Why China is building the world's largest hydropower station in Tibet

And what it means for China's economic and energy future

"The project of a century"

On July 19, 2025, Chinese Premier Li Qiang stood in the remote southeastern Tibetan city of Nyingchi and announced the official commencement of the Medog hydropower station—what he termed a "project of the century".

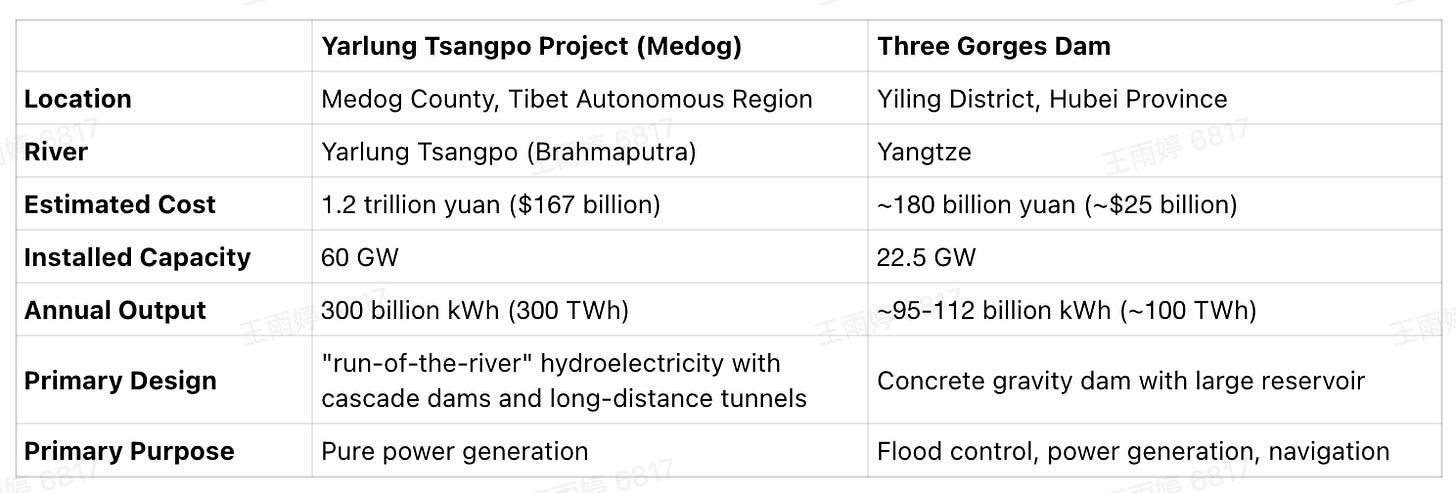

The mega project is a hydropower station on the lower reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, a plan of such breathtaking scale that it redefines the very concept of a mega-project. With a projected investment of 1.2 trillion yuan (approximately $167-170 billion) and a planned annual electricity output of 300 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh), the facility is designed to generate nearly three times the power of the iconic Three Gorges Dam, China's previous "project of the century".

Its output alone would be enough to power the entire United Kingdom [*(2023 statistics)] and is equivalent to 20% of China's total residential electricity consumption in 2024 [*], enough for 300 to 400 million people.

The economic benefits of the hydropower project far exceed those of typical power generation projects. Industry experts predict that the construction will directly create 100,000 to 200,000 jobs—three times the number created by the Three Gorges Project. Once completed, the project is expected to generate approximately 20 billion yuan in annual fiscal revenue for Tibet, accounting for about two-thirds of its projected fiscal revenue for 2024 [*].

The timing of this monumental announcement is as significant as its scale. It comes at a time when China’s economic growth is weighed down by a struggling property sector and persistent deflationary pressures, following decades of meteoric expansion. Against this backdrop of economic anxiety, the decision to launch a multi-decade, multi-billion-dollar project in one of the most remote and geologically challenging regions on Earth seems, at first glance, counterintuitive.

It raises a central question: why now?

Is this infrastructure push a bid to stimulate the economy, a display of China’s technological and political might, or a strategic effort by Beijing to rally national sentiment by showcasing the state’s immense capacity to act?

The century-old dream realized: A century of China's hydropower ambitions

To say that this project represents more than just a strategic pivot would not be a mistake. When the Three Gorges Dam—the last so-called “project of the century”—was launched, it coincided with the beginning of China’s decades-long economic boom.

For many in China, the Three Gorges Dam's construction period, from 1994 to its completion in 2006, is inextricably linked with the country's decade of explosive economic "take-off." It became more than an engineering marvel; it became a potent symbol of national pride and a harbinger of an era of unprecedented prosperity. This powerful association has created a form of national reminiscence, a collective hope that the Yarlung Tsangpo project, being even larger and more ambitious, could similarly kickstart a new "super-cycle" of growth, especially when the economy is slowing after meteoric expansion in past decades.

The ambition to harness China’s great rivers is far from new. It is a vision deeply embedded in the country’s modern DNA—a recurring dream of national rejuvenation. The ideological lineage of the Yarlung Tsangpo project stretches back over a century, to the very founder of modern China: Sun Yat-sen. In his 1920 treatise The International Development of China (《实业计划》), Sun envisioned vast hydropower projects on the Yangtze River—what would later become the iconic Three Gorges Dam—as a pillar of his strategy to modernize the nation through flood control and electrification.

Sun’s grand industrial blueprint included three core strategies:

Building a national railway network, including lines through high-altitude regions—an idea that eventually materialized as the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, now the world’s highest railway, officially inaugurated in 2006;

Coordinating the development of China’s water resources, including what would later become the Three Gorges Dam;

Integrating the economies of the frontier regions—a goal that later became massive state-led campaigns, such as the Western Development Strategy, aimed at reducing economic disparities between China’s prosperous coastal areas and its inland and western regions.

In 2005, the idea took a particularly controversial yet provocative shape with the publication of the book Tibet's Water Will Save China. Authored by Li Ling, a former People's Liberation Army officer, the book proposed a radical engineering scheme to divert vast quantities of water from the Yarlung Tsangpo and other major rivers to the arid, water-starved plains of northern China.

Although the book is mostly a conceptual vision and an eloquent narrative by the author—and was never officially accepted by Beijing (and the vision differs completely from the current hydropower project)—the book’s audacious idea nevertheless struck a chord with many older Chinese generations and reinforces a view that remains influential today: that taming China’s rivers is inseparable from the quest to build a strong, modern state.

Engineering on the roof of the world: technical details of the project

China’s hydropower ambitions have evolved over the decades, with a series of ambitious projects—each building on the experience of its predecessors.

From the Gezhouba Dam (1970 - 1988) on the Yangtze to the massive Three Gorges Dam (1994-2003), and more recently to high-altitude stations like the Lianghekou Dam on the Yalong River (2014-2021)—which remains the highest-altitude hydropower facility to date, with an average dam elevation of around 3,000 meters—China has steadily built its technical expertise required to master its great rivers.

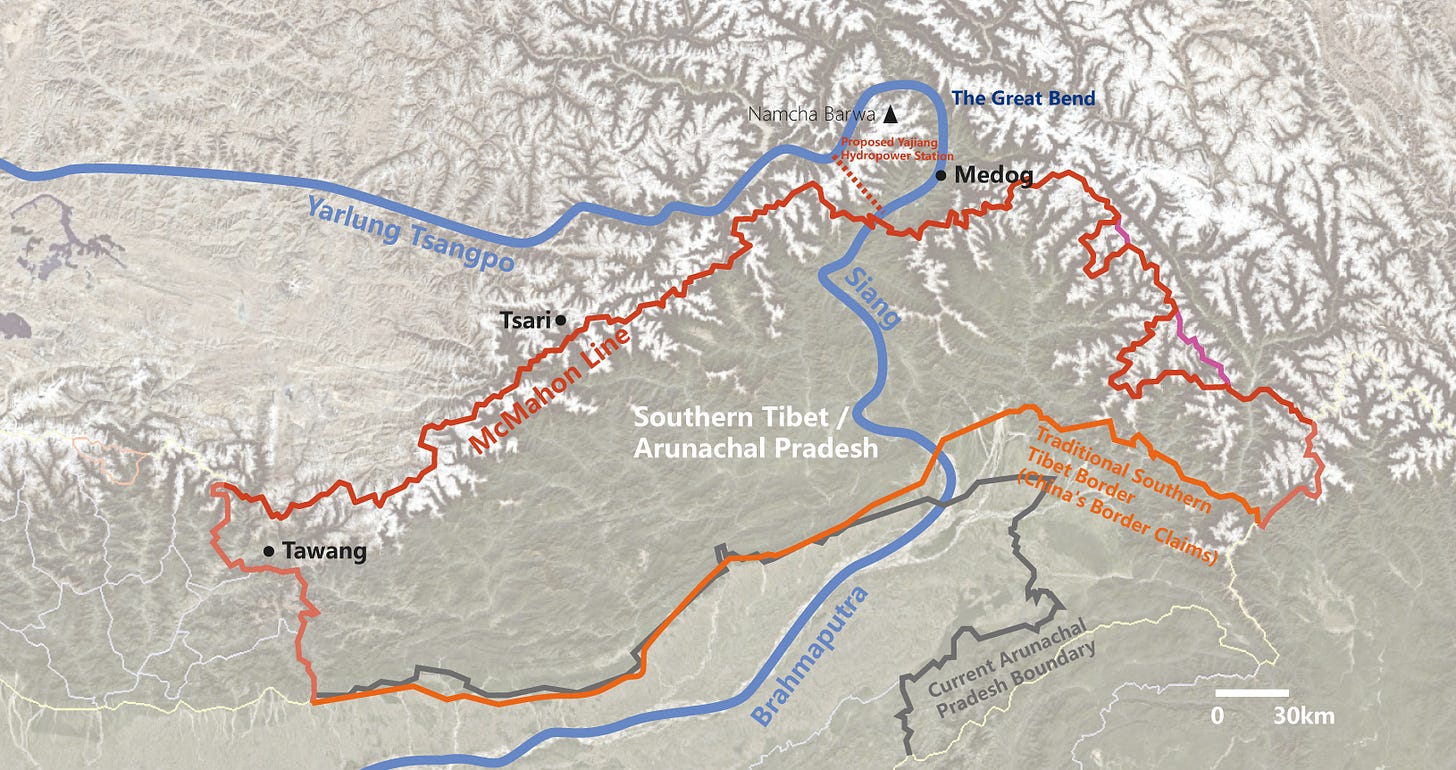

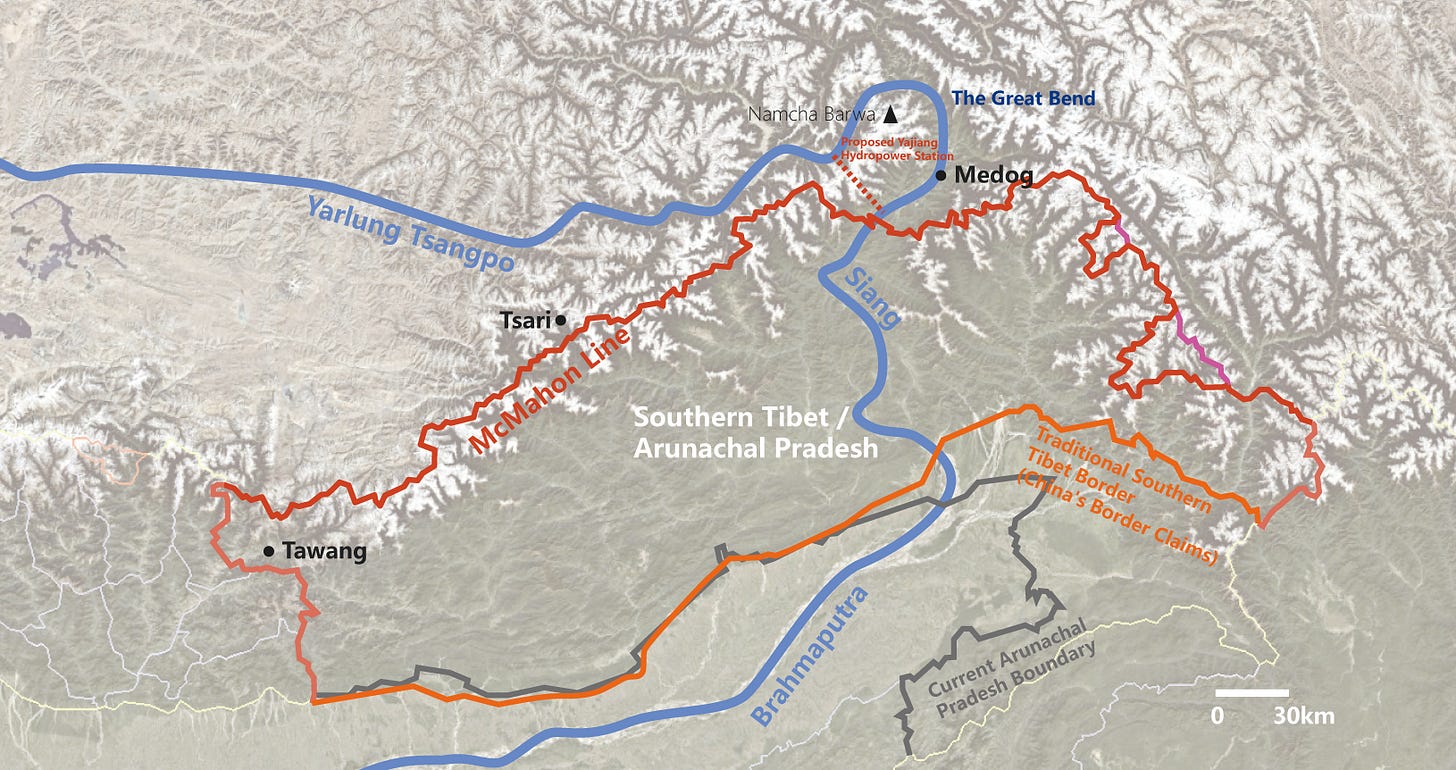

The Yarlung Tsangpo project marks the boldest chapter yet. It is located in Medog County, a remote corner of southeastern Tibet, at a dramatic geographical feature known as the “Great Bend” of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. Here, after flowing eastward across the Tibetan Plateau, the river makes a hairpin turn around the sacred Mount Namcha Barwa and plunges south toward India. In just 50 kilometers (31 miles), the river drops between 2,000 and 2,350 meters (over 6,500 feet) [*], through the world’s deepest canyon—three times deeper than the Grand Canyon in the United States.

It is this staggering vertical drop that has long been viewed by engineers as the single most promising site for hydropower generation on Earth, with a water energy density estimated to be seven times that of the Three Gorges [*].

To exploit the potential of the "Great Bend," China is employing the "run-of-the-river" design, or, figuratively speaking, the "cut-the-bend" approach. Instead of constructing a single massive dam with a vast reservoir—which would be impractical and even more hazardous in this terrain—the project will consist of a series of five smaller "cascade" hydropower stations. These dams will divert a portion of the river's powerful flow into a network of four enormous tunnels, each stretching approximately 20 kilometers (12.5 miles) and bored directly through the Himalayan mountains [*].

This "run-of-the-river" approach, which utilizes advanced dam-less diversion technology, means water is not consumed but rather borrowed with a resource utilization rate of up to 85% (*). It plunges down these tunnels, gaining immense velocity, to spin turbines located at a much lower elevation at the bottom of the canyon. After generating power, the water is discharged back into the river just before it crosses the Line of Actual Control into India. This design allows China to harness the massive potential energy from the 2,000-meter elevation drop while minimizing the size of the required reservoirs.

So why has China waited until 2025 to commence this project?

Because building in this location presents engineering and environmental challenges on a scale previously unimaginable—not just for China, but for any country in the world.

For instance, the engineering challenges require technical capabilities that China has only developed in recent decades.

Beyond basic infrastructure like building roads and bridges, two key technologies have made this project feasible:

The first is tunnel boring machines (TBM)—used to dig long tunnels through mountains, similar to how a pangolin burrows through soil. These machines were once monopolized by German manufacturers and were prohibitively expensive. But after China localized their production, they became widely available and cost-effective.

In the early planning stages of the Medog hydropower station, several construction proposals were considered. Now, only one remains viable: a “run-of-the-river” approach, which involves digging a tunnel over 30 kilometers long to connect both ends of the river’s U-shaped bend, using the more than 2,000-meter drop in elevation to generate electricity. Such an idea would have been unthinkable in the past—but with TBMs, it has become a realistic option.

In fact, there’s already a prototype for this kind of construction: the Jinping II Hydropower Station on the Yalong River. Its surrounding terrain is nearly identical to that of the Medog section. There, engineers cut through both ends of a similar U-shaped bend, building four water diversion tunnels—each 17 kilometers long. The station has been operational for six years and has proven stable.

With this prior experience as a foundation, taking on the challenge of the Himalayas no longer seems so daunting.

The second breakthrough is ultra-high-voltage (UHV) power transmission. Tibet is vast and sparsely populated, and local demand is far below the project's potential output. Most of the electricity will need to be transmitted to major power-consuming provinces in the east—or exported to Southeast Asia. The only viable solution for such long-distance transmission is UHV, one of the few technologies in which China is globally recognized as a clear leader. Years of experience from the “West-to-East Power Transmission” program have proven that UHV is both mature and reliable.

Translated from 雅江水电工程背后的大国博弈 The Great Power Struggle Behind the Yarlung Tsangpo Hydropower Project

The project site sits near the Indus-Yarlung Suture Zone, the tectonic collision point where the Indian plate forces its way under the Eurasian plate. This is one of the most seismically active areas in the world. To counter this, engineers have developed advanced techniques and systems designed to help the tunnels resist earthquakes up to magnitude 8.5.

The canyon is not just a geological marvel but also a globally significant biodiversity hotspot. The unique geography, combining a massive change in elevation with wet monsoon air from the south, has created a range of ecosystems from tropical rainforests to alpine meadows, hosting rare species like the snow leopard and some of Asia's tallest and oldest trees. This makes it essential for the design and construction activities to be precisely planned and rigorously tested to minimize the threat to this fragile and irreplaceable environment.

Also, the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon is one of the most inaccessible places on Earth. Until the completion of the Paizhen-Medog Highway in 2022, the area lacked reliable road access and a power supply, making the logistics of transporting millions of tonnes of materials like steel and an estimated 40 million tons of cement a monumental undertaking.

The resulting power output is staggering. The project is designed with an installed capacity of 60 to 70 gigawatts, producing 300 billion kWh of electricity annually. This is enough energy to meet the needs of nearly 300 million people, making it by far the most powerful hydroelectric facility on Earth.

The initial feasibility studies for the Yarlung Tsangpo project began in the 1950s but were paused due to a major earthquake. It wasn't until 1982 that a joint expedition conducted the first field survey of the "run-of-the-river" concept. A systematic survey in the 1990s confirmed that 90% of the river's entire hydropower potential was concentrated in the Great Bend. However, due to technical and logistical limitations, the project was not pursued further at the time.

In 2005, a formal construction plan was proposed, and in 2020, the project was officially included in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan. Key logistical hurdles were overcome with the completion of the Paizhen-Medog Highway in 2022, and the project received final approval from the State Council in 2024.

After a long and cautious journey, the Yarlung Tsangpo project is finally becoming a reality.

The sheer ambition of the Yarlung Tsangpo project is best understood when compared to its famous predecessor, the Three Gorges Dam.

This comparison makes clear that while the Three Gorges Dam was a monumental feat of civil engineering focused on taming a river, the Yarlung Tsangpo project is a more technologically complex endeavor.

It also reflects the level of strategic foresight and long-term, forward-looking planning—planning that transcends economic fluctuations and political cycles—required to execute industrial and infrastructure development on the scale China is pursuing today.

The geopolitics

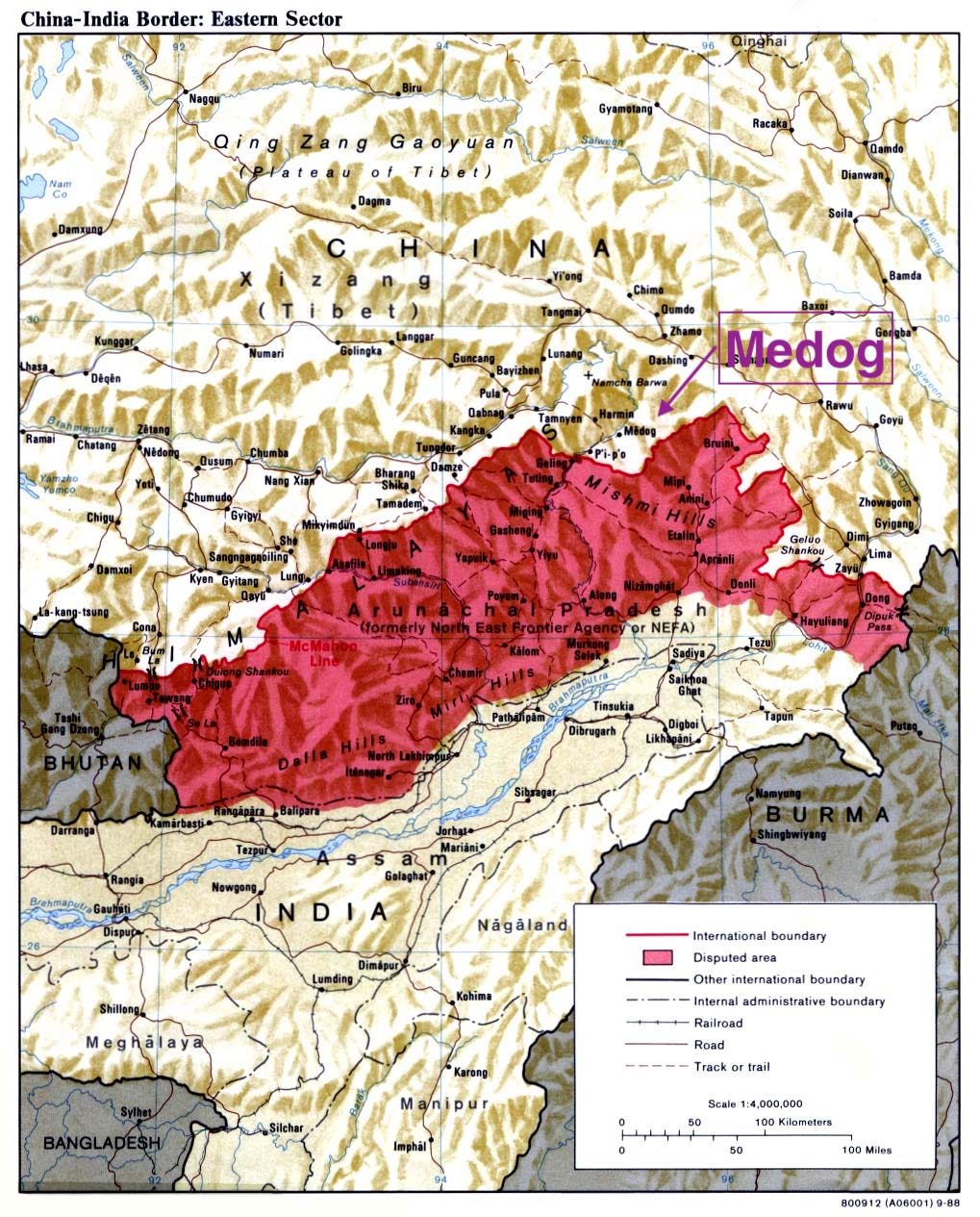

A major hydropower project is being built in Medog County, the last county in Tibet before the Yarlung Tsangpo River crosses the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and enters the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. The Yarlung Tsangpo River is called the Brahmaputra after it enters India.

This is not just any border: China claims the entirety of Arunachal Pradesh as “South Tibet,” rejecting the colonial-era McMahon Line that currently serves as the de facto boundary. The project's location, just a stone's throw from a disputed border, has inevitably placed it at the center of one of Asia's most sensitive geopolitical rivalries.

For India, the project is not an engineering feat but a source of deep strategic anxiety, raising fears of water security due to China's construction of the Medog Hydropower Station, which flows downstream into Bangladesh as the Jamuna River.

This has fueled intense alarm downstream. Indian officials fear that control over the river's headwaters gives Beijing a powerful tool of coercion. The Chief Minister of Arunachal Pradesh has publicly described the project as a "ticking water bomb," warning that China could manipulate river flows. “Suppose the dam is built and they suddenly release water—our entire Siang belt would be destroyed,” he said [*].

However, a closer look at the region’s hydrology and China’s broader strategy reveals a more complex reality.

In fact, China does not control the majority of the Brahmaputra’s water.

The upstream Tibetan Plateau is a high-altitude cold desert with relatively low precipitation. The river only transforms into the mighty, flood-prone Brahmaputra after entering India, where it is fed by torrential monsoon rains in the Eastern Himalayas and powerful tributaries such as the Lohit and Dibang. Snow and glacial melt from Tibet contribute only a small fraction of the river’s total volume.

Scientific studies and hydrological data consistently show that the bulk of the river’s annual flow—around 65–70%—is generated within India’s borders. China’s upstream contribution (mainly glacial melt in Tibet) accounts for only about 25% [*].

This hydrological profile fundamentally limits China’s ability to “turn off the tap” and cause droughts in India. Moreover, the project’s "run-of-the-river" design ensures that water is not consumed but merely diverted to generate electricity before being returned to the river, meaning the downstream volume will not be significantly affected.

Ultimately, the geopolitical conflict is less about the physical quantity of water and more about the "institutional vacuum" in which this project is being built.

By constructing a strategic national asset of this magnitude in the heart of contested territory, Beijing is embedding its sovereignty claim in billions of tons of concrete and steel—fundamentally altering the strategic landscape. This move is also likely to bring population growth and economic development (including surplus electricity exports to neighboring countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, and even Northeast India) to a sparsely populated frontier, helping establish a strategic balance with the more populous side.

A jolt to the equity market

The announcement of the Yarlung Tsangpo project sent immediate ripples through China’s A-share market. In an economy starved of structural growth drivers like real estate once was, the state’s endorsement of a 1.2 trillion yuan undertaking acted as a powerful catalyst, igniting a rally in infrastructure-related stocks. Sectors like cement and engineering machinery gained over 8% in just one day on July 21, the first trading day after project commencement.

The market quickly identified key beneficiaries. State-owned giants such as Power Construction Corporation of China and China Energy Engineering Corporation, the designated primary contractors, saw their shares surge following the announcement of project commencement.

The rally also lifted a wide range of “hydropower concept stocks,” from heavy machinery to civil explosives suppliers. For instance, in the cement sector alone, all 21 A-share-listed cement companies saw their stock prices rise by over 8%, with 19 of them hitting the daily limit-up — and, of course, not all of them secured contracts.

On July 21, over 70% of A-share stocks closed higher. In the Hong Kong stock market, the power grid equipment sector rose by more than 40%.

The market smells speculative fervor, but sophisticated investors should understand that the catalyst has already been priced in by now.

The strategic imperative: powering China's future

The true implications of the project transcend the short-term equity market craze. Economic stimulus, while a welcome side effect, is far from its primary objective.