Dancing in chains: HUAWEI's comeback to the stage backed up by the Chinese semiconductor industry (Part II)

Integration Challenges for Chinese Semiconductor Industry

*This post is our premium content. Thank you for being a valued paid subscriber.

In the previous part, we focused on Huawei, the central figure in the Mate60 and Kirin9000S event, and analyzed some of the key aspects of the event. However, this series of articles is not intended to depict a hero's story like "The Return of the King" from "The Lord of the Rings." On the one hand, I do not possess the extraordinary talent of Mr. Tolkien, and on the other hand, whether it's for Huawei or China's semiconductor industry, it's not a gala time; the story may have just entered a new chapter but is far from over.

However, during this brief halftime break, we can take a moment to review how the Chinese semiconductor industry has developed in recent years and how it happened. In part III of the series, we will further look at the role Huawei plays in such a development process.

If you are not well-versed in the semiconductor industry, perhaps this pamphlet "Global Semiconductor Industry at a Glance" might be a helpful tour guidebook for a brief overview.

Chinese semiconductor industry: the industrial long march of decades

While Huawei's breakthrough of US sanctions in a short period of time may seem like a sudden achievement, the story of China's development of its semiconductor industry actually began not with the Biden administration, the Trump administration, or the Obama administration, but decades ago.

0 and 1

Old days, but not good days

In the 1950s and 1960s, the global semiconductor industry was still in its early stages of development, primarily focused on military applications during the Cold War. China recognized the strategic importance of semiconductor technology and began research in this field. In 1956, Premier Zhou Enlai initiated a call for advancing in science, leading to the Chinese government's plan to urgently develop technologies like computing, semiconductors, automation, and radio.

In 1965, China achieved a significant milestone when experts at the Shanghai Metallurgical Institute, led by Wang Shoujue, successfully reverse-engineered China's first silicon-based digital integrated circuit, although the gap with international standards was still around seven years. Unfortunately, further research was interrupted during the Cultural Revolution.

In the 1970s, before the era of economic reform and opening up, China had established a few semiconductor factories in Beijing and Shanghai. However, the technology and capacity remained relatively low, and the majority of semiconductor products were used for industrial and defense purposes without forming a commercial market. It wasn't until 1982, during the wave of economic reforms and opening up, that Wuxi Factory 742 introduced a complete integrated circuit production line from Toshiba in Japan. This marked China's first import of a full IC production line from overseas, setting the stage for the introduction of semiconductor technology.

In 1987, Morris Chang, who had long desired to establish a company specializing in semiconductor production, founded TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) in Taiwan, pioneering the foundry model. The same year, at the age of 43, Ren Zhengfei founded Huawei. Initially, the company was involved in importing and selling switches for telephone line connections. During this time, the global semiconductor industry saw Japan's decline, South Korea's rise, and mainland China exploring joint ventures with foreign companies in Shanghai and Beijing to process and produce integrated circuits for multinational companies like Philips and Japan's NEC.

In 1995, former Chinese President Jiang Zemin visited Samsung's semiconductor production line in South Korea. Upon his return, he described the gap as "astonishing" and declared that no expense should be spared to develop the semiconductor industry.

In 2000, China introduced industrial policy documents to promote the development of the semiconductor industry and offered tax incentives for foreign investment. In the same year, Zhang Rujing, who had left the now-TSMC-acquired WaferTech, founded SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation) in Shanghai with the goal of becoming a world-class foundry. This model included overseas registration, overseas investment support, and recruitment of overseas teams with advanced management and technical expertise. Subsequently, Taiwan companies were also attracted by favorable policies to establish semiconductor fabrication plants on the mainland.

New era, new crossroads

In the early 21st century, China was just entering the World Trade Organization (WTO) and had begun its path to becoming the "world's factory," leveraging its comparative advantage in low-cost labor. However, being at the lower end of the industrial value chain presented two significant challenges:

Low income and profits: China was producing a wide range of products, but most of them were low-value-added resource-based products. The production of high-value-added products was primarily dominated by developed countries. The relatively low-profit margin in China's manufacturing industry, coupled with the payment of high patent fees to foreign companies, further compressed profits. For instance, at that time, patent fees for mobile phones constituted 20% of the selling price, and for computers, it was 30%. These were a reminder that China needed to move beyond basic processing.

High resource consumption: China's GDP accounted for 4% of the world's GDP in 2003, yet its energy and resource consumption per unit of output were 2.4 times higher than the global average. As an example, China had to export 800 million shirts to import one Airbus A380. This was unsustainable for a country with limited per capita resources. It was clear that optimizing the economic structure and improving resource efficiency required technological support.

In this context, developing high-end emerging technologies and high-value-added industries, including semiconductor technology, became a strategic imperative for China. However, there was a debate within China's technology and industry sectors on whether to pursue indigenous innovation or a strategy of technology import and market exchange.

Technology import and market exchange: Advocates of this strategy believed that importing technology was faster and more efficient than trying to develop it independently. They argued that the technology import strategy in the 1980s and 1990s had improved China's product structure and technological level in many areas and facilitated the transfer of international industrial capacity to China. At the time, China's fiscal revenue was limited, and importing technology and exchanging market access for technology allowed for the rapid introduction of technology to the domestic market, while self-reliance through research and development required long-term investments and could lead to detached from practical application if technology levels were insufficient.

Indigenous innovation: Proponents of indigenous innovation argued that importing technology did not necessarily bring innovative capabilities. Much of the imported technology was used in a utilitarian manner and did not lead to secondary innovation. Reliance on imported technology could leave China dependent on others for crucial technologies and equipment. Without core technologies, China could be vulnerable to external influences. Because technology holders may choose not to sell or grant their core technology.

Given this backdrop, the Chinese government adopted a pragmatic approach - "Let's take both." This strategy aimed to address immediate economic needs by importing advanced technology and facilitating its rapid application while simultaneously laying the foundation for strategic self-reliance.

On the path of indigenous innovation, China initiated the development of a medium- to long-term science and technology development plan. In 2006, China released the "National Medium- and Long-term Program for Science and Technology Development (2006-2020)" (《国家中长期科学和技术发展规划纲要(2006--2020年)》) which identified 16 major research projects. The first two of these projects were related to the semiconductor field: "Core Electronic Components, High-End General Chips, and Basic Software" ("Project 01") and "Ultra-Large Scale Integrated Circuit Manufacturing Equipment and Complete Process."("Poject 02") It marked the beginning of China's strategic push into the semiconductor industry and high-end technology development.

Got a plan, so how to execute it?

Chinese government noticed that the semiconductor industry is technology-intensive and capital-intensive, naturely, it decided to lead and promote the technological advancement and provide substantial financial support.

Technological research and development:

The Chinese government designated the weakest links in semiconductor technology as key research and development projects. These projects involved a combination of universities, research institutions, and businesses that were responsible for undertaking the research and development efforts. The government played a role in coordinating, providing financial support, and monitoring the progress of these projects.

Project 01: Led by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the Project 01 aimed to make technological breakthroughs in high-end general-purpose chips, basic software, and core electronic components. It comprised 220 individual projects and engaged over 300 companies, universities, and research institutions. Key areas of development included high-performance CPUs, digital signal processors (DSPs), System-on-Chips (SoCs), and the development of platforms, IP cores, and EDA tools. Additionally, it focused on basic software products such as operating systems, database management systems, middleware, and office software.

Project 02: Led by a joint leadership group comprising the Ministry of Science and Technology, the National Development and Reform Commission, and the Ministry of Finance, concentrated on the research and development of semiconductor key manufacturing equipment, materials, and processes. Projects in the Project 02 had a heavier emphasis on industrialization and involved a stronger industry-led initiative. After a nationwide selection process, over 50 projects were established, with businesses, leading research organizations, and universities forming research laboratories or alliance organizations to facilitate production, education, and research. The total investment in these projects exceeded CNY 18 billion.

Financial support:

The Chinese government understood the significance of semiconductor industry development more deeply during the promotion of the Projects, especially with the rapid proliferation and growth of smartphones and mobile internet. This realization was accompanied by the understanding that domestic semiconductor companies, which were relatively new and lacked significant accumulations, faced challenges in sustaining research and development due to limited initial profits. To address these issues and expedite industry growth, the government implemented various economic support policies and financing tools:

Economic and tax policies: China introduced a range of economic policies and tax incentives aimed at fostering the semiconductor industry's development in 2011-2012. These policies, primarily targeting specific IC manufacturing companies with certain technologies, continued and expanded the measures introduced in 2000.

National Integrated Circuit Industry Development Promotion Outline (2014)("IC Outline 2014"): The IC Outline 2014 outlined objectives to achieve more than CNY 350 billion in semiconductor industry revenue by 2015, with an average annual sales revenue growth rate of over 20% by 2020. In the same year, the Ministry of Finance established the "National Integrated Circuit Industry Development Investment Fund" (commonly referred to as the "Semiconductor Mega Fund" or "Mega Fund"), with the government as a major shareholder along with other state-owned capital providers, including China Development Bank Capital, China Mobile, and China Tobacco. The first phase of the Mega Fund ("Mega Fund I") raised CNY 138.7 billion, intended for equity investment in enterprises along the semiconductor industry chain. The Mega Fund I employed two primary equity investment methods: direct equity investment and cooperation with regional funds and social capital to establish subsidiary funds. Direct equity investment was the dominant approach, and more than 60% of the projects invested in by Mega Fund I were businesses supported and nurtured in the early stages by the Projects.

Credit support: Credit support was provided to integrated circuit enterprises through policy banks, such as the local branches of the China Export-Import Bank, and commercial banks. For instance, the Shanghai branch of the China Export-Import Bank offered long-term credit support to key IC enterprises in the industry chain, including SMIC, Cmsemicon (中微半导体), Glaxycore (格科微电子), Zingsemi (新昇半导体), and more.

Local investment funds: Local governments established investment funds dedicated to the semiconductor sector. As of 2018, a total of 17 provincial and municipal industry funds were established or announced. The collective target size of these 17 local industry funds reached CNY 500 billion.

The central aim of these policies and funds was to leverage national funds to attract significant private capital into the semiconductor industry.

What were the interim results?

Let's turn the clock back to 2017, before the occurrence of the US sanctions on ZTE, to examine the situation at that time:

Major Projects:

Project 01: By 2017, nearly 500 entities participated in the project, contributing over 50,000 R&D personnel and achieving an additional output value of over CNY 130 billion. Notable breakthroughs were made in core technologies, resulting in the narrowing of the gap with foreign counterparts from over 15 years to around 5 years. Self-reliance in core electronic components increased from less than 30% to over 85%. China's supercomputer CPU (double-precision floating-point peak performance) achieved a speed of 30 trillion operations per second, marking a 600-fold improvement in CPU performance compared to 2006, reaching international standards. Over 7,800 patents, more than 2,500 software copyrights, and integrated circuit layout designs were registered.

Project 02: By 2017, this Project has successfully developed high-end equipment and materials, including advanced etching machines and thin-film deposition equipment. Over 30 types of high-end equipment and materials were developed, with performance levels reaching international standards. Progress was made in the development of manufacturing processes, with improvements of up to five generations in areas such as 55/40/28nm. Additionally, progress was made in the 20-14nm process development, and self-owned intellectual property rights were achieved. Packaging companies transitioned from low-end to high-end, reaching international standards in three-dimensional high-density integration technology. The project achieved cumulative sales revenue of over CNY 180 billion, accounting for over half of the total sales revenue of participating companies. Project 02 also played a direct role in cultivating leading companies in the semiconductor industry, such as NAURA Technology (北方华创), Cmsemicon (中微半导体) and Piotech (沈阳拓荆).

The expert team from the acceptance committee conducted an on-site inspection of the prototype of the photolithography machine stage, developed at Tsinghua University's IC Equipment Research Laboratory's cleanroom. The technical achievements of the Projects essentially cover the entire IC industry chain, changing the situation where core equipment and process technology were entirely imported from abroad. This has laid the foundation for semiconductor equipment, materials, process support capabilities, and IC manufacturing industry chain. In some areas, it has reached internationally advanced levels.

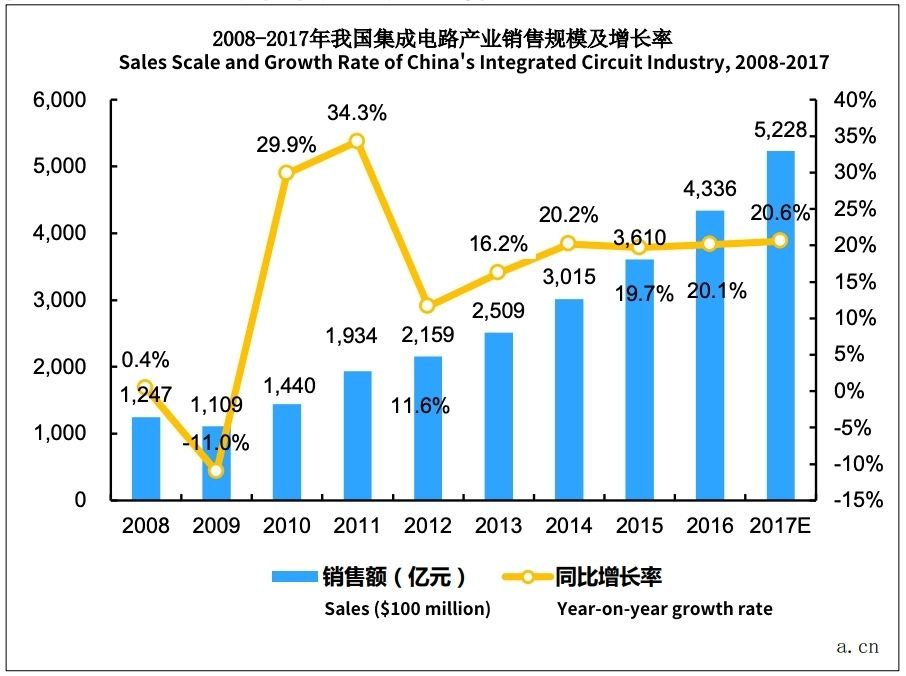

Realization of IC Outline 2014 goals: In 2015, China's IC sales reached CNY 3,610 billion, marking a year-on-year growth of 19.7%. China maintained IC sales growth rates exceeding 20% in both 2016 and 2017, indicating significant growth. The chart below shows the scale and growth rate of China's IC industry sales from 2008 to 2017. (Source: 清科研究中心)

Mega Fund I investments: Mega Fund I's initial phase invested approximately 63% of its shares in the wafer manufacturing field. Key investments, such as in SMIC, contributed to the significant reduction of technological gaps with international leading-edge manufacturing processes. Semiconductor packaging companies, supported by the fund, also achieved notable growth and entered advanced fields. Companies like JCET (长电科技), HT-Tech (华天科技) and TONGFU Microelectronics (通富微电子) ranked among the Top 10 global packaging companies in terms of revenue in 2017.

Industry investment and financing: In response to Mega Fund I's contributions, newly-secured social financing (including equity financing, corporate bonds, bank loans, trusts, and other financial institution loans) reached approximately CNY 514.5 billion, roughly 3.7 times the amount raised by the first phase of the fund. The global wave of semiconductor industry mergers and acquisitions during this period also contributed to a significant increase in the number and size of domestic semiconductor industry mergers and acquisitions. Between 2012 and 2017, China's semiconductor industry witnessed 516 merger and acquisition cases, amounting to CNY 193.7 billion. As shown in the following chart (Source: 清科研究中心), you may also observe the surge that began in 2014.

In simple terms, the overall result is: China has undergone a significant transformation in its core semiconductor sectors in approximately 10 years, starting from scratch and gradually establishing a complete industrial chain. This period witnessed swift advancements in wafer manufacturing and testing, and being led by state-owned capital, the flood of money into the domestic semiconductor industry has contributed significantly to the expansion and consolidation of the industry.

Keep proceeding: nonlinear difficulties

However, transitioning from 0 to 1 and progressing from 1 to 100 are distinct challenges. Achieving not only a complete semiconductor industry chain but also a prominent international position as a whole becomes increasingly difficult and nonlinear. Strategies effective downstream in the value chain may not necessarily apply as efficiently when moving closer to the core upstream areas.

The government-driven industry incubation model also faces several issues, as the visible hand cannot replace the dominant role of market economics and the natural laws of industrial development. Powerful adversaries in the global semiconductor market and the geopolitical arena are fully exploiting their advantageous positions. Both internally and externally, China’s semiconductor industry faces significant resistance and challenges.

Continue reading to further understand the specific aspects of these nonlinear challenges and the exploration by the government and semiconductor industry of China to overcome these difficulties. A case study on the "Hefei Model" will illustrate endeavors and results to foster industrial aggregation and build an ecosystem through government-led equity investment funds and an efficient market-oriented local government.