"Overcapacity" or "involution"? How China's manufacturing suffers from over-competition

Tracing the roots and perils of China’s manufacturing involution: where lie the future opportunities?

"内卷involution" a term borrowed from sociology in the Chinese context, describes a societal phenomenon where intense competition and skewed resource distribution drive individuals to increase their efforts in a self-defeating cycle, leading to no real progress despite escalating inputs --- or alternatively described as "overcapacity" by US Secretary Yellen.

The issue of overcapacity in China has recently been thrust into the spotlight following comments by Yellen, who claimed that China is flooding global markets with cheap goods. Last week,

wrote in his personal newsletter that this over-capacity, if true, was beneficial for global consumers at the expense of China manufacturers. It’s not an ideal situation that Chinese manufacturers love to see.Since the pandemic outbreak and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the United States has accelerated its plan to replace China in the global industrial chain, with manufacturing industries in India, Vietnam, and Mexico rapidly emerging. Some domestic optimists believe that China's intensely competitive market has nurtured a host of internationally competitive enterprises. As these enterprises go global, Chinese manufacturers accustomed to the 996 work culture(*) are expected to "out-compete" Western companies familiar only with holidays and strikes, potentially leading to a new era of glory on the international stage. This view is quite common.

Baiguan: 996 working hour system refers to a work schedule in China's companies that require workers to work from 9:00 am to 9:00 pm, 6 days per week

However, today's post offers a more critical perspective, arguing that "involution" represents a low level of excessive competition. Prolonged involution stifles the vitality of enterprises, necessitating a reflection on and eradication of the involution culture. This insightfully points out that the involution in China's manufacturing sector shares the same traditional mindset as the educational system's involution — the "support the strong" mentality. Policies favor industry leaders in hopes that they will achieve global prominence, just as top-performing students in basic education receive more attention and resources to help them enter better schools, thus enhancing the school's reputation. This approach exacerbates market distortions and imbalances, whereas the strength of manufacturing lies in its industrial ecosystem, the health of which depends on the diversity of SMEs.

Below is Baiguan's translation of the original article written by Haoyang Wu, the Business Director for Greater China at MAKA Manufacturing Systems GmbH. (Some paragraphs are abbreviated or redacted):

Not a badge of honor, nor a practice to promote

Involution represents low-level competition

Outstanding companies and business leaders are known for their relentless drive, as exemplified by figures such as Thomas Edison, Kazuo Inamori, Jack Welch, Steve Jobs, and Elon Musk, who even demonstrated tendencies of "self-exploitation." However, their intense effort was directed toward experimenting with new technologies, testing new methods, and developing new products. Their goal was a disruptive innovation, not merely working overtime for hard-earned money.

Many companies that excel in "involution" are indeed adept at controlling costs, with highly refined internal control systems. However, management systems perfected through involution often come with severe internal friction and impede innovation. Over a decade ago, I worked with a mobile phone company where discrepancies in the warehouse's inventory records for screen protectors were discovered. It turned out that operators would often "steal" a few protectors to sell to vendors for a small profit. Thus, several additional steps involving counting and signing off were introduced during the material handover process: from the warehouse to the workshop, items had to be counted and signed off face-to-face, and the same was required when workshop team leaders distributed them to each operator. Each count involved thousands of items, and a mistake required a recount, taking about 10 minutes. Although this ensured precise cost control down to the cent, it came at the expense of 10 minutes per person per shift.

Many large corporations assess KPIs with extreme precision, treating each employee as a cost center to be independently accounted for. Since KPIs are directly linked to income, teams are both constrained and cooperative, leading to mutual suspicion among departments and individuals. This type of management system is a typical result of "involution." While it minimizes individual costs, it leads to significant internal waste and is extremely detrimental to innovation. Companies employing this management strategy are found worldwide, differing only in degree. They are predominantly in traditional industries and large companies, mostly in China and East Asia.

Innovation can’t be designed, nor can it be forced through over-competition

In "Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned: The Myth of the Objective," written by OpenAI's Kenneth Stanley and Joel Lehman, an intriguing idea is presented: the last human scientific endeavor to follow a detailed plan successfully was the Apollo moon landing. Most other significant technological advances have occurred serendipitously, building upon existing achievements, such as the success of ChatGPT. In cutting-edge fields, overly detailed goals and specific plans can actually hinder breakthroughs and innovation. Setting clear objectives can limit explorers' search areas, providing misguided ideas and directions. The phenomenon of "involution" involves accelerating research and development based on set detailed goals and specific plans. This approach can be detrimental when it includes penalties for not meeting deadlines, bonus deductions, and eliminating team members who lag behind. Such "involution" mechanisms are only suited for tasks with clear objectives and are unlikely to yield great products. This methodology essentially stifles the creative unpredictability that often sparks monumental innovations, reinforcing the argument that true advancements require a degree of freedom and flexibility beyond rigid targets and schedules.

Competition in involution: battling domestic counterparts

Chinese companies typically struggle to succeed in overseas markets through price wars alone. When companies from China enter a market with similar cultural and resource characteristics, fierce homogenized involution usually begins. If Western manufacturers find themselves unable to compete on price, they often choose to enhance their product value and move into the high-end market to maintain differentiation from their Chinese counterparts, or they may abandon the market altogether to focus elsewhere. However, when a Chinese competitor enters the same market, they tend to promote similar products at even lower prices. Once differentiation in product and market positioning vanishes, "involution" begins.

In 2018, I assisted a Chinese publicly listed company in acquiring a German firm. The company sent a vice president who was quite fluent in English and spent an afternoon explaining market positioning to the Germans. His strategy was as follows: first, identify the company's most competitive products and promising markets, then pinpoint which competitor's product was performing best in these potential markets. Next came the standard operation of "involution": he directed the acquired German company to develop equipment similar to this competitor's star product, but with either lower costs or enhanced features.

The Germans exchanged uneasy glances and nodded politely, seemingly agreeing that the vice president had some valid points but feeling that something was off without pinpointing what exactly it was; it simply wasn’t the approach they were accustomed to. This underscores the difference between "homogeneous competition" and "differentiated competition." Chinese companies are overly familiar with the former, often described as "involution," and thus sought to replicate their domestic success in Germany. However, European companies pursue differentiated competition. While the two leading companies might seem comparable, their underlying business strategies differ vastly. Typically, European equipment manufacturers focus more on their technical systems, securing orders in specific markets with their preferred technological solutions. Instead of copying or imitating, it's better to develop new technologies based on existing technical expertise. Considering the myriad of technological options worthy of investment and development, why settle for what's left over by others?

Homogenized involution stifles innovation, especially among SMEs

Homogeneous competition stifles innovation, as the first to innovate is often the first to be copied. Pioneering products entering the market are easily imitated. Coupled with a severe lack of intellectual property protection in domestic markets, only well-capitalized large companies dare attempt minimal innovation.

I know a business owner in the mahogany furniture industry who developed a highly innovative furniture design technique. However, he is hesitant to launch his product on the market. He understands that once the product is released, it won’t be long before experts in the field decipher the technology and produce similar designs. Therefore, his strategy has been to scale up his production capacity first. By mass-producing the new product as soon as it hits the market, he aims to saturate the market quickly, leaving no room for competitors to imitate and catch up. While this strategy is seamless in theory, the unfortunate reality is that the product has yet to be launched.

The illusion of superiority in "out-competed" enterprises

Enterprises shaped by "involution" and those cultivated through normal market competition differ significantly in competitiveness and survival capabilities. In homogenized "involutionary" markets, the strategic demands on companies are minimal. Businesses must emulate industry leaders without taking risks or exercising independent judgment. In contrast, strategic decision-making is crucial in a normal competitive market environment. Companies have the freedom to decide where to achieve strategic breakthroughs, whether in design, processes, materials, equipment, or supply chains, rather than merely competing on costs and delivery times.

Breakthroughs in R&D render mere competition futile

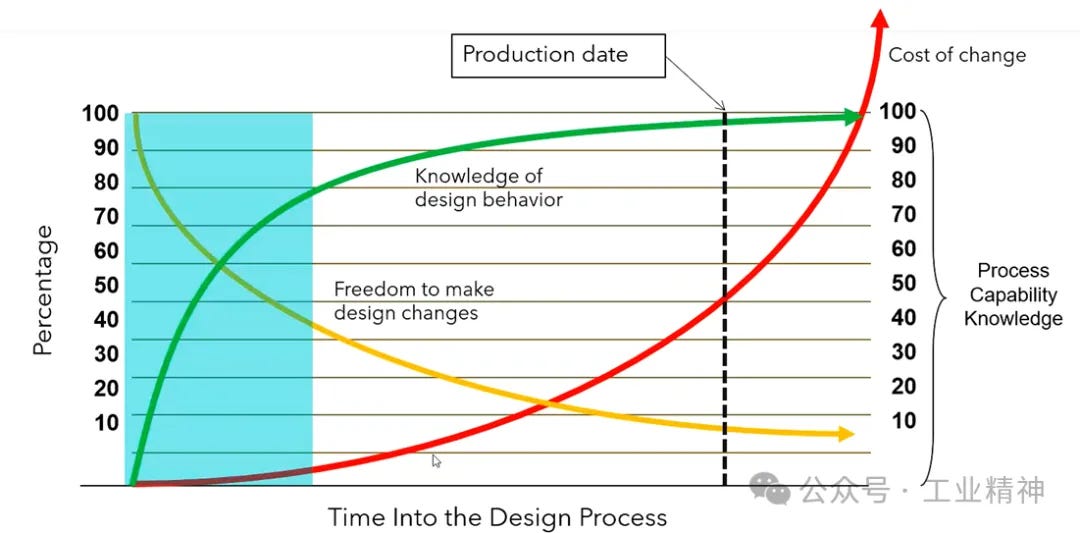

The concept of "involution" in manufacturing essentially revolves around production management. However, according to the principles of Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DFMA), making adjustments and changes after a product has entered mass production incurs significant costs. It is far more economical to address potential manufacturing and assembly issues during the design phase itself. Thus, a well-thought-out design and robust process can substantially reduce both equipment investment and production costs.

The graph presented here is an original creation, where the x-axis represents research and development (R&D) duration, and the y-axis illustrates both costs and returns. Investing in the physical theory stage of R&D can yield a return on investment (ROI) several times over, but the development cycle exceeds ten years. Product design and process stage investments require 3-10 years, with ROIs exceeding 50%. Once product blueprints and processes are finalized, efforts can only be directed toward improving production equipment. A more efficient machinery can deliver substantial ROI, though the associated costs are usually higher than those in the product and process design phases. When equipment selections are also finalized, the focus shifts to enhancing the rationality of factory logistics layouts, automation, digitization, and various aspects of factory management. There is always room for improvement in factory management, but the cost-effectiveness is relatively low. A factory operating under a strict 996 schedule and well-established systems may outperform a standard factory by 20% in efficiency. Even with the realization of Industry 4.0 and full automation, efficiency gains do not surpass 30%. However, a successful R&D project could potentially double the returns.

In the 1970s, thanks to its low labor costs, Japan's electrical and electronics industries developed rapidly, producing affordable and high-quality electronics that significantly challenged American companies, including IBM. Recognizing that competing on price with its Japanese counterparts was futile, IBM sought solutions at the source—by improving design and simplifying the assembly process to reduce manufacturing costs and, consequently, prices. One classic example involved an assembly process that used no screws and required no tools; one person could comfortably complete the installation in just 3 minutes and 25 seconds. This innovation established IBM as a pioneer of Design for Assembly (DFA).

In manufacturing, assembly is often the most labor-intensive cost component. However, when products are optimized for easy assembly, the need to complete this step in a factory is eliminated, allowing customers to assemble the products themselves. The fundamental technical logic behind IKEA's success lies in its standardized mass production, which shifts the assembly responsibility to customers, thereby reducing manufacturing costs and the final purchase price for consumers. IKEA, a company from Sweden, is situated in a region where companies are globally renowned for their exceptional employee benefits, and the concept of "involution" is virtually absent from their vocabulary. Thus, truly successful businesses thrive on intellectual prowess.

To maintain its competitive edge, IKEA has not ceased its research and development efforts. According to the latest insider information, IKEA is collaborating with an Italian company to develop a highly efficient, fully automated, flexible cabinet assembly system. This system can assemble a cabinet in just seconds, and the cabinets can vary in size and specifications from one to the next.

The first production line is currently being tested. Once it reaches full production capacity, the labor cost advantage of China and Southeast Asian countries in the panel furniture industry will likely be neutralized entirely, marking another instance of "smart work" overcoming "hard work."

Therefore, the closer the investment in the early stages of R&D, the higher the technical risk and the greater the potential for significant achievements. Conversely, focusing on meticulous management in the latter stages of production carries no technical risk but requires a considerable amount of effort. When the pursuit of such lean management becomes obsessive, "involution" begins.

Lean production is merely a foundation, not a guarantee of success

Many of China's top manufacturing enterprises are intensely focused on "involution" through lean production, striving for operational excellence. Although this is not inherently wrong, the benefits of lean production have their limits. Once a certain level of efficiency is achieved, the focus should shift toward research and development, and innovation. Pursuing lean practices without balancing them with innovation often backfires.

Many domestic machine shops, characterized by relatively short processing cycles and a diverse range of parts, require an operator for each machine to manually handle tasks like part replacement, deburring, inspection, tool changes, regular maintenance, and error correction. Many companies with excellent lean management have very specific standard operating procedures for operators, such as carefully monitoring the machining state to prevent distractions, errors, and accidents.

However, even if the machining parameters are optimized and every employee performs flawlessly, it's impossible to exceed the limitations of the production equipment. Additionally, China's leading manufacturing companies are large-scale, well-managed, and have numerous employees. Managing and operating production systems of a similar scale overseas is challenging because foreign workers are not as easily directed as their Chinese counterparts. Therefore, before expanding internationally, it is essential to consider whether the automation level of the factory is sufficient, whether there is a need to employ a large workforce, whether the production scale can be reduced, and whether profitability is achievable without large-scale production.

Why must China’s manufacturing sector "involve" itself: comparing industrial involution to educational dynamics

The visible problems of "involution" only scratch the surface. The deeper issue is why "involution" occurs in China's manufacturing sector. Understanding the mechanisms behind "involution" reveals its more severe consequences.

The narrative of "extremely involuted Chinese enterprises going overseas to defeat once-dominant Western industry giants" is almost like a modern version of motivational stories, fitting well with traditional Chinese values. Historical tales like "Tie one’s hair on the house beam and jab one’s side with an awl to keep", "Borrowing light through chiseling walls", "Grinding an iron pestle into a needle", and "The foolish old man removes mountains" are prevalent. Leveraged by the solid foundation in mathematics and science developed through intense domestic competition, Chinese students often outperform their Western counterparts who might focus more on social life. Thus, many naturally believe that Chinese enterprises going overseas is akin to students studying abroad: the gauntlet of the college entrance examination forges the unyielding will and solid basics of Chinese students; and systems like last-place elimination and the 996 working hours mold Chinese enterprises into disciplined, battle-ready forces, poised to defeat Western giants overwhelmingly.

This conclusion that "extremely involuted Chinese enterprises will dominate overseas" is based more on the traditional Chinese virtue of enduring hardship than on logical reasoning.

The aim of involution: bigger companies garner more social resources

In manufacturing, lacking scale can mean difficulty in securing loans from banks. Conversely, once a company grows large, various resources begin to converge towards it, and local governments encourage leading enterprises to expand further, even directing local banks to provide low-interest loans. When a company becomes large and well-known, it receives protection from the government and society at large, akin to how fans protect their idols. In the domestic market, scaling up a business is highly enticing.

Even abroad, Chinese enterprises compete against domestic rivals

It is often reported that foreign countries conduct anti-dumping investigations on certain Chinese products. A persistent question arises: why do Chinese manufacturers not simply set their prices slightly lower than their competitors to secure higher profits? Instead, they often drastically reduce prices, leading to allegations of dumping. The reason is that even after entering international markets, Chinese manufacturers continue to face price competition primarily from domestic rivals.

Imagine this scenario: A foreign company prices a product at $100. China's Company A offers a similar product with high quality and cost-effectiveness at $90, making it highly competitive. Just as Company A is poised to secure the deal, Company B across the street offers a bid of $80. Although the profit margin is slim, with export tax rebates, new energy subsidies, and currency exchange gains, minus the annual expenses and some tax avoidance strategies, they still stand to make a profit by year-end.

As Company A contemplates matching the price drop, Company C in the town comes in at $70 and with inventory ready. As a local star enterprise with substantial equipment and large scale, Company C relies on volume for profits and maintains significant stock. Even if products do not monetize quickly and the factory operates below capacity long-term, the resulting costs are immense. Yet, even with pricing close to the cost of Companies A and B, Company C can survive.

While Companies A and B are debating whether to exit the market, Company D, which just built its headquarters in the city center, bids $60. With plans to go public, D needs overseas orders as a selling point and is determined to secure this project at all costs. Even if it means taking a loss to gain market presence, the loss can be recouped in the stock market within hours.

With Company D's disruption, Companies A, B, and C were contemplating exiting the market. At this juncture, the owner of Company E, located at the village entrance, made an entrance with a bid of $50, leaving everyone astounded as it was clearly a loss-making proposition. However, the owner of Company E had his calculations: rush to secure this large order regardless of the consequences, and with such a significant international project in hand, acquiring land and loans would be handled by the municipal committee and town leaders as part of a high-priority project. This would allow borrowing a substantial sum at low interest from local town banks, and securing hundreds of acres of industrial land in the development zone, with factory space almost given away for free. Half of these factory buildings could be leased out immediately, with real estate partners developing employee dormitories and residential buildings on the surrounding plots. Staff would be hired on the spot, poaching key technicians from Companies A, B, C, and D and finding operators locally. The cheapest second-hand equipment would be purchased—500 machines with only a 20% down payment. As for raw materials, payments could be deferred until customer payments were received. Once the project was completed, employees would be laid off, equipment sold, and factory space rented out. Suppliers could be further pressed for discounts under the guise of substandard quality. In the end, not only would cash flow remain positive, but substantial profits would also be gained from the surrounding real estate developments.

Although the scenario described above might seem dramatized, the reality of project operations can be even more outrageous. It also reveals the inherent logic behind low-price competition: to expand scale by any means necessary. Banks provide loans, policies offer support, and tax reductions become available only when the scale is sufficiently large. A sufficient scale grant negotiating power allows for the delay in payments to suppliers and enables the use of various social resources at lower costs. Due to its large scale, a company can further reduce costs and market prices, drive competitors out of the market, and increase its market share.

Enterprise involution: A result of having no other choice

Many industries have established entry barriers for private enterprises, objectively resulting in a situation where there are more competitors than available opportunities. The most lucrative orders in sectors like military, energy, and aerospace—often the most profitable—are typically secured (competed for) by state-owned enterprises. Private enterprises, at best, handle subcontracted work from these state-owned companies, which significantly diminishes their profit margins, and connections are often required to secure these orders.

Some local governments like to intervene even in industries where private enterprises are free to compete. This is manifested in their preferential support for certain promising enterprises. During times of overcapacity, they may order high-energy-consuming and highly polluting businesses to relocate and direct industry funds to high-tech companies deemed by experts to have potential.

While these actions may seem well-intentioned, they actually disrupt the rules of fair competition.

"Advanced class" model as a catalyst for involution

The political economy of Karl Marx teaches us that if a free market economy is left unconstrained, it ultimately leads to either monopoly or oligopoly. Market-dominant trusts can raise product prices, exploiting the masses when this happens. Capitalist countries have considered Marx’s views and consequently enacted anti-trust and anti-monopoly laws, as well as protecting SMEs to ensure that they are not unfairly treated in business activities due to their smaller size. In short, the strategy of most developed countries is to "support the weak."

Our industrial policy, on the other hand, focuses on "supporting the strong," providing greater support to industry leaders with the hope of building them into global business powerhouses. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore also adopted policies of supporting advantageous enterprises at the early stages of their economic development and achieved good results. However, this policy of supporting the strong creates a feedback loop: allowing the powerful to rapidly scale up like a black hole absorbing resources, with the side effect of making it impossible for smaller competitors within the industry to survive.

Thus, to gain favor from resource distributors, every company must do everything possible to scale up, and to achieve this, they must aggressively compete on pricing. The phenomenon of involution among enterprises and in education stems from the same cause. The main culprits are the resource distributors, which I refer to as the "advanced class model."

Baiguan: In China's examination-oriented education system, advanced class refers to a special type of class or course set up by schools to enhance students' exam performance. These classes provide a more focused and intensive learning environment and resources. Typically established within schools, advanced classes enroll students who have demonstrated superior academic performance. These classes aim to concentrate educational resources on high-achieving students to further improve their academic outcomes.

Schools create advanced classes to concentrate on talented students and pair them with the best teachers, aiming to improve the students' chances of attending top schools. This, in turn, enhances the school's reputation. Similarly, local governments pay special attention to promising enterprises within their jurisdictions, providing them with policy support and more resources, with the goal of helping them go public and boost the local economy. Over the past decades, this "advanced class" model has indeed stimulated local economies and nurtured many large companies. However, it has also exacerbated market distortions, making the strong stronger and the weak weaker.

The current industrial policy mirrors the "advanced class" model, leading to a situation where "the success of one results in the demise of many." This model favors the strong and neglects the weak, resulting in bolstering the strong at the expense of the weak and damaging the industrial ecosystem.

When a student becomes the hope of the entire school, or when a company becomes the nation's pride, the pressure can lead to psychological distress or foster arrogance and disregard for others. For example, a student who has been top of their class in the early years of high school and is seen as the hope of their family and school may experience a decline in performance in their final year. Not wanting to disappoint teachers and parents, they might resort to cheating. Similarly, some tech companies, in an effort to uphold their reputation as the pride of the national industry, may exaggerate their capabilities. Once their claims are proven false, the carefully crafted public image of the company collapses.

The strength of manufacturing lies in its industrial ecosystem: the health of this ecosystem depends on a diverse array of SMEs

Neglecting smaller players can also mean missing out on numerous opportunities. Many seemingly unremarkable enterprises actually harbor tremendous potential. Particularly in today's world, where global supply chains have become extremely complex and professional specialization increasingly refined, some specialized technical teams, often just a few dozen people, provide technical services to major global companies. For instance, I know of a small company that specializes in machine tool temperature simulation and control solutions; it has only about a dozen employees but serves dozens of industrial equipment companies in the vicinity. Since these equipment companies do not need to constantly perform temperature simulations, maintaining such a team internally is economically inefficient; however, this small team thrives by servicing multiple corporate clients. This type of business does not benefit significantly from scaling up, so being a regional small or micro-enterprise is sufficient. Modern manufacturing needs a large number of such small and micro-enterprises to provide specialized services for different projects.

The strength of manufacturing lies in its diversity. I have always disagreed with categorizing manufacturing and technology into high, medium, and low tiers. Technology is not about being advanced or outdated but rather about suitability. For example, developing film in the digital age seems obsolete, yet photolithography uses special developers. A technology that seems complex can often be broken down into several simpler technologies. Take the much-hyped high-end machine tools: no single technology alone can produce so-called high-precision machine tools. The components and control systems that make up precision machine tools are not mysterious; they can all be purchased on the market, or one could even hire an engineering consulting firm to help with the design, and no single supplier is irreplaceable.

Some technologies are indeed uncommon. For example, ordinary machine tool cooling devices need temperature control within +/-5°C, but high-precision machine tools require temperatures to be within +/-0.1°C, thus needing high-precision air conditioning. However, high-precision air conditioners are usually used in larger spaces like server rooms, hospitals, and workshops, where the requirement is only +/-0.5°C. The machining area of a machine tool is relatively small, so controlling the temperature within +/-0.1°C, although challenging for precision air conditioning manufacturers, is not insurmountable. The issue is that there isn't much demand for such specificity, which may be too trivial for large manufacturers to invest in R&D. Therefore, such niche market products are generally produced by small and medium enterprises.

The more SMEs there can produce industrial products that meet specific design requirements, the more diverse the manufacturing ecosystem becomes, thus enhancing the industry's stability.

Our take

The title metaphorically compares the "involution" in China's manufacturing industry to cancer. The analogy with cancer is apt because cancer cells have a high capacity for rapid replication, allowing them to expand quickly, much like how businesses rapidly scale up to capture market share. However, just as cancer cells harm the body's healthy cells and disrupt their orderly functions, ultimately leading to potential collapse, involution harms the healthy dynamics of the manufacturing industry.

The reason Chinese manufacturing enterprises are caught in "involution" is primarily because they aim to "scale up" through a strategy of low profits but high sales volume. This obsession with scaling up stems from two main factors: culturally and historically, China has encouraged diligence and endurance, advocating for the use of more labor and longer hours to compensate for technological deficiencies and catch up with the West. Secondly, government intervention has resulted in more resources flowing to large, leading enterprises, while the rights and interests of smaller companies are not adequately protected. The so-called "advanced class model" leads to involution, which in turn causes operational difficulties for small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises and contributes to the vulnerability of the entire manufacturing ecosystem.

A shift in laws and industrial policies is needed to break this vicious cycle—from "supporting the strong" to "supporting the weak." Participants in China's manufacturing industry, whether entrepreneurs or investors venturing overseas, need to keep a close eye on policy and industrial environmental changes. It is crucial to stay sharp - not only focus on large-scale and rapidly expanding enterprises but also consider the long-term sustainability of their competitive advantages and, importantly, not overlook investment opportunities in businesses with differentiated advantages in niche markets.