China's demographic paradox: empty cribs and full pet beds

Is China's new childbirth subsidy going to work?

In numerous kindergartens throughout China that were formerly hard to get in, classrooms originally designed for 30 children currently hold scarcely half that number. Meanwhile, newly opened pet grooming salons are booked solid for weeks, with services ranging from basic trims to elaborate spa treatments for the neighborhood's pampered pooches.

This scene is playing out across China, where the nation faces a demographic crisis that continues to deepen. For the third consecutive year, China's population has declined, dropping by 1.39 million in 2024 to 1.4083 billion. While the birth rate showed a modest increase from 6.39 births per 1,000 people in 2023 to 6.77 in 2024, deaths still outnumbered births, with 10.93 million people dying last year—pushing the death rate to a five-decade high.

The slight uptick in births—9.54 million babies in 2024 compared to 9.02 million in 2023—offers little comfort to policymakers. That 2023 figure represented the lowest number of newborns since record-keeping began in 1949, and the modest recovery in 2024 is attributed partly to the Year of the Dragon, traditionally considered an auspicious time for childbirth in Chinese culture.

Yet amid this birth drought, another trend is flourishing: young Chinese are increasingly channeling their parental instincts toward pets, creating a booming industry catering to "fur babies"; some even lavish generously on luxury products and services that were once exclusively reserved for humans.

This shift raises profound questions about China's future: Is money really the main obstacle to having children? Or are deeper cultural and lifestyle changes reshaping what family means in modern China?

Hohhot's bold bid to boost births

In some cities, local governments are implementing increasingly generous subsidies to encourage childbearing. For instance, the city of Hohhot has recently launched what might be China's most aggressive birth incentive program yet.

Starting March 1, 2025, parents in this northern city of 3.6 million will receive substantial cash rewards for having children: a one-time payment of 10,000 yuan ($1,394) for a first child, annual payments of 10,000 yuan for five years for a second child (totaling 50,000 yuan), and annual payments of 10,000 yuan for ten years for a third child (totaling 100,000 yuan).

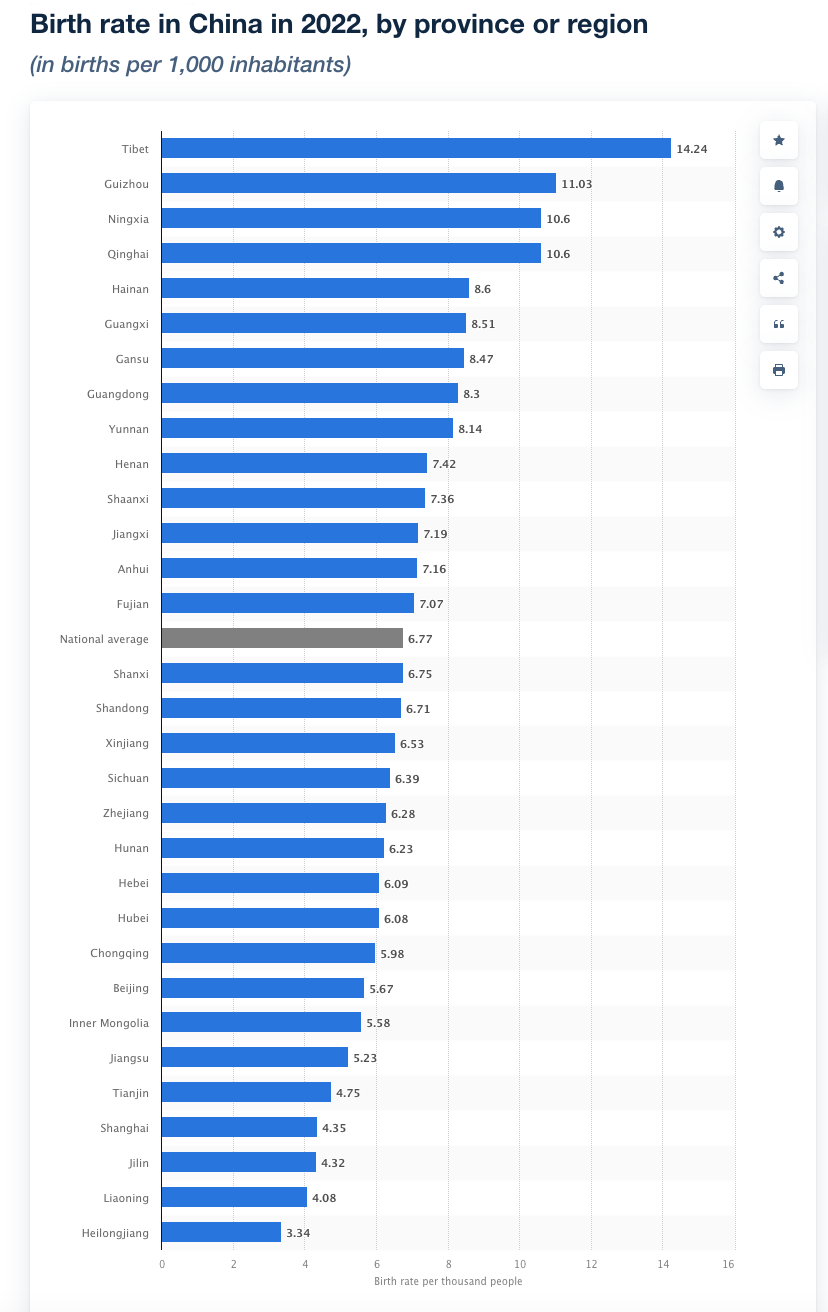

The urgency is clear: Hohhot's birth rate stood at just 5.58 births per 1,000 people in 2023, below the national average of 6.39 [*].

Hohhot's program represents a significant escalation in China's efforts to reverse its demographic decline. Since abandoning the one-child policy in 2015 and further loosening restrictions to allow three children per family in 2021, the government has shifted from limiting births to actively encouraging them. But will throwing money at the problem work?

The paradox: Why rich provinces have fewer babies

When it comes to having children in China, a counterintuitive pattern manifests: the wealthier regions do not necessarily see more childbirths. This demographic paradox poses a challenge to the conventional wisdom that financial stability leads to larger families.

For instance, in 2022, Shanghai—China's financial powerhouse—recorded just 4.35 births per 1,000 residents, while remote Tibet registered 14.24, more than three times higher. Other wealthy regions like Jiangsu (5.23) and Beijing (5.67) similarly lag far behind less developed provinces like Guizhou (11.03) and Ningxia (10.6).

The economy is not the sole factor either. For instance, Guangzhou, another relatively economically affluent province in China, ranked high in the nationwide birth rate with 8.3 births per 1,000 residents - largely attributed to the cultural and traditional belief that having large families is a sign of prosperity in the region.

Fur babies over human ones: China's pet parenting boom

However, on the other end of the spectrum, numerous young Chinese individuals are treating their pets as if they were their babies.

"People are very willing to spend money on pets, especially Shanghai residents," says Zang Shuo, a fashion design graduate who pivoted from human couture to pet clothing. Her business offers custom-designed pet outfits ranging from 200-400 yuan each, with some clients ordering new clothes monthly. "They basically all take their pets out in little strollers, and every season they travel with their dogs. There are almost no 'naked dogs' here—they all wear clothes."

Although the price range of 200-400 yuan exceeds that of many children's clothing (not to forget that the one-time subsidy for the first birth in Hohohot is 10,000 yuan), pet owners do not hesitate at such a price.

The trend extends beyond basic necessities to luxury items and services. Pet owners request Burberry-style coats and Gucci-inspired accessories. They book pet spa treatments, professional photoshoots, and even pet summer camps. Some pets have their own social media accounts with thousands of followers.

Zang Shuo shared her observation (reported by 36Kr, translated below):

In recent years, the outdoor style has been very popular. This trend has also extended to the dog world, and dogs are now starting to wear "Arc'teryx". When I was in school, my teachers often asked us to design clothes with functional fabrics to improve their practicality. I thought I could apply the same concepts used in human clothing design to dog clothes. For example, I could sew a mosquito repelling patch on the corner of the dog's clothes to protect them from mosquito bites. I could also use a retractable material so that the clothes can be used as a raincoat on rainy days. Another idea is to add a handle to the dog's clothes, so that you can carry the dog around like a handbag.

It's the same with clothes. When the competition in the human fashion world gets too intense, it spills over to the dog world. You know, in the past, large brand printed logos were very popular, and dog clothes also had prints of Gucci, LV and so on. Now that the outdoor style is trendy, there are so-called "Arc'teryx for cats" and "The North Face for dogs", which sell very well.

Some dog owners have their own unique ideas. For instance, one sent me a Burberry coat and asked me to turn it into a dog windbreaker. Another asked me to find Gucci fabric to make a dog coat full of logos. There's also the owner of a giant poodle. Every time he places a custom - made order, he has already selected the fabric and buttons himself, and has considered all aspects of the design and craftsmanship, like whether to have a lining for the clothes and what kind of material the lining should be.

Such scenes, once rare, are now increasingly common in China's urban centers. As birth rates plummet, a parallel trend is emerging: young Chinese are channeling parental instincts and disposable income toward pets, treating them with a devotion once reserved for children.

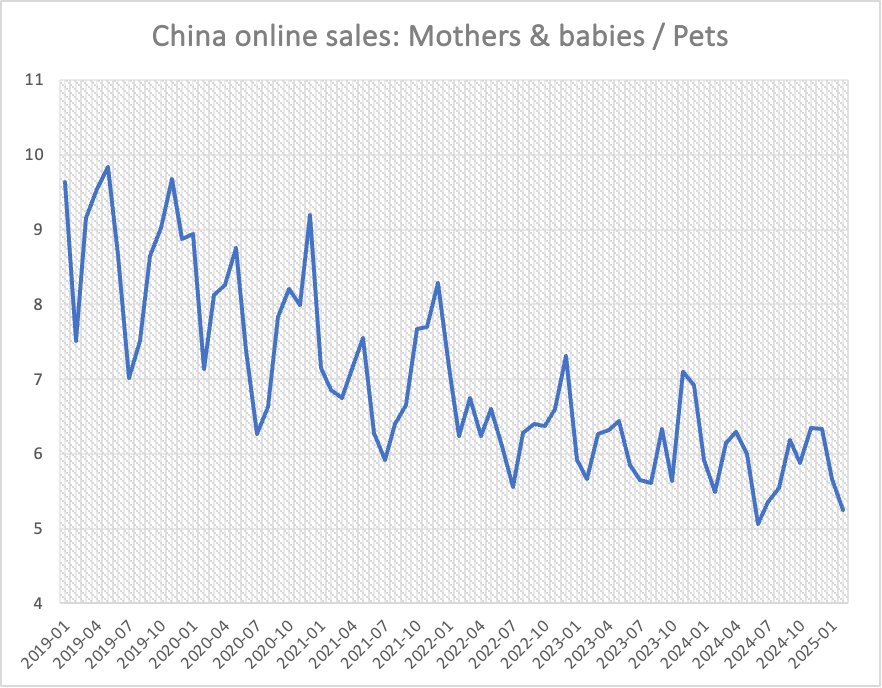

Our numbers back up this observation as well. Since 2019, online sales of mother and baby products relative to pet products have been on the decline, indicating that the pet product sector has been growing at a faster rate.

Pet parents also overlap with high-spending groups. Based on a study by Red Note, 66.9% of pet owners in China belong to the middle-to-high consumption group, which largely overlaps with the middle-class and above consumer group like Taobao 88VIP members [*].

During the 2024 Double 11 shopping festival (China's biggest online sales event), pet products saw explosive growth on e-commerce platforms. New brands are emerging rapidly, with some reporting sales growth of over 1000% year-over-year [*].

Even premium products find ready buyers. A high-end cat food brand priced at 680 yuan per bag sold out within minutes during a recent promotion. Pet travel accessories, healthcare products, and specialized toys are similarly flying off virtual shelves [*].

This shift in spending priorities raises profound questions about changing values in Chinese society. As young people increasingly refer to themselves as "dog parents" and "cat parents," they're redefining what family means in contemporary China.

What's really driving China's demographic shift?

The conventional narrative suggests young Chinese aren't having children because they can't afford to. Housing prices in major cities have soared beyond reach for many, education costs are high, and work-life balance seems increasingly elusive in a competitive economy. These financial pressures are real.

Yet this explanation falls short when we consider that many of the same young people who find children unaffordable are spending lavishly on pets. A Shanghai resident who balks at the cost of diapers might think nothing of spending 400 yuan on a designer dog jacket or 680 yuan on premium cat food. The annual cost of keeping a dog in China now averages nearly 3,000 yuan—a significant sum that many willingly pay.

In cities like Hohhot, the birth subsidy might be substantive. In 2023, the annual average wage of employees in urban non-private units and private units in Hohhot was 116,341 yuan and 58,498 yuan respectively [*]. An annual subsidy of 10,000 yuan is considerable compared to the average annual salary.

But in more economically advanced cities like Beijing and Shanghai, economics is no longer the sole consideration. Different from the parent's generation, where they feel starting a family is a must, for modern China's generation, family formation is increasingly a choice rather than an expectation.

The rise of pet parenting speaks to changing emotional needs in a fast-paced, often isolating urban environment. Pets provide unconditional affection, without the decades-long commitment and societal expectations that come with raising children. They allow young people to nurture and care for another being without fundamentally altering their lifestyle or identity.

And this is especially true for women. As regions become wealthier, education levels rise, women gain more career opportunities, and traditional family structures evolve. The cost of raising children in these areas also increases dramatically—not just financially, but in terms of time, career sacrifices, and lifestyle changes.

In more affluent cities and provinces in China, society often expects parents to invest enormous resources in each child to ensure their success. Many parents feel pressured to provide the best education, extracurricular activities, and social resources—this is the so-called "quality over quantity" mindset that was first promoted during the one-child policy and now becomes common in provinces like Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and first-tier cities, even after the one-child policy is in the history.

But with a pet, one can still travel, focus on a career, and maintain independence. Social media amplifies these trends, making pet ownership a lifestyle statement and identity marker in a way that parenthood, once taken for granted, no longer is.

So could China's new birth subsidies work? For regions like Hohhot, where 10,000 yuan represents a meaningful percentage of annual income, financial incentives may indeed move the needle. But the stark regional disparities in birth rates reveal a more complex picture—one where China's demographic future will be shaped not just by economic policies but by cultural transformations.

The path ahead might entail not merely subsidies, but a more extensive rethinking of what family, fulfillment, and social aspects signify for a generation trapped between tradition and transformation. For example, how work settings can offer better support to parents, how childcare duties can be shared more fairly, and how communities can furnish the emotional backing to the parents born under the one-child policy that once came from extended families.

*For interested readers, I had a conversation with my colleague Aaron on the issue of the low childbirth rate in China on our Youtube channel. Feel free to check it out and participate in the comment sections :