. At the end of the day, it’s simply a fact that many Chinese consumers do feel a disconnect with celebrities like her, seeing them as elites who lack awareness of their privilege and who make money in China without being “100% Chinese.”

Cai Guoqiang, given his family background and the timing of the fireworks show on a sensitive date, has undoubtedly become a target of Chinese netizens. The use of “dragon” imagery also sparked widespread discontent over potential cultural appropriation among Chinese netizens, with some even accusing Cai of deliberately sabotaging the Feng Shui of the mountainous region, where they believe the Dragon vein lies.

Many bluntly wrote on social media: “I’m not a target client of Arc’teryx, and I admit I can’t afford one, but I will boycott all brands under Anta Sports.”

While Arc’teryx does not account for the majority of Anta Sports’s total revenue, it is a substantial and fast-growing component of Anta’s “multi-brand, globalization” strategy. The anger among non-core Arc’teryx consumers will probably fade quickly, but it is worth monitoring whether resentment toward Anta as the parent company continues to fester. (We can share some data insights in the coming months.)