China's first auction of public data; First AIGC copyright case- China Tech Governance Review Vol.2

China explores monetizing public data; broader implications for AI-generated content copyright in China.

Welcome to the Vol.2 of the China Tech Governance Review. In this article, I have selected two recent events of "first" feature that have attracted widespread attention in China to provide an introduction and observation.

One event is about a city in Hunan Province publicly auctioning the franchising rights of its main public data but soon announcing a suspension. From this, we may glean some insights into the situations of openness and market-oriented operation of public data in China, as well as the actual progress of the so-called "data revenue" that the market is concerned about.

The other event is about a Chinese court's first recognition of the copyright of works generated by generative artificial intelligence and its belief that these rights belong to the users of generative AI. Although the court tried to indicate its desire to encourage AIGC (AI Generated Content) creation and AI technology development, the industry has mixed reviews on the impact and effectiveness of this judgment. This may provide a glimpse into the increasing adaptability challenges of the current legal framework to generative AI.

Table of Contents

First auction of public data with a starting price of RMB 1.8 billion called off

China's first AIGC copyright case: the court upheld GenAI users' copyright claims

I. First auction of public data with a starting price of RMB 1.8 billion called off

On November 10, 2023, the Public Resources Trading Center in Hengyang City, Hunan Province, announced an auction project that quickly drew attention for its object and starting bid — the urban public data resources and smart city franchise rights of the city, with a starting price of 1.8 billion RMB. This marks the first time a local government in China has publicly sold the franchise rights to public data it manages. According to the announcement, the franchisee who wins the bid will be authorized to charge users within the franchise scope for the operation of the project during the franchise period as a return on investment. The industry generally interprets this as a public data operation mode similar to the PPP (Public-Private Partnership) model. Securities firms' research reports estimate that, assuming a 3-year operating right and an annual return rate of 10%, based on Hengyang City's GDP in 2022, and extrapolating to China's total of 293 prefecture-level cities, the national public data franchise operation market could be around one trillion RMB.

The domestic capital market was excited by this news for several days. However, dramatically, just five days later, the trading center issued a notice stating that the local administrative approval department had requested the suspension of this transaction. Media outlets attempted to understand the reasons for the suspension, but did not receive an official clear response. As of now, there is no news indicating whether and when this transaction might resume.

Notable info:

The announcement of this transaction actually came without many signs. Although earlier this year, Changsha, the provincial capital of the province, had issued regulations concerning the operation of the city's public data, proposing "to advance the marketization reform of data elements and increase government fiscal revenue," Hengyang had not released any similar supporting policies or proposals. From the information disclosed in the announcement, the project had received approval from the city's finance bureau and the municipal government before its publication, making it an official act of the local government. The sudden suspension possibly suggests intervention from a higher administrative level, and it's difficult to say whether the higher authorities had fully anticipated and approved the transaction.

Besides the somewhat embarrassing and unexpected nature of event development, the industry has also expressed concerns and controversies regarding two aspects of the transaction:

How the starting bid of 1.8 billion was calculated. The announcement marked the starting bid of 1,802,441,200 RMB as the result of asset valuation, but details about the valuation agency, the valuation report number, and the approving valuation institution were not provided. The lack of clarity on the standards used for pricing makes it difficult to effectively support its reasonableness.

The qualifications required of the franchisee. According to the announcement, the conditions for participating in the bidding and becoming the transferee are quite lenient: any enterprise registered in China with good financial and credit standing is eligible, without any special requirements. This seems to make it relatively easy for various market entities to participate in the public data market, despite several brokerage analysts telling the media that they expect the winning bidder to be a state-owned enterprise even if the auction goes ahead. Anyhow, compared to the starting bid, the lack and ambiguousness of requirements for the franchisee's technical and operational capabilities and experience makes the transaction appear more hasty, raising numerous questions in the industry about its commercial viability, compliance risks, and potential dangers to public interest and safety.

Viewpoints

Although the National Data Administration (NDA) has been established and there is a consensus on promoting the open circulation and utilization of public data, there is still much controversy over whether to directly open and share it with the public for free use or to develop it into data products or services for paid use. Although the "Twenty Measures for Data" propose from the perspective of distinguishing the purposes of data that "public data used for public governance or public welfare should be promoted for conditional free use, and public data used for industrial or sectoral development should explore conditional paid use", these guidelines just provide a space of imagination for monetizing and assetizing public data, lacking practical operability yet. Jiang Xiaojuan, former Deputy Secretary of the State Council and one of the core drafters of the "Twenty Measures for Data," recently stated that there are currently seven or eight models being explored for the development and utilization of public data. However, as most of these are related to government departments, and there are security concerns about opening the data directly to the public, "Some are in data exchanges, some in certain data-related ministries, and some are newly established state-owned enterprises handling public data issues within their domain." The transaction in Hengyang may be seen as an exploratory attempt and a test of market reaction. However, from its approach of bundling all main public data for a one-time auction sale of exclusive operating franchise rights, it's hard to see the local government's actual understanding of the value and commercialization of public data, appearing more as an urgent move to replace land revenue with data for local fiscal solutions.

"Data revenue" is becoming a focal point and hot topic for Chinese government departments at all levels, but this does not mean it is close to becoming a reality. In fact, no central policy document has yet formally established this guideline. Even in local policy documents, the related expression is mostly like "exploring the inclusion of authorized operation of public data in the scope of paid use of state-owned resources/assets, so as to 'feed back' local finances"[探索将公共数据授权运营纳入政府国有资源(资产)有偿使用范围,反哺财政预算收入]. In other words, it is not yet appropriate or mature to consider assetized public data as a major source of fiscal revenue. If the core of data revenue is to make public data a tradable and priced asset like land, the first issue to be addressed is how to standardize and measure the pricing of public data. Recently, the Price Department of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the NDA held a symposium with the Credit Reference Center of the People's Bank of China(PBCCRC), related banks, think tanks and enterprises to discuss the government-guided pricing issues for paid use of public data and proposed accelerating the establishment of a public data pricing mechanism and relevant institutional regulations. It seems that work in this area is mainly in its initial stages, but it has been put on the priority agenda of NDRC and NDA and is being accelerated.

In terms of exploring public data franchise operations, Hangzhou's efforts may be more noteworthy than Hengyang's. Hangzhou, where the headquarters of Alibaba is located, known for its vibrant internet and private economy, has just successfully hosted the 19th Asian Games. It was also the first city visited by the head of the NDA after taking office. The province where Hangzhou is located released administrative legal documents last year and this year regarding the management, use, and franchise operation of public data. In September, Hangzhou also released an implementation plan for the franchise operation of public data and openly solicited entities for public data franchise operation. From the implementation plan and solicitation requirements:

The policy goal, by the end of 2025, is to form a batch of valuable and promotable public data products and services, cultivate a number of ecosystem enterprises, and establish a basic public data infrastructure system related to property rights, circulation and trading, benefit distribution, and security governance.

The first batch of public data to be opened includes non-prohibited data in the financial, medical health, and transportation sectors — areas with strong market demand but also sensitive and complex, indicating a willing of substantive push forward. Other areas like commercial trade, market supervision, and culture and tourism are also on the list to be opened.

The specific implementation method is:

Hangzhou International Digital Trade Center, a state-owned holding company established by Hangzhou municipal government, constructs and operates the Hangzhou Public Data Franchise Operation Platform, serving as the unified online channel for franchise operation applications and information disclosure.

Eligible entities of interest submit franchise operation applications through this platform. The data administration department, in conjunction with relevant field supervisory departments (like the local financial regulatory bureau, health commission, and transportation bureau for financial, medical health, and transportation sectors, respectively), reviews and determines the franchise operation entities.

The data administration department signs franchise operation agreements with these entities, with a contract period of 2 years. The data administration department coordinates technical docking and data provision work with relevant field supervisory departments. Departments of development and reform, industry and information technology, finance, and market supervision are responsible for external supervision of daily operations, while cyberspace administration, public security, encryption management, and national security departments handle external security supervision.

The qualification requirements for applicant entities mainly reflect professionalism in data management and security, such as having relevant internal departments and responsible personnel and mature capabilities evaluated in network security and commercial encryption security.

Regarding operation costs, responsibilities, and revenue distribution, what is currently clear is that the construction and maintenance costs will mainly be borne by the franchise operating entity, and the franchise operating entity and data users will primarily assume possible security risks and responsibilities. Revenue distribution follows the principle of "benefiting according to input and contribution." Public data pricing and paid-use methods will be jointly studied by the data administration department and the pricing supervisory department, with an open and exploratory attitude towards cost sharing, profit sharing, equity participation, and intellectual property sharing.

Public data products for paid use, formed through franchise operation, are in principle listed and traded through Hangzhou Data Exchange.

Hangzhou's data administration department recently announced Ali Health, an associated entity of Alibaba, as the first public data franchise operation entity in the medical health field. There is no update for the financial and transportation sectors.

Last month, Hangzhou's data administration department held a closed-door meeting for data bureau directors from various regions, with over 30 data administration department heads and data group leaders from different provincial capitals attending. They discussed strategic cooperation for building a unified big market for data elements and cross-regional cooperation on public data franchise operations. Hangzhou seems to be making efforts and aiming to become a forerunner and leader in public data operations.

II. China's first AIGC copyright case: the court upheld GenAI users' copyright claims

Brief description:

On November 27th, China's first AIGC(AI Generated Content) copyright infringement case was adjudicated at the first instance. The court affirmed that the images generated by the painting large model belonged to the works protected under copyright law, and the user who operated and completed the image generation with the large model owns the copyright.

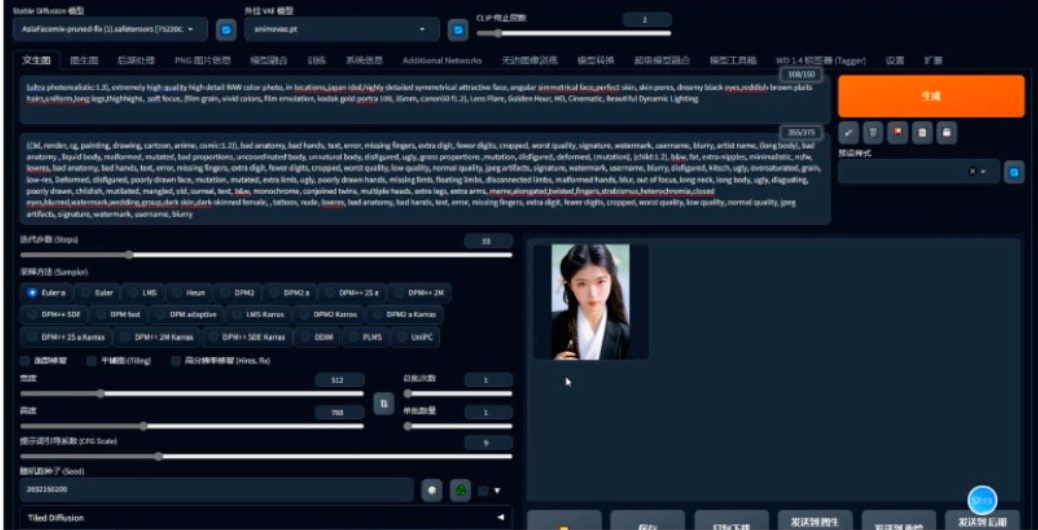

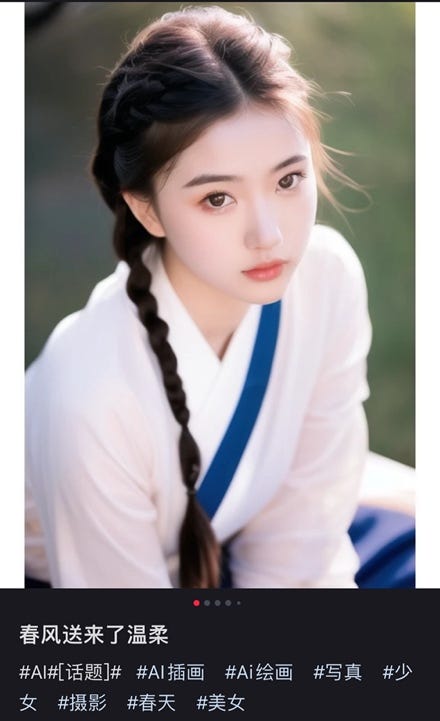

According to media reports, the plaintiff in this case was actually a lawyer. He previously wanted to represent an AIGC case but couldn't find an AI user willing to assert their rights. Consequently, he decided to create his own conditions. Using the well-known open-source text-to-image generation large model Stable Diffusion, he produced images and published them on social media. Subsequently, he used search engines to find potential infringement and identified the defendant. The defendant, a self-media blogger, used the image as an illustration in an article and removed the watermark. The plaintiff filed a lawsuit in the Beijing Internet Court, alleging that the defendant infringed upon his copyright of the AI-generated image and requested an apology and compensation of RMB 5000 for economic losses. After the trial, the court supported the plaintiff's claims but reduced the compensation to RMB 500. As none of the parties to the case appealed, the judgment is now in effect.

Notable info:

The case garnered external attention primarily on two aspects:

Whether the image concerned constitutes "works" protected under copyright law:

According to Chinese copyright law, for something to be considered a work, it must satisfy four criteria: (1) it belongs to the fields of literature, art, and science; (2) it has a certain form of expression; (3) it is an intellectual creation; (4) it possesses originality. The first two criteria are relatively easy to ascertain from the appearance of the image, thus the focus lies on the latter two.

The judgment indicated that to meet the criterion of the "intellectual creation," the images concerned need to reflect the intellectual input of a natural person. Examining the process through which the plaintiff generated the images, the court found that he had made certain intellectual input, such as designing the appearance of the figure, selecting and arranging prompt words, setting relevant parameters, and ultimately choosing the final image.

In terms of "originality", the court emphasized that the key is to review whether the generated image reflects the author's personalized expression, which requires case-by-case consideration. Generally, the more the requirements set by people using AI tools differ from others, and the more specific and clear their descriptions of pictorial elements and layout composition are, the more they reflect a person's personalized expression. The judgment focused on excluding the possibility that AI-generated images are "mechanical intellectual creation," which refers to intellectual work that is done in a pre-fixed order, consensus, and structure, and whose expression has the characteristic of "the same result regardless of who operates it", which does not have the personalized expression of a natural person. During the court examination, it was confirmed that the plaintiff, after altering certain prompt words or parameters, produced different image results. Ultimately, the court found that the plaintiff, by entering prompt words and setting relevant parameters, obtained an initial image and then continued to add prompt words and modify parameters, constantly adjusting and correcting, eventually resulting in the images concerned. This process of adjustment and correction reflected the plaintiff's aesthetic choices and personal judgment, did not constitute "mechanical intellectual creation," and demonstrated personalized expression, thus possessing originality.

The court stated that only by appropriately applying the copyright system, and encouraging more people to create with the latest tools, can there be more benefits to the creation of works and the development of AI technology. In this context and technological reality, AI-generated images, as long as they reflect a person's original intellectual input, should be recognized as works protected under copyright law.

If such AI-generated image constitutes copyrightable "work", who is the "author" with the copyright:

The court first excluded the large model itself, reasoning that under Chinese copyright law, the term "author" is limited to natural persons, legal persons, or non-legal entities capable of exercising human will. Generative AI models ("GenAI") do not possess free will and are not legal entities.

Moreover, developers of the large model were also excluded as they did not participate in the generation process of the images concerned and had no intention to create the images.

Furthermore, the agreement between the developer and the user, i.e., the open-source agreement, essentially waives the developer's claim to rights over the output. Consequently, the user, in this case, the plaintiff, was ultimately recognized as the author of the images concerned.

China, as a civil law/statutory law jurisdiction, differs from common law jurisdictions like the UK and the US. In China, individual case judgments do not have the force of case law and are not directly binding on other cases; they are merely of certain referential significance. The consensus or unified standards of legal interpretations and applications formed in judicial practice are required to be fixed and published through the legal document called judicial interpretations issued by the Supreme Court of PRC. Compilations of guiding cases released from time to time by the Supreme Court also have a strong directional effect on judicial judgments, and whether this case judgment will be selected for inclusion remains unknown.

Viewpoints

In this case, the court's overall approach was instrumentalism, i.e. viewing GenAI essentially as a tool for human creation. The premise of its reasoning is that intellectual input and originality are uniquely human attributes, with a focus on the extent of human involvement and dominance in the creation process. This was somewhat expected for two reasons, 1) currently, except for South Africa, major jurisdictions globally and their intellectual property authorities and courts hold a consistent view that the subject of invention or creation must be a natural person. The author, based on their free will, directly determines the expressive elements of the content, and current GenAI is not considered to have such autonomy; and 2) whether to grant GenAI legal entity status is not a matter for the judiciary to resolve, it falls under the purview of constitutional, civil, and copyright law legislation.

The achievement of the court was to propose whether works generated by GenAI possess copyrightability mainly depends on whether they reflect the original intellectual input of a natural person. The court provided a somewhat lenient interpretation of this standard, determining that the plaintiff's series of input operations to GenAI plus the generated work was not a "mechanical intellectual achievement" met this standard. This approach is similar to the stance of the US Copyright Office, which, following the "Zarya of the Dawn" case, published the "Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence" in March this year. The gist of this guideline is that if human operators exercise creative control over the material generated by GenAI, rather than merely mechanically reproducing it, and if the AIGC includes sufficient contribution from a human author, then it can support a copyright claim.

This judgment did not receive unanimous praise but became controversial after its publication. The industry generally believes that the specifics of the case are relatively basic and that more challenging issues have not yet been addressed, such as:

The court did not differentiate between autonomous generation and assisted creation in the context of GenAI creations – a distinction emphasized for its importance by the World Intellectual Property Organization in its 2020 document on AI-related IP policy issues. The perspective and viewpoint seemed to focus solely on assisted creation, without directly addressing and clarifying the copyrightability of works generated by artificial intelligence without human intervention.

What if the user does not use an open-source model like Stable Diffusion, which has a more relaxed stance on the rights to generated content in its open-source agreement, but instead uses a closed-source model, and the large model service provider stipulates it exclusively owns all rights of the generated content in the user agreement?

Do these prompt instructions and parameter fine-tuning schemes themselves have copyrightability? If the defendant did not directly use the generated object but obtained and reused the instructions and schemes to generate a similar picture, could it constitute infringement?

From the perspective of AIGC industry development, is this judgment a positive promotor? - It's currently hard to judge.

Some positive viewers affirmed the court's attitude in granting copyright to AIGC works to encourage AIGC creation, believing that this judgment gives AIGC a certain degree of exclusivity and monopoly, which can motivate users, enhance their willingness to use generative AI, and thus promote the development of the AIGC industry.

However, some internet industry representatives argued that for non-open-source large models (which most top Chinese large model manufacturers currently are), manufacturers need to invest heavily in acquiring training data. If users unilaterally own the copyright of AIGC, it could greatly affect the manufacturers' interests and reduce their motivation to further invest in R&D and service provision. Yet, others do not agree with this view, arguing that developers or GenAI service providers can recoup investment and profit in other ways, such as applying for patents on the large model itself, charging users licensing fees and service usage fees, rather than forcing users in the user agreement to accept that all intellectual property belongs to the developer/service provider. This could lead to content monopolies and negate the value of any form of creative input by the user, ultimately contravening the original intention of AIGC to encourage people to create.

Regardless of whether the copyright belongs to the GenAI developer/service provider or the user, it might be easy to overlook that the other side of the coin of copyright granted is the issue of potential infringement risk or responsibility:

On the one hand, there is the risk of infringement by AIGC itself with respect to the human works used as training corpus. A research team has pointed out that the probability that the likelihood of content generated by the Stable Diffusion model resembling dataset works by more than 50% is 1.88%. If it is agreed that the GenAI developer/service provider has the rights related to the generated content, it means the developer or GenAI developer/service provider is responsible for direct copyright infringement; if the user has the rights related to the generated content, the user is responsible for direct copyright infringement. The reality is more likely to be that the agreement is claimed as ambiguous or disputed, with responsibility being shirked when it comes to bearing it——Users blame on GenAI developer/service provider, and GenAI developer/service provider blames on open source training corpus datasets. After all, currently, the only entity that dares to claim to take on the compensation for possible infringement by users is OpenAI.

On the other hand, there is the risk of infringement when using copyrighted AIGC. Legal practitioners worry that the standard for creative intellectual input might be too low, leading to a large number of AIGC works being granted copyright. If someone follows the plaintiff's approach and initiates mass infringement lawsuits, even though RMB 500 per picture for infringement compensation might not seem high, if supported by the courts in bulk, the amount could be substantial. It is difficult to say that it won't form a new rights protection industry, not only consuming judicial resources but also raising the overall legal and economic risk level of the content creation industry, sowing the seeds of social conflict or even boycotting against AIGC.

Therefore, some believe that the conditions for granting copyright to AIGC works are not yet mature, or may not be appropriate for protecting AIGC creations. Even if AIGC works are granted copyrightability, as they become easier to produce and of higher quality, it becomes difficult for an ordinary person to discern from appearance whether an AIGC work reflects sufficient original intellectual input by its operator behind, thus making it challenging to determine whether to be concerned about copyright issues when using such works. Some further propose that considering the application of related rights (also known as neighboring rights). Compared to copyright, these rights have a more limited scope or relatively weaker constraints, do not require creative contributions, and can still meet certain incentive objectives.

In summary, expecting this judgment to align the interests of all parties involved in AIGC, as well as the general public, is clearly an overly optimistic expectation.

Fundamentally speaking, the design and construction of the intellectual property system are intended to balance the interests of creators and the public. On one side of the scale is the maintenance of creators' passion for creation to stimulate innovation, and on the other is to ensure that thoughts can be disseminated throughout society without being monopolized. Intellectual property laws, by recognizing the exclusive rights of creators to the results of their intellectual efforts, aim to encourage individual creativity to further public interest. Based on this principle, a consensus has formed in recent times that "law protects expression, but not ideas." However, as GenAI significantly lowers the threshold for content creation, it is also diluting the scarcity and proprietary value of human creative expression, making the current intellectual property legal system increasingly strained in providing effective solutions for distributing and balancing interests among all parties. Perhaps the autonomy of AI and its own interest claims are not yet widely regarded as an urgent issue, but at least one fundamental challenge to the intellectual property system is gradually being revealed: the boundary between thought and expression is becoming blurred with technological advancements. For legislators, regulators, scholars, and practitioners of this era, a more significant task may be to re-examine and properly step outside the property rights framework of the industrial era, returning to the starting point of this system for rethinking and reconstruction.