China's discourse: China's "Father of AI" blacklisted; Nobel Prize laureate Mo Yan sued for "insulting the martyrs"; Yuhui Dong's "underwear shame" PR crisis

3 essential discourses to gauge China's latest social temperature

Gain insight into the latest social and economic developments in China through our curated selection of three pivotal discourses. These discussions have been chosen for their relevance and wide-ranging impact, showcasing significant structural shifts currently unfolding in China - some being controversial topics that resonate deeply in the community. Despite their importance, these conversations often remain underrepresented in mainstream Western media.

Today, we spotlight three public events that have sparked discussions among investors, consumers, and the general public: the downfall of the so-called "father" of China's AI, a lawsuit against Mo Yan for allegedly insulting martyrs, and accusations of Yuhui Dong's alleged gender discriminatory comments.

“Father” of China’s AI got blacklisted

Recently, a meme captioned "中美两大AI巨头 two AI giants America vs China" went viral on the internet. The meme, which juxtaposes Sam Altman and Yizhou Li - the latter SARCASTICALLY referred to as the "father of China's AI" by Chinese netizens - sparked significant controversy on China's internet.

Sora's debut on February 16 sparked considerable discussion among Chinese AI professionals, entrepreneurs, and the general public. Many expressed concerns on social media about the intensification of AI competition. Amidst the hype, Yizhou Li (李一舟) emerged as a notable figure. However, he was not recognized for any technological breakthroughs but rather for the enormous profit he made from selling AI courses.

Yizhou Li, who holds a Ph.D. from Tsinghua University's Academy of Arts & Design - one of China's most prestigious universities, markets himself as a "Tsinghua Ph.D" and founder of three technology companies. He has taught millions how to leverage AI for traffic and sales. Li became a viral sensation with his online videos, leading to the sale of approximately 250,000 AI courses in 2023, generating around 50 million RMB in revenue.

Despite his successful sales, Li faced criticism for offering low-quality courses and for allegedly repackaging ChatGPT under his own brand, "一舟智能 Yi Zhou Intelligence." There were also questions about his non-STEM background from Tsinghua University. Many netizens claimed that Li knew nothing about artificial intelligence, yet was profiting from selling courses.

The controversy escalated when, on February 22, all of Li's AI courses were removed from the internet, and his video account was suspended. The situation also attracted attention from legal experts and mainstream media, including China Central Television (CCTV), raising additional issues such as false advertising, consumer fraud, and copyright infringement.

The incident highlighted a broader discourse on the quality and authenticity of AI education and applications in China. Critics accused Li of "cutting leeks割韭菜" (a Chinese slang term for exploiting consumers), while supporters credited him for making AI concepts accessible to a wider audience.

Journalists at South Reviews spent some time watching Li's AI courses and found that the content mainly focuses on the introduction to AI2.0, ChatGPT, Notion AI, and stable diffusion. Li's courses aim to attract middle-aged people from 30-50. Unlike other online resources that are more technical, Li's courses focus on daily scenarios such as using AI to polish resumes, finding jobs, mock interviews, starting part-time businesses, and tutoring kids. One of Li's fans, a 35-year-old from Anhui province, commented upon seeing the meme picture featuring Li and Altman:

"Today is the first time I've heard of Altman. Before this, I only knew about Yizhou Li. His classes are quite good." [South Reviews]

The controversy sparked mixed feelings about AI's rapid growth and commercialization, prompting many to reflect on the real gap between China's AI industry and global leaders like OpenAI. As South reviews reported:

Many Chinese AI investors have revealed that when investing in Chinese AI companies, they focus on investing in scientists and value the academic background of the founding team.

[but] These tech-savvy masters also have another "defect": they are less eloquent and prefer to keep a low profile. Obviously, compared to OpenAI, China has not yet produced an AI "politician" like Sam Altman, who is skilled in commercialization and public speaking, and can effortlessly attend various political occasions and hearings.

How to understand the event: The controversies surrounding Li are just a snapshot of the "AI gold rush" happening in China's market. For the average Chinese internet user, the anxiety is real, and there is immense curiosity about AI advancements and their potential for commercial success. We discussed this trend in our newsletter in July last year, reporting on the surge of GPT-related education materials in China and the use of AI by Chinese merchants to create digital avatars for their e-commerce platforms.

As many Chinese netizens jokingly stated:

The first group to get rich from AI turned out to be those selling courses.

Nobel Prize laureate Mo Yan was sued for "insulting the martyrs and beautifying the invading Japanese army"

Mo Yan (莫言) is a renowned Chinese writer, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2012, making him the first Chinese national to receive the Nobel Prize in this category. His real name is Guan Moye (管谟业), and he adopted the pen name Mo Yan, which means "don't speak" in Chinese. Born on February 17, 1955, in Gaomi, Shandong Province, China, Mo Yan grew up during the Cultural Revolution, a period that deeply influenced much of his work.

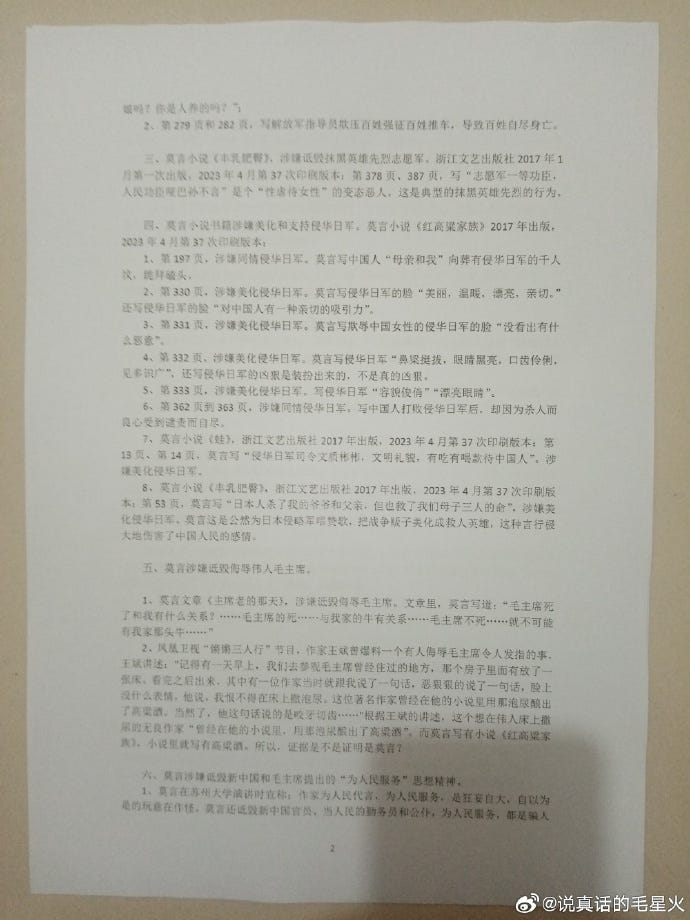

On February 22, a Weibo blogger named The truth-teller Mao Xinghuo 说真话的毛星火 with 219,000 followers sued Mo Yan. He claimed that Mo Yan had insulted the martyrs and beautified the invading Japanese army. The blogger claimed that there were significant issues in his novels "Red Sorghum," "Big Breasts & Wide Hips," and "Frog," and pointed out 26 specific issues, which amounted to more than 40 pages when printed.

Blogger Mao Xinghuo stated that Mo Yan was a "traitor," hurting the feelings of the Chinese people. He sued Mo Yan, asking the court to:

1: Remove all problematic books by Mo Yan.

2: Order Mo Yan to apologize to the martyrs and the people of the whole country.

3: Order Mo Yan to compensate each person one yuan for reputation loss, a total of 1.5 billion RMB.

Mao Xinghuo's lawsuit document, posted on his own Weibo account, summarized the evidence against Mo Yan for allegedly "smearing heroic martyrs and violating the Martyrs Protection Law". Citing an example on his lawsuit paper:

On page 330, Mo Yan is accused of "beautifying the invading Japanese army". Mao alleges that Mo Yan depicted the faces of the Japanese invaders as "beautiful, warm, pretty, and friendly", and wrote that their faces had "a kind of friendly attraction to the Chinese people."

This has sparked a significant online debate, reflecting broader concerns about internet nationalism, political correctness, and the impact of social media on public discourse and societal harmony in China.

Many warned against Mao Xinghuo's behavior, with some calling him a "jumping clown" and accusing him of preying on others to monetize internet traffic by creating a sensation. Hu Xijin, a Chinese opinion leader and former editor-in-chief of Global Times, stated that "Behind the farce of suing Mo Yan, the danger of populism is heating up."

Notably, the debate is not one-sided. An online poll conducted by Mao Xinghuo himself reveals that nearly ten thousand people support the lawsuit against Mo Yan (nearly 80% in the poll), with approximately 15% voting against it.

How to understand the event: The lawsuit against Mo Yan is one example of several recent debates sparked by overly populist content on the internet. In fact, there's been an emergence of "anti-populism censorship" in China, as Baiguan’s Robert Wu observed in his personal newsletter, Lost in Translation. This targets populist content that could damage business and social confidence, despite the fact that such populist expressions are often tolerated because they align with patriotic or societal norms.

Furthermore, these controversial social events reveal the complexity of understanding today's China. Last month, Robert applied a “Duo-China model” to understand the division between what he called the “Liberalist China” and the “Traditionalist China”.

Liberalist China consists of well-educated, cosmopolitan, younger, and economically better-off individuals who are conscious of their rights and articulate in expressing them. They represent a small percentage of the population (estimated at 5%-15%), yet they are very vocal and visible, especially in public discourse and on international platforms.

Traditionalist China makes up the majority, characterized by lower income, less education, and a more traditional lifestyle. This group is less vocal and less visible in public and international discussions but constitutes the bulk of the population.

The disparity between these groups is highlighted by differences in income and lifestyle, and has contributed to many controversial debates, such as the lawsuit against Mo Yan. If you are interested in delving deeper, I recommend reading Robert's personal newsletter, which provides an excellent overview:

Yuhui Dong's "underwear shame" PR crisis

Yuhui Dong, the individual who spearheaded New Oriental Education (NYSE:EDU)'s transition into e-commerce after the regulatory changes in 2021, ran into big troubles again just a few months after his epic battle with New Oriental’s management was settled.

During a recent live stream, several pieces of women's underwear were listed for sale. Dong, typically an eloquent presenter, was noticeably reserved and quiet throughout the stream. He simply commented, "anyone who wants it can place an order," a departure from his usual selling style.

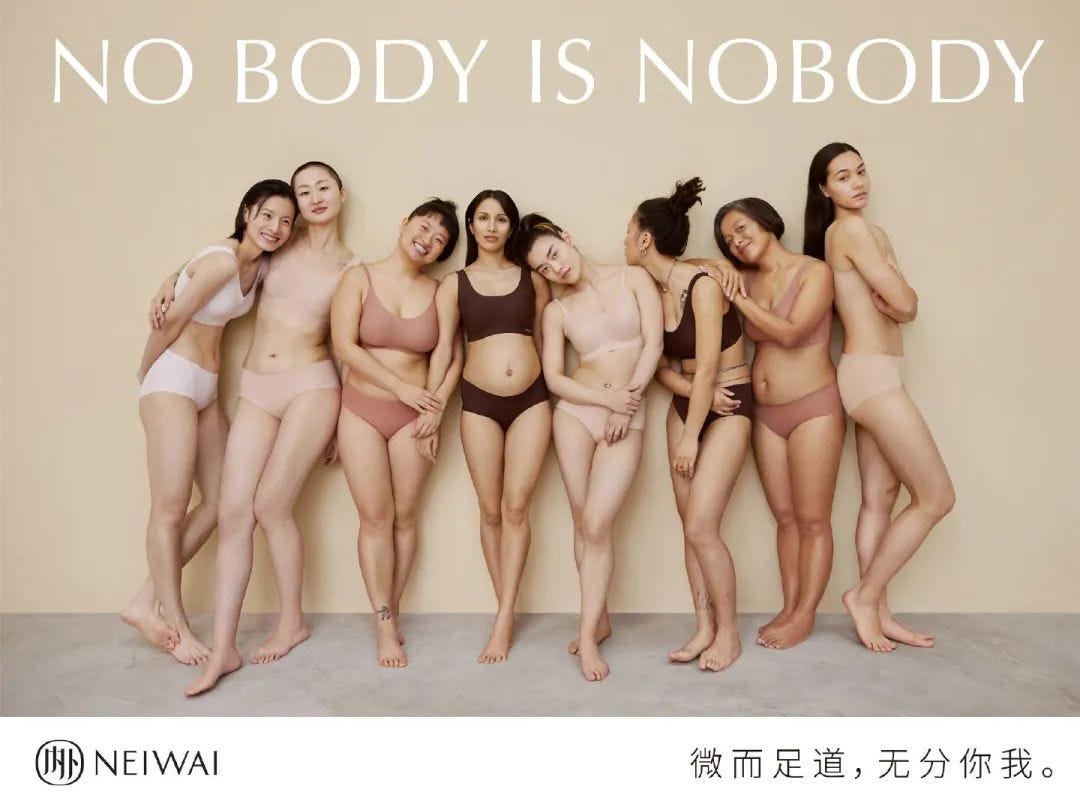

Dong's followers noticed his unusual behavior. Some protested against his unusual silence, accusing him of acting unprofessionally. This sparked the "underwear shame" discussion, where he was criticized for creating gender discrimination by acting "feeling ashamed" when selling women's underwear.

Dong responded to the public that he felt shy selling women's intimate wear. Despite this, it posed a significant challenge for the PR efforts. Later, Dong chose to remove all content from his Weibo account to close this PR crisis.

How to understand the event: From my personal perspective, I find it hard to believe that Dong intended any gender discrimination. Being shy and reserved has long been part of “China's personality”. Many netizens have striven to make progress and raise awareness about encouraging women to speak out. However, the current reality is that discussing intimate wear and other female-centric topics like menstruation remains sensitive for public discourse among many.

Dong's PR crisis nevertheless provides valuable insights into China's consumer market climate. Female consumers in China are increasingly embracing the idea that everyone has the right to love their bodies and are exploring topics such as women's lives, values, and empowerment more frequently.