What happens when a nation built on growth runs short of babies?

From closing kindergartens to deserted maternity wards—how fewer babies are reshaping the economy, workplaces, and everyday life

Marriage numbers in China dropped again in Q1 2025.

The chart paints a rollercoaster story of marriage trends in China’s first quarters from 2012 to 2025, based on data from the Ministry of Civil Affairs. Marriages peaked at 4,282,000 couples in 2013—a golden year—before sliding down to a pandemic-struck low of 1,557,000 in 2020, where the blue line nosedives by 45%. A hopeful bounce to 2,132,000 couples (+37%) in 2021, but numbers kept going downward: 2,147,000 in 2023, then 1,969,000 in 2024, before settling at 1,810,000 in 2025.

The birth rate has been a frequently discussed topic due to its close relationship with China's economy. Just think about how China's past manufacturing boom, urbanization, real estate sector, and consumer market have all been intertwined with demographic trends. However, discussions on the birth rate have often been data-centric and abstract, with little attention paid to its real impact on people's daily lives, career development, income, and consumption behaviors.

In today's article, we will provide an in-depth look at:

The societal and cultural reasons behind the decline in birth rate.

The tangible effects of this decline on industries such as maternity wards, pediatrics, postpartum care centers, kindergartens, and the consumer goods market.

My personal analysis of the current fertility stimulation policies and potential future directions.

The root causes of China's demographic decline

China's plummeting birthrate can be traced to three interlocking factors that form a vicious cycle: the shrinking pool of childbearing-age women, collapsing marriage rates, and evaporating fertility intentions. These elements don't merely add up - they multiply each other's downward momentum, creating what demographers call a "triple demographic shock."

The vanishing childbearing-age population

At the core lies a generational time bomb. The number of women in their prime reproductive years (20-29) has undergone a staggering contraction, halving from 12.51 million in the 1990 birth cohort to just 6.33 million for those born in 2003. This dramatic shrinkage, a direct consequence of strict family planning policies after 1987, represents an irreversible demographic reality.

Compounding this baseline contraction is an aging effect within the remaining fertile population - the proportion of women aged 30-39 has ballooned from 32% in 2010 to 48% in 2023, bringing increased risks of pregnancy complications and reduced natural conception rates.

The marriage crisis: plummeting first-marriage rates and delayed unions

China's marriage rate has collapsed to a historic low of 4.3 marriages per 1,000 people in 2024—less than half its 2013 peak (9.9‰). This places China alongside Japan and South Korea (4.2-4.3‰) but significantly below the U.S. (5.1‰), reflecting broader East Asian demographic trends. Three alarming patterns emerge:

The scale of first marriages has imploded. Between 2013 and 2022, registered marriages halved from 13.47 million to 6.84 million, with first-time marriages plummeting even faster—from 11.93 million to 5.26 million (a 55.9% drop).

Delayed marriages are shrinking the biological window for childbearing. The average age of first marriage for women has jumped from 24 in 2010 to 28.2 in 2023, with over 30% now marrying after 30—directly truncating peak fertility years (25-29).

Prohibitive economic barriers have turned marriage into a privilege. In major cities, saving for a marital home down payment now consumes 15-20 years of family income, while betrothal gifts (bride prices) often exceed 300-500% of annual household earnings—creating what amounts to a brutal financial gatekeeping system.

The fertility paradox: education gains vs. institutional roadblocks

With extramarital births accounting for less than 2% of births, China's marriage collapse directly strangles fertility—pushing the total fertility rate (TFR) to a catastrophic 1.0, far below both OECD averages (1.5) and Japan (1.2). This crisis stems not from changing individual preferences but from structural contradictions between progressive education and regressive social systems.

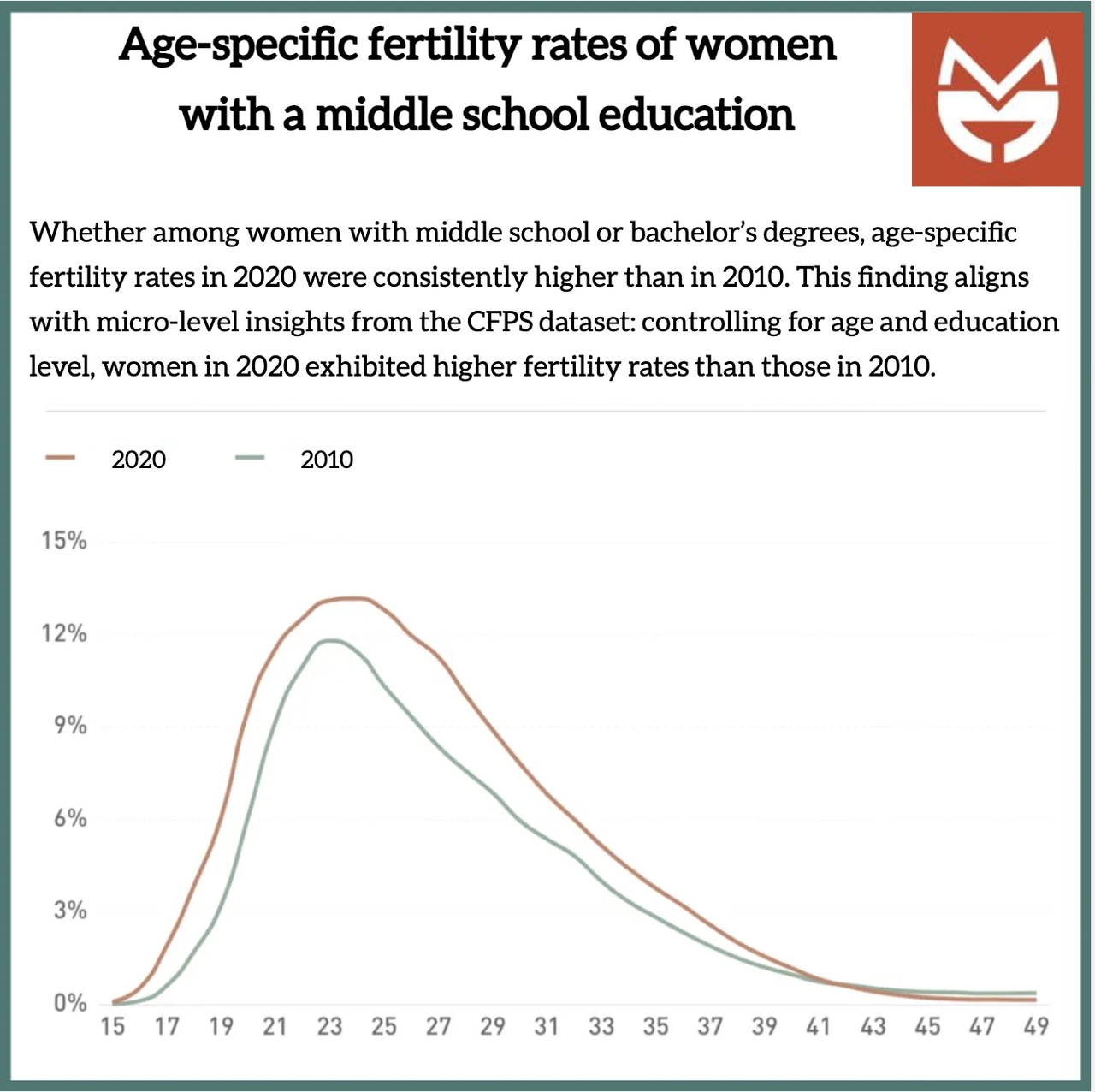

Higher education expansion has reshaped demographics: female tertiary enrollment rates exploded from 3.4% in 1990 to 59.6% in 2022, with each additional year of education reducing desired fertility by 0.26 children. Paradoxically, within each educational cohort, women's fertility intentions have actually increased since 2010, according to a research made by MetroData. The aggregate decline occurs because higher-education groups—who have fewer children—now dominate the population.

This education-driven fertility slump reflects systemic failures: career penalties for motherhood remain draconian.

Groundbreaking research reveals the severe professional tradeoffs Chinese women face when starting families. According to the 2023 Report on Chinese Women's Career Development, a rigorous 2021 study published in Population & Economics (a Peking University core journal) demonstrates that each child born to middle-income families reduces mothers' employment probability by 6.6% for the first child and an additional 9.3% for the second—even after controlling for education, region, and household characteristics. Notably, children show no statistically significant impact on fathers' employment prospects.

This "child penalty gradient" exposes systemic workplace discrimination where motherhood becomes a career liability. Unlike OECD countries where parental leave policies mitigate such losses (Sweden's 480-day paid leave reduces the motherhood wage gap to 4%), China's lack of institutional support forces women into an impossible choice—professional advancement or family formation.

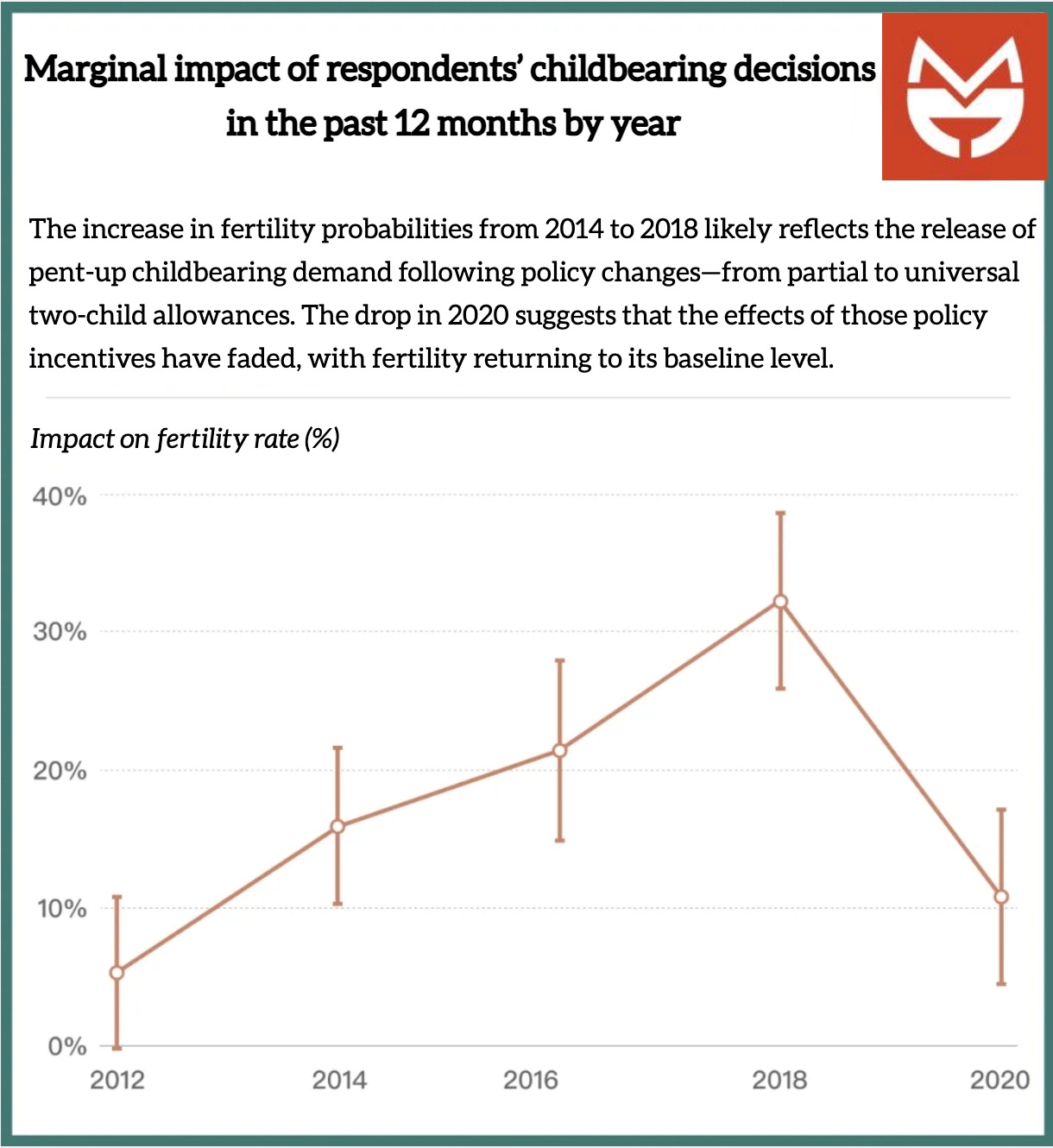

On the other hand, short-term policy incentives (from partial to universal two-child allowances) temporarily boosted fertility rates between 2014 and 2018 by releasing pent-up demand for childbearing. However, once this accumulated demand was exhausted, fertility rates after 2019 naturally declined to their baseline level. While still higher than in 2010, these post-2019 rates fell significantly below the 2016-2018 peak, objectively accelerating the recent decline in births.

Affected industries: Obstetrics, pediatrics, postpartum care centers, kindergartens, and consumer markets

When discussing the impacted industries, I’ve found that in most cases, the decline in newborn numbers is not the root cause of their struggles—rather, it serves as a catalyst, exposing and amplifying pre-existing structural weaknesses within these sectors.

"Saving maternity wards": the crisis from a fragile operating model

China's maternity care system is facing an unprecedented crisis. In 2021, the number of maternity hospitals nationwide decreased by 16 compared to 2019, while bed occupancy rates plummeted from 52.2% to 44.1%.

Professor Duan Tao's 2024 appeal to "save our maternity wards" at Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital sparked widespread public concern, exposing several systemic challenges:

First is the distorted economic model. Maternity service pricing remains at levels set during the midwife era of the 1950s, yet hospitals must maintain modern, 24/7 medical teams. This "high-cost, low-return" operation previously relied on overwhelming patient volume to break even. However, with national newborn numbers dropping below 9 million in 2023, the fatal flaw was exposed. Data from a Shanghai specialist hospital shows obstetricians' incomes have fallen 20-30%, with bonuses halved during low seasons.

More critically, there's a fundamental misalignment with policy direction. The CMI index and tier-4 surgery metrics in public hospital evaluations contradict maternity care's core mission of "prevention-first, safety-focused" care. As one tertiary hospital administrator admitted, "Achieving 98% natural delivery rates comes at the cost of bottom-tier performance evaluations."

Pediatrics mirrors this crisis.

As reported by Sanlian Life Weekly, At Beijing's China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Dr. Wang Zhixin, a 27-year veteran, observes: "No one wants to quit, but the brutal hours and low pay eventually force them out." Surviving here requires monk-like sacrifice—a reality Dr. Wang calls unsustainable. "When pay matches the work," she notes, "people will choose pediatrics willingly."

This testimony reveals systemic failures in valuing essential medical services, where vital pediatric care becomes a calling only the most selfless can afford to answer.

In the upcoming content, we will explore other industries impacted by birth rate decline, such as the closure trends in postpartum care centers and kindergartens, as well as the maternal and infant consumer market. Our analysis will cover their current situations and future prospects, including the latest strategy shifts by some listed companies (Yili, Goodbaby, Feihe Dairy, etc.).

We will also examine why I believe current fertility stimulation policies are overly simplistic and may prove insufficient, and I will propose potential improvements. Please note that this content is exclusively available to paid subscribers.