China is short on crude oil!

A historical and geographical overview of China's crude supply

When Chinese people think of China, many often describe it with the phrase "地大物博," which means "vast land and abundant resources." However, this is somewhat misleading. In reality, China is more accurately described as "地大物不博," or "vast land but limited resources," as many natural resources are actually scarce, such as forests, arable land, and oceans, especially on a per capita basis. Oil, as a crucial energy source, is particularly limited in China.

China transitioned from an oil exporter in the 20th century to a major importer by 1993, with consumption skyrocketing to 7.1 million tons in 2022. Despite being the sixth largest producer, China's oil production falls short of its significant consumption needs, relying on imports for over 70% of its supply.

In today's newsletter, we want to share an excellent article by the Earth Knowledge Bureau, a widely-read independent science media outlet on WeChat (ID: diqiuzhishiju). The article provides a comprehensive overview of how China transitioned from being a net oil exporter to heavily relying on oil imports, as well as the reasons behind China's current shortage of crude oil.

In addition to the historical and geographical overview, the article also sheds light on the motivations behind China's investments in renewable energy as a way to reduce oil dependence. We believe this article will be an interesting addition for anyone interested in gaining a contextualized understanding of China’s approach to oil independence and renewable energy.

This post is sponsored by BigOne Lab, our parent company. BigOne Lab proudly announces the introduction of China Mobile Payment dataset, covering high-frequency offline sale performance of brands such as LULU, Hermes, LV, Starbucks, POP MART, Miniso sportswear, luxury, coffee and tea chains and speciality retail sectors that were previously undercovered by data. If you are interested in subscribing, please contact more@bigonelab.com

Below is our translation of the original article, titled "中国现在,非常缺石油" (China is Short on Crude Oil)". Some images have been abbreviated.

China is short on crude oil

Black gold, the lifeblood of industry, the trump card for Middle Eastern tycoons, the dominant force in the commodities market.

Oil, as the most important energy source since the 20th century, has profoundly influenced the course of history, determining the rise and fall of nations. Oil has fueled the rise of the United States and the Soviet Union, constrained Nazi Germany and militaristic Japan, and rendered countries like Brunei and Norway extraordinarily wealthy, while leading to the downfall of nations such as Iraq and Libya.

For modern states, securing a stable oil supply is crucial to national fate.

Once, China was an oil exporter. With the production of major oil fields like Daqing, Shengli, and Karamay, China's crude oil output quickly surpassed 100 million tons. Starting in 1973, China even exported crude oil to Japan to earn foreign exchange. However, by 1993, China had become an oil-importing nation, with oil consumption reaching 150 million tons that year.

Cities like Daqing have thus become renowned 'oil cities' in China. Let's see the current state of these oilfields (on the right).

In just 17 years, by 2010, China overtook the United States to become the largest manufacturing country, with oil consumption rising to 440 million tons. By 2022, consumption soared to an astonishing 710 million tons, accounting for 15% of global production, second only to the U.S. at 820 million tons. Unlike the U.S., however, China's oil supply is heavily reliant on imports. In 2022, over 70% of the 710 million tons consumed was imported.

Oil is not only the lifeline of industry but also essential for agriculture and logistics. The consequences of an oil shortage can be dire, as exemplified by North Korea in the 1990s. Thus, enhancing domestic oil production capacity and ensuring stable oil imports are of paramount strategic importance.

Why is China facing such a severe oil shortage? What are the potential solutions? Today, we will discuss the issue of oil scarcity in China in detail.

China's own oil is not enough

China's oil shortage stems from a significant disparity between reserves, production, and consumption.

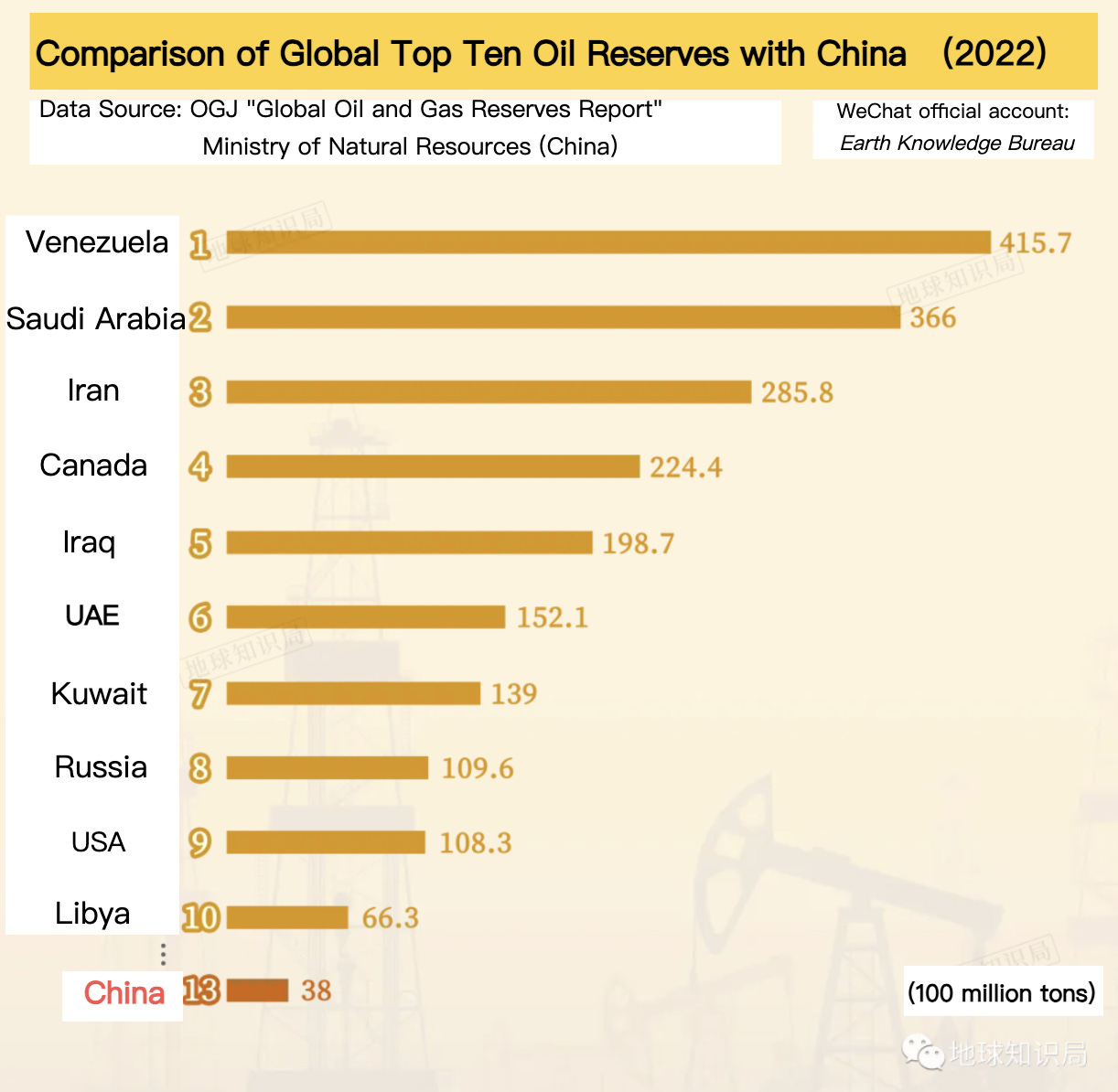

According to data from the Ministry of Natural Resources (China) (2022 National Mineral Resource Reserve Statistics Report), as of 2022, China's oil reserves were approximately 3.8 billion tons, accounting for only about 1.58% of global reserves, ranking 13th in the world.

Whether in terms of reserves or production, Middle Eastern countries are undeniably the dominant oil players.

Despite having relatively low reserves, China remains the sixth-largest oil producer globally. However, this is insufficient to meet its demand.

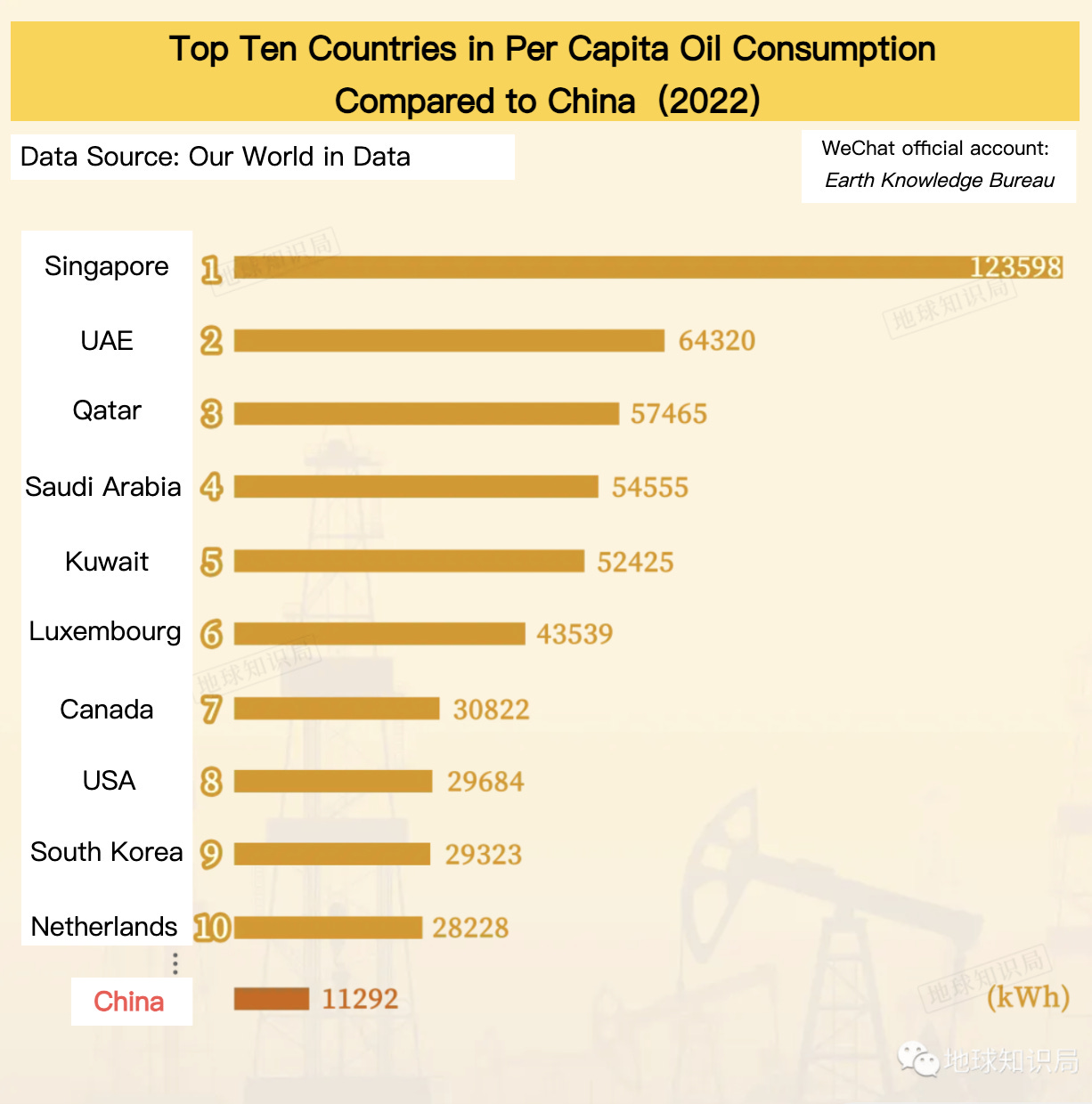

The OPEC report from December 2022 indicated that China consumes 14.79 million barrels of crude oil daily, ranking second globally.

With the 13th largest reserves and 6th highest production, China's 2nd highest demand means even three Saudi Arabia wouldn't suffice, especially given our per capita consumption is much lower than that of the U.S.

The root cause of this oil shortage lies in natural endowments.

Theoretically, large-scale ancient sedimentary basins are likely to generate oil and gas-rich regions, as seen in the Gulf of Mexico, Lake Maracaibo, Saudi Arabia's Ghawar Oil Field, and Alaska's North Slope.

While significant sedimentary basins usually form in oceans, most of China's basins originate from terrestrial lakes. You can imagine the size difference between oceans and lakes; their resource volumes are not even in the same league.

Moreover, many of China's sedimentary basins have been severely damaged during geological evolution, resulting in fragmented geological structures.

Experts liken the strata of sedimentary basins to a plate: oil-producing nations have intact plates, while China's basins resemble shattered plates that have been further crushed. Consequently, when drilling, we may only tap into a small portion of the target layer, leading to low oil and gas output and short production cycles.

Additionally, another disadvantage is the depth at which oil is buried in China, which is generally deeper than in many other regions.

For example, oil wells in Xinjiang typically require drilling depths of 7,000 to 8,000 meters, and even then, oil may not be reached. In contrast, countries with better oil endowments like the Middle East, Central Asia, and Australia generally have wells that are only 1,000 to 2,000 meters deep, yielding higher quality and quantity of oil.

Saudi Arabia's Ghawar Oil Field, a national treasure, has a productive layer depth of 2,200 meters, with proven reserves reaching 10.74 billion tons—almost three times that of China—at costs under $10 per barrel, which is globally unmatched.

While China's ability to drill near 10,000-meter-deep wells—currently the deepest drilling depth in China—showcases technological strength, it is also a reflection of the limitations imposed by resource endowments. In terms of extraction costs and cost-effectiveness, importing oil is often more economical than domestic production.

China does possess shallow, high-yield oil fields, but most are aging fields nearing depletion. For instance, the Daqing Oil Field's comprehensive water cut has reached 95%, making stable production increasingly challenging with output declining annually. At this point, they're squeezing out the last drops.

Recent discoveries of large oil fields have generally been difficult and costly to develop. For instance, the Mahu Oil Field (Xinjiang, China) is located at an elevation of 340-500 meters and is classified as a tight sandstone oil field, where oil is concealed in nearly invisible rock pores, making full development of such fields a formidable global challenge.

In reality, aside from a few countries like Saudi Arabia, many regions worldwide are grappling with the depletion of shallow oil and gas reserves. Although predictions of imminent oil shortages have not materialized, drilling is increasingly deeper, shifting from shallow to deep and ultra-deep layers. In recent years, 60% of new global oil and gas reserves have emerged from deep layers.

While our extraction technology is advancing, allowing us to drill nearly 10,000-meter-deep wells and achieve breakthroughs in unconventional oil and gas resources like shale oil, shale gas, coalbed methane, and tight limestone gas, large-scale increases in production remain extremely challenging due to technical and cost limitations.

Even with advancements in technologies for shale oil, oil sands, and deep-water fields, achieving significant production increases in the short term remains a challenge, making continued imports necessary.

The super buyer's dilemma: China as a leading oil importer

China has exceeded the international oil import dependency threshold of 50% for many years, accounting for a quarter of global oil imports as a super buyer.

China's oil import volume has consistently increased.

As a super buyer, it is crucial to diversify and maintain reliable sources of supply to avoid dependency on single sources. Fortunately, the global oil production focus is shifting to Asia, which is geographically advantageous.

This cooperative relationship is evident in the nighttime lights visible from space: from East Asia to Southeast Asia and South Asia, many of the lights are generated by massive populations, cities, and industries, while the lights of the Middle East, Central Asia, and Siberia often stem from oil and gas fields. This interconnectedness facilitates mutually beneficial cooperation between Asia's two major economic systems through oil tankers and pipelines.

China is a key player in the buyer camp, but not the only one. India, also in the monsoon region, has an even higher oil import dependence rate of 85%, emphasizing the importance of relationships with Gulf countries. Last year, India aggressively purchased low-priced Russian oil, mirroring China's import composition.

Before 2022, 60% of India's crude oil imports came from the Middle East.

In 2022, China's oil imports amounted to 2.43 trillion RMB, with Saudi Arabia and Russia supplying over 80 million tons each, followed closely by Iraq, the UAE, Oman, Malaysia, Kuwait, and Angola.

This import composition is constantly changing, influenced by the geopolitical landscape. For instance, since 2019, due to international sanctions and political unrest, oil imports from Iran and Venezuela have significantly decreased, although alternative sources remain plentiful.

Even with a relatively stable import composition, fluctuations in international oil prices can greatly impact economic security. For example, during the significant drop in oil prices between 2014-2016, China's oil import costs decreased markedly. Conversely, in 2019, a drone attack on Saudi oil facilities led to a spike in global oil prices.

A disruptive attack on Abqaiq would be like a massive heart attack on the oil market and the global economy.

The East Asian model of importing raw materials and exporting finished products is highly sensitive to resource price fluctuations, especially in times of unrest and conflict.

Thus, it was essential for China to import large quantities of oil at low prices at the end of 2018 to expand its strategic reserves and sign a long-term contract with Russia.

The contract signed in 2014 extends over 30 years, ultimately reaching an annual supply of 38 billion cubic meters. Starting in 2018, gas was supplied through the eastern route of the China-Russia natural gas pipeline.

Setting aside distant sources like Venezuela and Nigeria, the nearby oil-producing regions of Asia also face geopolitical risks. Maintaining peace in this area is crucial for solidifying the continent-wide cooperative relationship between these two major economic systems.

Even with stable sources of imports, transportation remains a challenge.

While pipeline transport is relatively stable, constructing new pipelines is complex. Connections to Russia and Central Asia are relatively easier, but direct connections to the Middle East remain challenging, and pipeline capacities are also limited.

Consequently, maritime transport is unavoidable. As discussed in previous videos on the Malacca Strait and Arctic routes, the Arctic route is currently unrealistic, while shortcuts from Pakistan's Gwadar Port and Myanmar's Kyaukphyu Port are unlikely to develop sufficient transport capacity. The Kra Canal remains unreliable.

Almost all East Asian oil imports must pass through the Malacca Strait.

Concerns about potential chokepoints in the Strait of Malacca are prevalent; in reality, there are numerous choke points, such as the Strait of Hormuz, particularly with the significant presence of India in the vicinity. This illustrates the critical importance of maritime power. For China, as a super buyer, maintaining a stable oil supply is incredibly challenging.

As the "choke point of the Gulf," the Strait of Hormuz often experiences heightened tensions.

Solutions: diversifying sources and optimizing energy use

Given China's limited resources and the instability of oil imports, what are the viable solutions?

The specific solutions are simply to diversify sources and optimize energy use.

The first priority is to diversify oil import sources to reduce dependency on specific countries. This involves increasing imports from oil-rich but economically less-developed nations, such as Angola, the Republic of Congo, and Kazakhstan. By investing in joint ventures for oil exploration and production, China can secure more stable supply channels. Chinese companies have actively invested in Angolan oilfields, ensuring a steady export flow from these ports.

On the domestic front, China's oil production capacity still holds significant untapped potential. By leveraging advanced exploration and extraction technologies, we can ensure the long-term viability of existing fields and reduce unnecessary waste. The potential of shale oil, oil sands, and deep-water oilfields is significant; although their current contribution is low, it is expected to increase over time.

If we allocate some resources to develop unconventional types of oil, there is still significant room for our growth.

In terms of curbing demand, reducing overall energy consumption remains challenging, but diversifying the energy structure is key and holds significant potential.

In the past five years, the proportion of renewable and clean energy sources, represented by wind, solar, hydro, and nuclear power, has increased by 5% (from 20.8% to 25.9%). However, oil accounts for only 3.1% of our power generation structure, while coal makes up 36.5%.

As an oil-scarce nation, China uses minimal oil for power generation, yet consumption in transportation and industry is substantial. The rise of electric vehicles reflects a strategy to indirectly substitute oil with other energy sources—a clear response to China's oil shortage. Without curbing consumption, the already significant gap between our production and demand will only continue to widen.

The current drive to promote electric vehicles is well-founded.

These combined measures may enable China to transition steadily toward a more self-reliant energy structure. With technology advancing rapidly, oil's dominance is far from guaranteed. Middle Eastern oil giants, too, are ramping up investments for a future beyond oil.

Ultimately, the most enduring solution to China's oil shortfall may be the arrival of an era where oil is no longer critical. While this future isn't right around the corner, it may well arrive within our lifetimes.