Space Race 2.0? 2026 is China’s "SpaceX Moment"

The much-anticipated IPO wave in China’s satellite and commercial space sector

In the final days of 2025, China quietly filed a bombshell with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). China submitted plans for two “super-constellations,” CTC-1 and CTC-2, totaling over 193,428 satellites [*].

For context, Elon Musk’s Starlink—the undisputed leader in low-Earth orbit (LEO) today—has a long-term target of around 42,000 satellites [*].

The scale alone signals that something fundamental has changed.

Historically, China’s space industry was a closed system dominated by state-owned “national champions,” primarily China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC). This model delivered strategic reliability, but it struggled to compete with SpaceX’s Starlink in the areas that now matter most: cost efficiency, iteration speed, and control over low-Earth orbit (LEO) resources, including military-grade communications.

Faced with Starlink’s overwhelming first-mover advantage, Chinese policymakers concluded that a purely state-led model was no longer sufficient. As a result, China’s policy direction has undergone a fundamental shift—from merely allowing private companies to participate, to actively supporting private firms as the main drivers of the commercial space sector.

In late 2025, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), together with the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE), revised the STAR Market (科创板, or China’s Nasdaq) listing rules. A dedicated IPO “green channel” was introduced for high-barrier, long-cycle hard-tech companies, particularly those focused on reusable rockets and space infrastructure [*].

The most important change: loss-making companies are now allowed to go public. As long as a firm demonstrates breakthroughs in core technologies—such as liquid rocket engine recovery—and aligns with national strategic priorities like China’s state-backed satellite constellations, traditional profitability requirements can be waived.

The impact was immediate.

On December 31, 2025—just days after the new rules took effect—LandSpace, one of China’s leading private rocket companies, had its STAR Market IPO application formally accepted [*]. The company is seeking to raise RMB 7.5 billion, at a reported valuation of RMB 75 billion. 2026 is shaping up to be a peak year for Pre-IPO monetization across China’s commercial space industry.

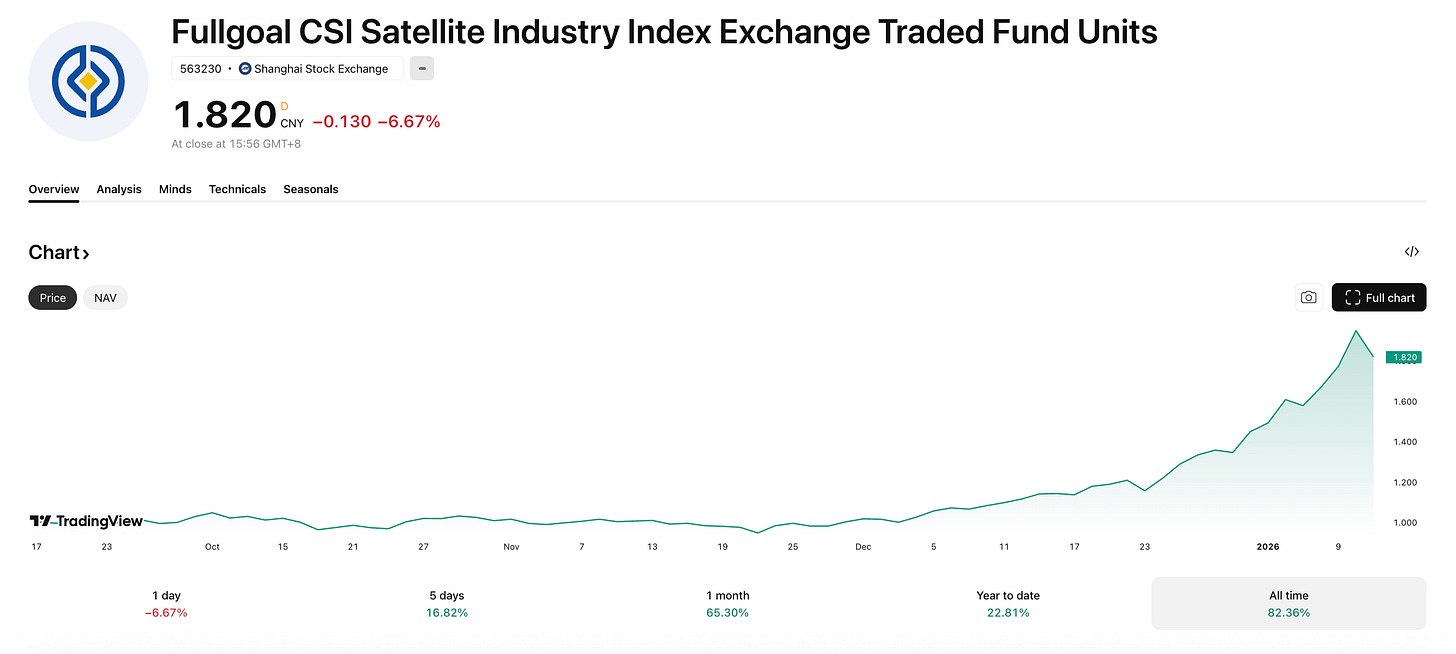

Secondary markets have already started to price this in. Beginning in December 2025, speculative enthusiasm surged, pushing several satellite and space-themed ETFs to nearly double from end-2025 levels (perhaps too much speculative betting at this point). Investor attention has shifted decisively from policy vision to execution—and to who will become China’s answer to SpaceX.

Why the Rush? The Race Against the ITU and the “Iron Curtain”

The sense of urgency within China’s orbital strategy is driven by a “red zone” countdown imposed by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Under the ITU’s “Use it or Lose it” rules, satellite constellations must hit strict deployment milestones to retain their claimed frequencies. Once a frequency is filed, the operator has exactly seven years to launch its first satellite and begin operations (Bringing Into Use, or BIU). But the clock doesn’t stop there: by year nine, 10% of the total constellation must be in orbit; by year twelve, 50%; and the entire fleet must be operational by year fourteen [*].

For China’s largest constellation, “GW” (Guowang), which filed for approximately 13,000 satellites in September 2020, the BIU deadline is September 2027. To avoid losing these precious spectrum rights, China must transition from ambition on paper to mass industrial delivery by 2026.

The Battle for Orbital Real Estate: Why 550km is the “Park Avenue” of Space

This regulatory pressure is compounded by Starlink’s hegemony. As of early 2026, Starlink has already launched over 9,422 satellites, and an additional 7,500 satellites were approved a few days ago, with 50% to be launched by 2028. Starlink has effectively occupied the prime orbital shells at 530 km and 550 km, and is now moving to compress its orbits down to 480 km.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) is generally categorized into three distinct layers: Ultra-Low Orbit (VLEO) below 400km, Core LEO between 400km and 600km, and High LEO above 1,000km.

The narrow bands at 530km and 550km are considered the “prime real estate” of the sky. At these specific altitudes, the physics of communication and safety reach a perfect equilibrium. These orbits are high enough to minimize atmospheric drag, allowing satellites to stay aloft for years without excessive fuel consumption, yet low enough to keep signal latency at a crisp 20–40 milliseconds—ideal for high-speed trading and gaming. Critically, these layers also benefit from “passive safety”: if a satellite fails here, the thin atmosphere will naturally pull it down to incinerate within a few years, preventing a permanent buildup of space junk[*].

Starlink has effectively “colonized” these core shells, forcing competitors to either climb higher (thus more latency) or dive deeper into the more challenging VLEO zones (difficult because intense atmospheric drag requires constant orbital maneuvers and specialized aerodynamic designs to prevent satellites from prematurely re-entering the atmosphere).

But if China does not scale up mass production and launch by 2026, it will be orbitally blocked by Starlink’s sheer physical presence.

Is This Space Race 2.0?

At first glance, the echoes of the 1960s are unmistakable. Once again, two superpowers are vying for the “ultimate high ground” to secure not just national pride, but undisputed strategic dominance. In the past, whoever reached space first demonstrated the superiority of their system and their intercontinental missile capabilities. Today, whoever controls low-Earth orbit satellite networks controls a “god’s-eye view” of global communications and modern military command.

But this time, there are three key differences.

First: orbit and spectrum as non-substitutable strategic resources. Orbital slots and frequencies are physically scarce. If China does not file and launch now, once Musk’s 42,000 satellites are fully deployed, there may simply be no room left for latecomers.

Second: the primary driver is also commercial, not just political. The Apollo program was never profitable, but satellite connectivity today is a trillion-dollar market—powering 6G, autonomous driving, and global broadband. For example, China Mobile (0941.HK) has also applied for 2,520 satellite launches, not because a telecom operator suddenly developed ambitions for Mars, but because it wants to place its base stations in orbit—selling 24/7 connectivity and controlling the pricing and data flows of direct-to-device communications.

Third: the players have fundamentally changed. Space Race 1.0 was a pure state-to-state competition—NASA versus the Soviet space program. This time, it is a hybrid model: SpaceX as a private-sector champion versus China’s state-backed giants operating alongside a growing ecosystem of private companies.

How China Advances Its Orbital Strategy

To compete with Starlink’s established dominance, China has moved away from a pure “National Team” model. Instead, it has adopted a more distributed approach, spreading the burden of deployment across central authorities, regional governments, and private companies.

You can also get free access by sharing us. If you find our content helpful, please consider getting a paid subscription to access the exclusive benefits for Baiguan paying subscribers.