Songmont takes on LV for China's middle-class shoppers

China is entering the 'middle-aged women era' — What it means for consumer markets

Bernard Arnault, chairman of LVMH, stopped by two brand stores during his visit to China earlier this month. One was Laopu Gold, which has been eroding the market share of several international luxury jewelers, including those owned by LVMH. The other was Songmont (山下有松), a privately held leather and bag maker founded in 2013, still little known even among many Chinese consumers.

I won’t bore you with the story of Laopu, as I’ve already written a newsletter that comprehensively covered the brand and the analysis behind its rise. Today, I want to dive into Songmont, because it reflects far more about the Chinese consumer market than just the rise of another designer brand.

How domestic designer brands are on the rise

The prevailing narrative is that aspiring luxury and designer brands are struggling in China, as the middle class grapples with the twin shocks of a real estate downturn and slowing income and job growth.

Since Covid, “price-for-value” has become a defining theme in China’s consumer market. Luxury sales, after a strong start in 2023, have since diverged. At the top end, Hermès continues to outperform, while brands like Dior, Louis Vuitton, and Gucci—still heavily dependent on middle-class spending rather than the top 1% of ultra-affluent consumers—are losing momentum.

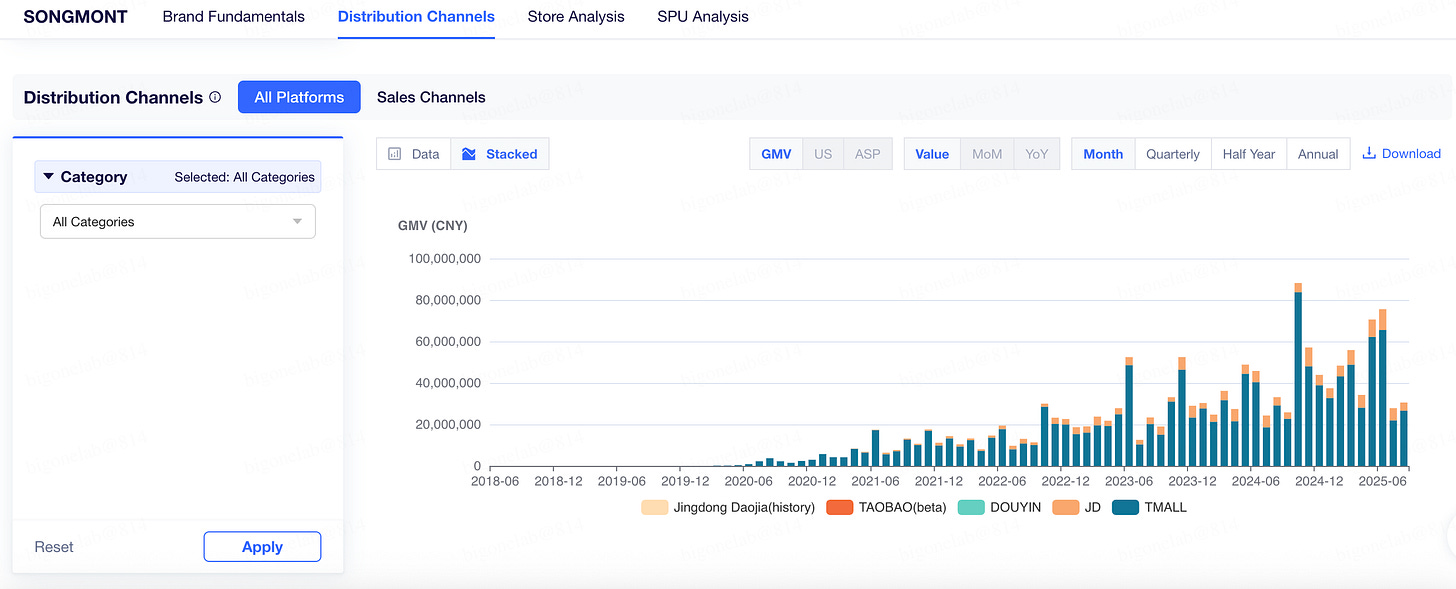

But as other aspiring and designer brands struggle, Songmont has emerged as a rising star. Priced at the entry-luxury level, most of its handbags retail between 1,000 and 3,000 RMB (140 - 421 USD)—placing it in direct competition with brands like Michael Kors and Coach.

Increasingly, young office workers in cities like Shanghai and Beijing—who once saved up for Louis Vuitton, Celine, or Fendi, often hunting for last-season styles in outlets or the secondary market—are turning to Songmont instead. Rather than spending tens of thousands of yuan on an LV bag, which could amount to more than half of their monthly salary, they see Songmont as a stylish yet far more affordable alternative, provided they are willing to let go of the “big-name logo” obsession.

The shift is visible in everyday retail scenes.

When I walked past a Songmont store in Sanlitun, Beijing, the other day—around 9 p.m. on a weekday evening—almost every other shop, from luxury boutiques to mid-tier designer brands, was empty. Songmont, however, was packed. Most of the customers were women in their late 20s or 30s, but I also noticed men in their 30s browsing. That struck me as unusual: in China, few men would spend several thousand yuan on a designer bag (unless they are already loyal luxury buyers). Otherwise, they usually skip branded bags altogether and stick to more affordable options. And this wasn’t just a one-off sighting. I’ve seen the same thing walking past Songmont stores in Shanghai and Nanjing—their shops consistently draw a lively crowd.

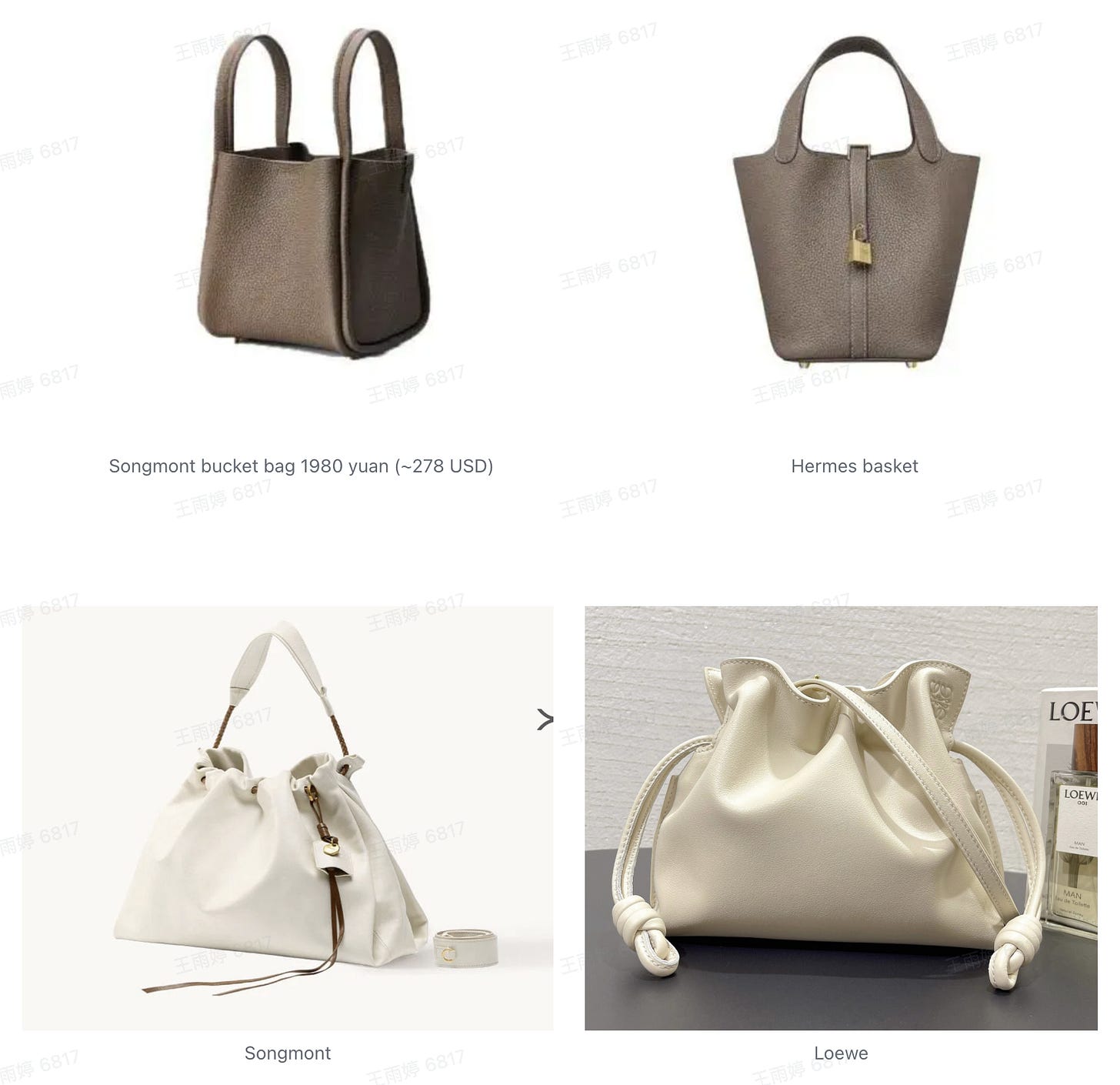

For Chinese urban consumers, Songmont strikes a sweet spot: the bags offer thoughtful design and solid quality—most are made of genuine leather, not on the level of Hermès, but certainly a step above the plastics and synthetic materials often used by fast-fashion designer labels. Many of Songmont’s bestsellers also incorporate elements of iconic international luxury houses, whether it’s signature colors or classic bag silhouettes. The result is that urban shoppers can signal refined taste and style at just a fraction of the price they would pay for an LV or Celine.

Songmont has also become a way to tap into the “quiet luxury” aesthetic that has surged in popularity in China over the past few years. As some netizens put it bluntly: “Carrying a Coach means you can probably only afford a Coach. Carrying a Songmont, on the other hand, suggests you might already have an LV, Hermès, or Chanel at home and are now looking for something more unique.”

The modern “classical Chinese style”, or the “China Chic”

Songmont’s success is not an isolated case. In fact, many domestic designers are building strong brands by leaning into what is often called the “modern classical Chinese style,” or simply “China chic.” Despite China’s long history, it was once rare to see luxury or designer products that reflect Chinese aesthetics. Affluent consumers were largely satisfied with paying for Western labels and design. But in recent years, a shift has taken place: more and more consumers are seeking to reconnect with China’s cultural heritage and identity.

In my article about Laopu, I noted that foreign luxury houses once filled the gap in China’s premium market simply because there were no real local alternatives. However, that doesn’t mean Chinese consumers naturally—or fully—resonate with the design or cultural messages of those Western brands.

This matters even more in the designer space, where storytelling, identity, and personal expression are core to the brand proposition. The rise of “China chic” has fueled a wave of homegrown labels that fuse traditional cultural elements with modern aesthetics. Songmont is part of this movement—but it is far from the only success story.

A common entrepreneurship path for these domestic fashion brands is to start locally—sometimes even purely online—to build a presence with minimal cost. Songmont, for example, launched a massively successful online business before moving into offline stores, usually selecting prime or tier‑1.5 locations so that its stores appear alongside brands like Gucci, Dior, Coach, and LV, often just one or two floors above them.

Other brands, such as HECO and Tangxindan, also rely heavily on online sales before expanding to physical stores in major cities like Beijing or Shanghai. They deliver a “modern Chinese style” that resonates with young consumers. While Chinese-inspired designs have long existed, many older designs are overly literal copies of traditional motifs, making many consumers feel that these designs belong to their grandma’s generation or are unsuitable for casual, everyday use. Emerging domestic designers are filling this gap by creating a modern “China Chic” that incorporates iconic traditional elements while blending seamlessly into contemporary life in an understated way.

These brands also place heavy emphasis on marketing and collaborate with celebrities to promote their products. As a result, consumers no longer feel that the brand is just “智商税”, or “IQ tax”—an internet slang term used by Chinese netizens to describe something that is overpriced and offers little value—but instead see it as something their idol admires, allowing them to showcase their own taste and values.

The celebrities involved are usually very well-known in China. Even though consumers fully understand that these items aren’t on the same luxury level as Hermès or LV, wearing these domestic bags or fashion pieces still serves as an effective form of social currency. It is far easier to pick one of these items than to navigate the many niche designer brands that have little to no presence on mainstream Chinese social media.

Songmont is no exception. It draws heavily on oriental aesthetics as its primary design inspiration, fusing elements of China’s ancient architectural and cultural heritage into its products. The Chinese name, Songmont—Song (松, pine) and Mont (山, mountain)—literally means “there are pines under the mountain,” evoking picturesque scenes that symbolize harmony with nature and reflect the essence of Oriental aesthetics.

For instance, the “Roof Bag” series draws its inspiration from the eaves of traditional Chinese architecture, referencing both its architectural structure, as well as the iconic jade color.

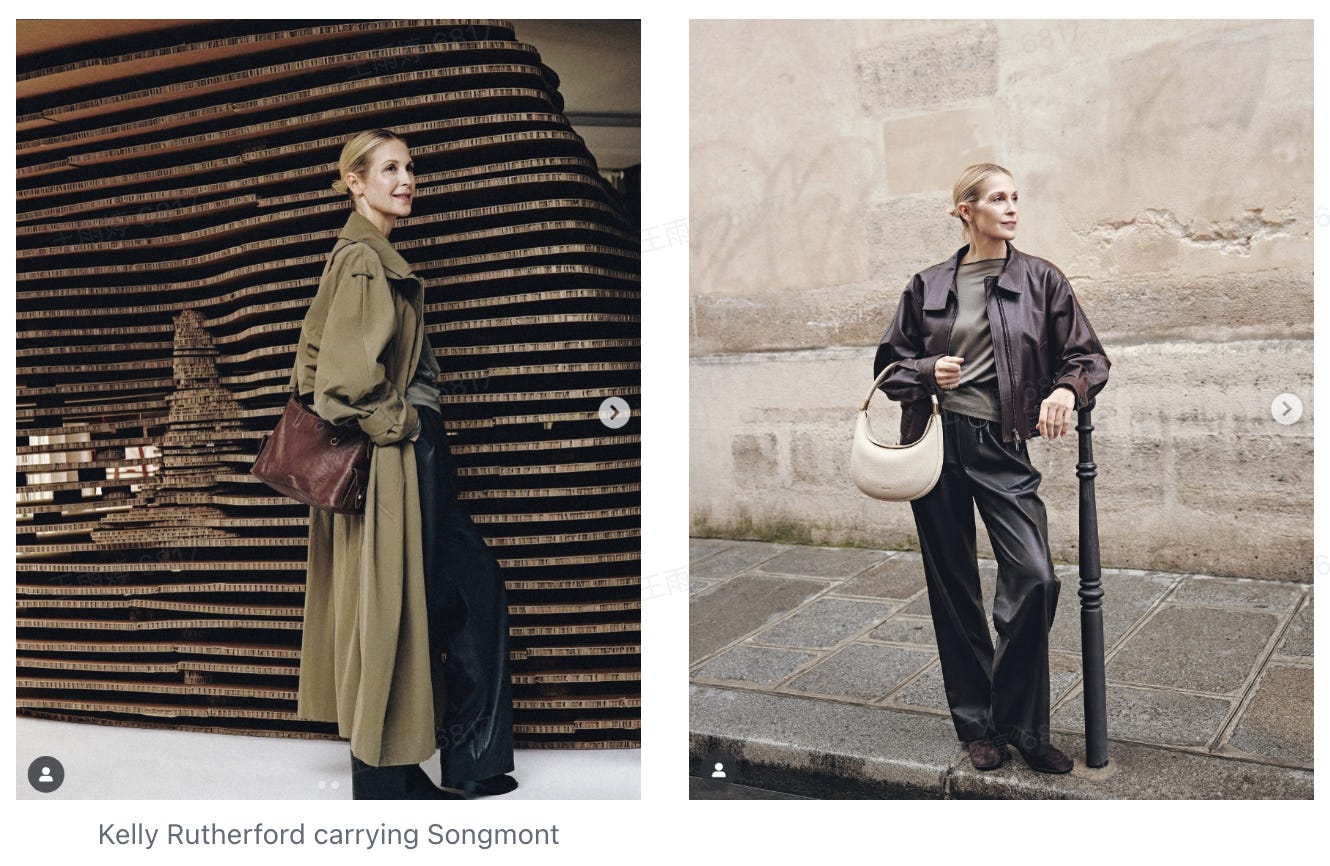

And Songmont has taken its marketing efforts to the next level. For instance, it has collaborated with many foreign KOLs and celebrities, including Kelly Rutherford, the actress who played Lily in the American show Gossip Girl. Her portrayal of upper-class, old-money elegance and timeless beauty left a lasting impression on many urban Chinese, especially those who grew up with exposure to foreign culture. Gossip Girl was once one of the most popular foreign shows among Chinese born in the 1990s, who are now in their 20s and 30s—the very demographic that forms Songmont’s core consumer base.

“中女时代” — The era of the middle-aged female

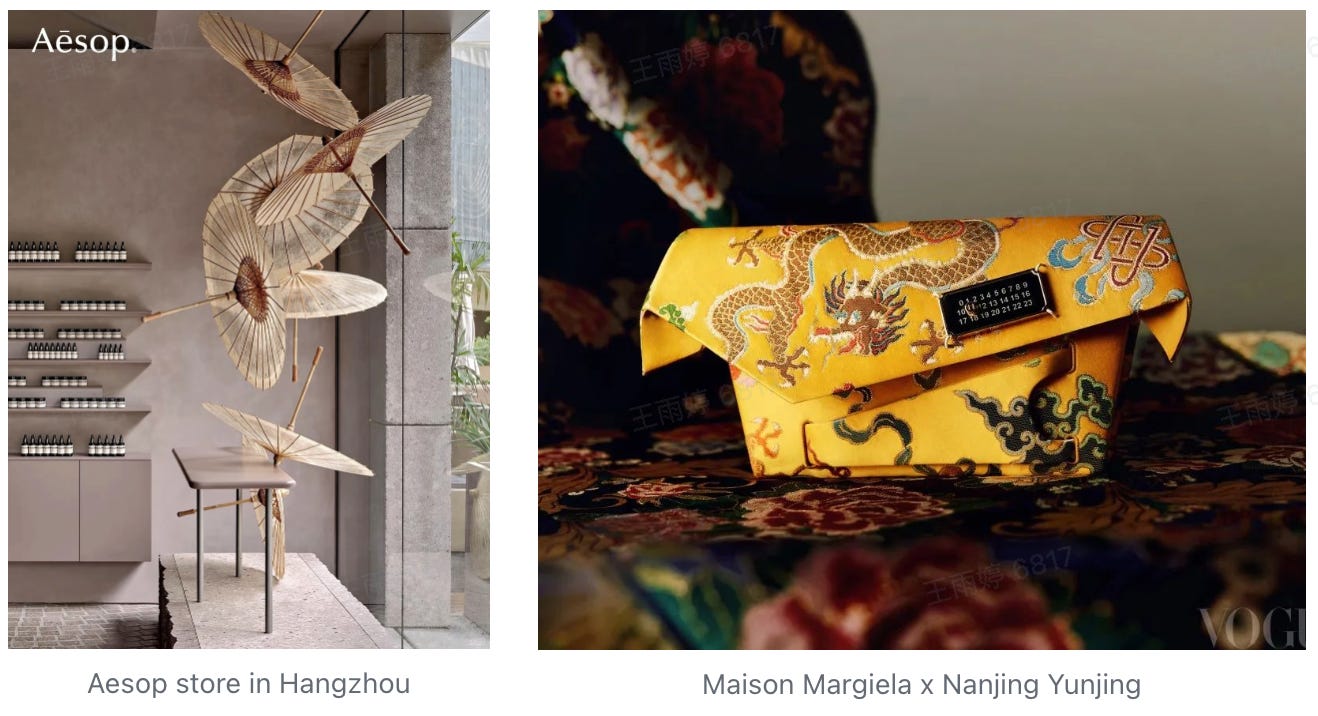

As the modern “China chic” vibe gains popularity, international brands are increasingly “forced” to integrate into Chinese consumers’ daily discourse. For example, Aesop incorporated the oiled-paper umbrella—an iconic cultural symbol in southern China—into its offline store interiors in Hangzhou; and Maison Margiela collaborated with Nanjing Yunjing, a century-old traditional Chinese silk brocade craftsmanship, for its bag designs.

Yet few brands have captured as much attention and resonance among consumers as domestic names like Songmont. Beyond symbolic similarities or direct references to cultural icons, consumers are increasingly seeking deeper connections: brand stories, values, and lifestyle statements that reflect their personal identity.