Has China's younger generation really chosen to 'lie flat'?

3 real stories of how Chinese youth are navigating a tough job market

China's youth unemployment has reached new heights, and the narratives surrounding "躺平" (lying flat) have been rampant. The media often associates much stigma with the youth, depicting them as "helplessly" reducing their expectations and leaving big cities because the economy has failed to reward their efforts.

In fact, hashtags like #躺平 (lying flat) and #裸辞 (naked resignation, or quitting a job without a backup plan) have become attention-grabbing buzzwords on social media, and vloggers/bloggers usually see their traffic boosted when they include these hashtags, as they do resonate with many anxious young Chinese.

While this narrative has gained traction, I don’t want to reduce everything to a simple story because, truthfully, not everyone is "lying flat." For some, "lying flat" is a rational choice for a simpler and more stable lifestyle, while many others are actively seeking different paths. Today, I want to share three on-the-ground observations that help unpack the youth unemployment numbers and provide insight into what Chinese youth are actually doing in this competitive job market.

This week is China’s National Day Golden Week holiday, and I hope these stories make an interesting addition to your reading list! Happy holiday, everyone!

Story 1: Why some young Chinese "laid flat" – the disillusion of rapid “social class leap”

In the past two decades, rapid growth in sectors like finance and IT has generated numerous "get rich overnight" anecdotes in China. These stories are highly sought after, and much of the country embraces the idea of meritocracy, believing that putting in maximum effort will lead to abundant rewards - this belief has largely held true over the decades. First-tier cities have become the best places for making money and achieving the leap of social class.

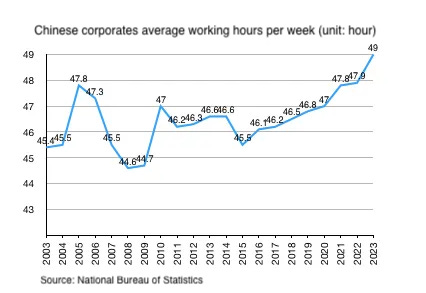

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, working hours for Chinese laborers have steadily increased, with the average weekly hours in 2023 reaching 49 hours — the highest in nearly twenty years. Despite Chinese labor laws limiting daily hours to 8 and weekly hours to 44, overtime work has long been prevalent and is increasingly common.

The widely criticized 996 culture (working 9 AM to 9 PM, six days a week) is actually a complex issue. Many people aren’t directly “forced” by their companies; instead, they “voluntarily” embrace the 996 lifestyle at major firms because overtime often leads to promotions, overtime compensation, and hefty bonuses. (As a matter of fact, it's fairly common to see that a big portion of the income relies on the "overtime" pay). This enables them to afford expensive mortgages in first-tier cities and pursue dreams of becoming middle managers earning over a million yuan a year, affording luxurious lifestyle, allowing their children to attend international schools and such.

However, as the new economy slows down, many are starting to disillusion with the idea of a drastic "class leap". When the high costs of living and work pressure no longer yield excessive rewards, more people are choosing to return to their hometowns.

Below is a story reported by Caixin in Young people who returned to their county towns for work; Some paragraphs redacted for simplicity:

Many didn’t initially plan to go back.

Take L, who once dreamed of escaping her county town. While in high school, she vowed, "No matter what, I will get out and never come back." She felt confident about her future—during her master’s program at a prestigious university in Beijing, she believed she was on a clear path to upward mobility. She thought big cities were filled with "impressive people" where she could "make a lot of money and realize my worth."

But her dreams faded after entering the workforce. Her life revolved solely around work. After long days, she would go home to lie down, rarely socializing on weekends and making few friends. While she earned more than in her small town, it felt like money was just spent locally, with little to take back home.

Work also lacked fulfillment. Over time, she realized she was just a cog in the machine, struggling to make her voice heard. Housing was another major issue. She quickly recognized she might never be able to buy property in a big city; she couldn't afford it, and her family couldn't help. Yet she longed for her own home, which symbolized belonging.

She also noted that the job market had become "less favorable." A married colleague with a child and a mortgage told her that the company wasn’t doing well, and at their age, finding stable civil service jobs was now the goal.

“Staying in a so-called big city means facing high housing costs, relentless overtime, and the loneliness of having no friends, all in hopes of a 'chance to turn things around.' But the resources in big cities are only accessible if you’re in the right circles, and I feel like just another worker,” L shared.

L’s family is from a county town in Jiangxi, which has a high-speed train station, making travel convenient. With delivery services and community buying options available, she has almost replicated her city life. These are sources of her happiness.

However, not all county towns develop equally. Tian, from Xingtai, Hebei, feels the stark differences between her county and big cities. Her county lacks convenient transportation, with no trains or high-speed rail, and rides can be hard to come by. There are no large shopping malls, only small supermarkets. Outside of work, entertainment options are limited to reading or visiting other counties.

The scarcity in small towns isn’t just about resources. Wang, from a county in Shijiazhuang, describes life there as "monotonous." Before returning to her county, she envisioned a life of tranquility: “Not busy with work, no overtime, leisurely rides home at sunset, enjoying home-cooked meals, and traveling with friends—simple and stress-free.”

This is indeed the case. County jobs have less rigid time constraints and offer more freedom. Yet, this freedom comes at a cost; she increasingly feels a lack of spiritual fulfillment. “My friends work in big cities, and scheduling meetups is tough. There aren’t many entertainment facilities in my county, and it can feel quite boring compared to the various activities and exhibitions in cities,” Wang noted.

The story is a snapshot of many young Chinese who have chosen to quit their demanding jobs. There have even been some "unintuitive" observations that some companies and factories are having trouble hiring workers, even amid a rising youth unemployment rate.

Stability versus ambition presents a trade-off: small-town life offers freedom but with limits, while big companies provide opportunities but come with restrictions. Those young people who are “lying flat” aren’t failures in big cities; many have experienced life there, realized their true desires, and chosen stability—not as a surrender, but as a conscious decision.

Story 2: Refusing to be a "good student," some young Chinese seek personal fulfillment

In China, many parents believe that working hard and following their bosses’ instructions are the paths to a promising career. However, those who frequently switch jobs and abandon stable lives at big companies are often seen as "unruly." Yet, many young people from the '90s and '00s generations are choosing to break away from this “textbook” route and seek careers that align with their strengths.

This narrative of being a "good student" versus being the "unruly" permeates almost every stage of life for a typical Chinese.

Let me share a real story about a friend of mine. Like me, she was born in the '90s and worked at big tech companies in Beijing, changing jobs multiple times in just two years and shifting roles internally five or six times in just a year. Yet she remained dissatisfied with the workplace environment. She faced long hours, bullying from middle management, and even instances of workplace harassment.

She tried roles in HR, operations, and purchasing before becoming an assistant to the president in the C-suite office—a position many new graduates envy for its promising career path and proximity to upper management. Just when it seemed she was getting her career on track, she chose to leave and become a full-time psychological therapist.

She explained that her motivation for staying at the internet company for so long was to experience and understand the real dilemmas and pressures faced by young white-collar workers, which would ultimately help her become a better therapist. While working full-time, she completed part-time training for her counseling certification and didn’t put much effort into her “real” job. Instead, she “secretly” read psychology books during office hours—what many young people might call "摸鱼" (slacking off).

She said, "I believe that a good therapist needs both talent and genuine personal character. This is a career I excel in and love. Now, I'm very happy—I can sleep until the afternoon, work just twenty hours a week, and earn even more than before. In a city like Beijing, I can make 30,000 yuan a month, which is almost comparable to the salary of a mid-level manager at an internet company. My talent in psychology allowed me to achieve in a few months what many of my predecessors accomplished over years. I’m grateful I chose to pursue what I’m good at."

In the eyes of older generations, she is considered "unruly." She switched majors multiple times in college, pursued two master’s degrees without working after graduating from college, and job-hopped frequently, moving homes five or six times in two years in face of rising rent. Even her parents sometimes struggled to understand her choices, believing she was simply "not listening to her boss." Yet, it is this "unruliness" that has helped her discover her true talents and provide meaning and motivation in the face of intense pressure in big cities.

Recently, discussions around freelancing and "digital nomad" have exploded on the Chinese internet. Young people are beginning to explore their identities, moving away from the pursuit of promotions, executive positions, and the "glamour" of sectors like internet and finance, instead seeking to understand their own strengths and interests.

A significant number of these "unruly" young people have launched new consumer and service businesses in China, including restaurants, bars, fashion brands, and counseling services. The value added by China’s service sector accounts for only 56.7% of GDP, while in Japan for instance, it exceeds 70%. I believe that in the future, these "unruly" young individuals will have ample opportunities to leverage their unique experiences to innovate in the consumption and service industries.