Pregnancy Tests Aren't Selling, But Sex Toys Are Booming

China’s New Consumer Trend - What This Means for Investors

(Disclaimer: not sponsored by any company mentioned.)

The Signal

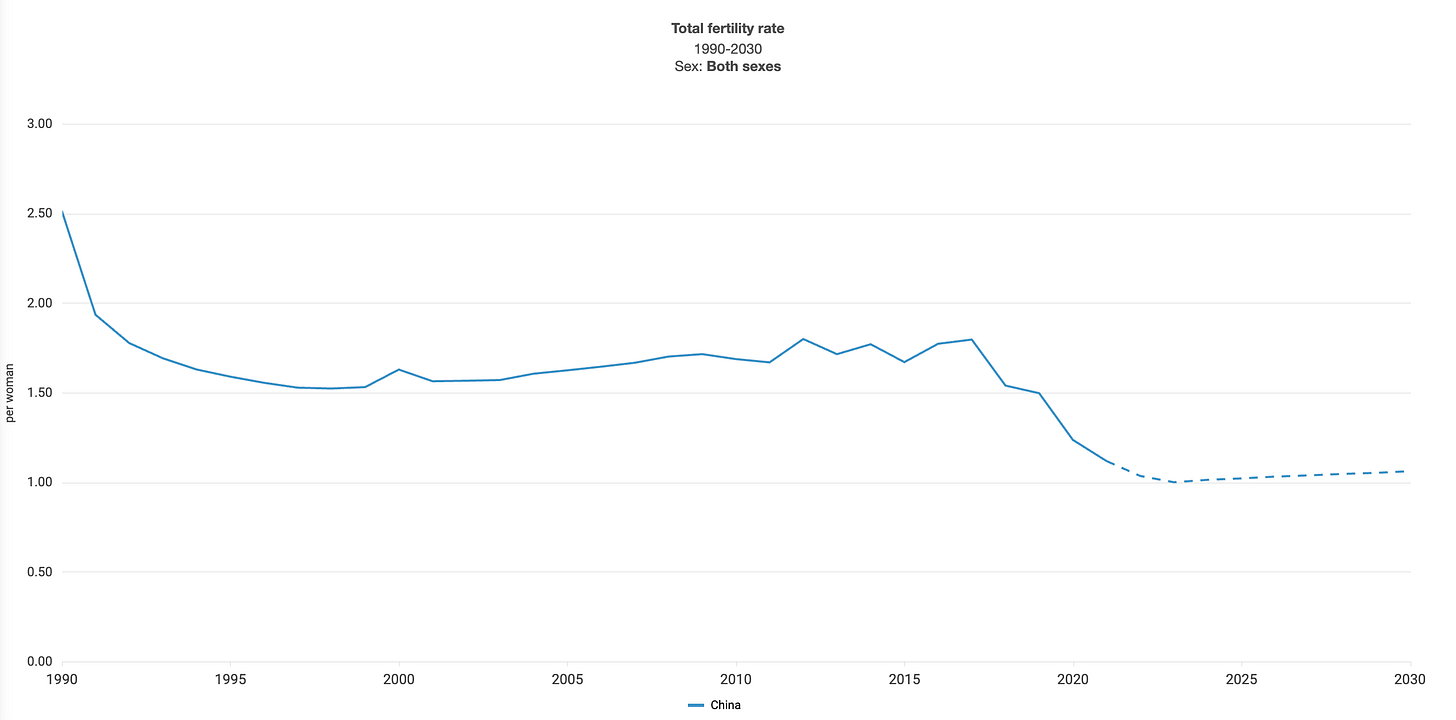

In the United Nations Population Division’s World Population Prospects 2024 (published approximately every two years), the numbers for China are stark:

China’s births are projected to fall to 8.71 million in 2025, down another 830,000 from last year, marking a new historical low. The total fertility rate is projected to drop to 1.02, barely above that of South Korea and ranking it second-lowest in the world.

For reference, the replacement level required to maintain population stability is 2.1—China is not even close.

Since the pandemic, China’s declining birth trend has effectively become structural rather than cyclical.

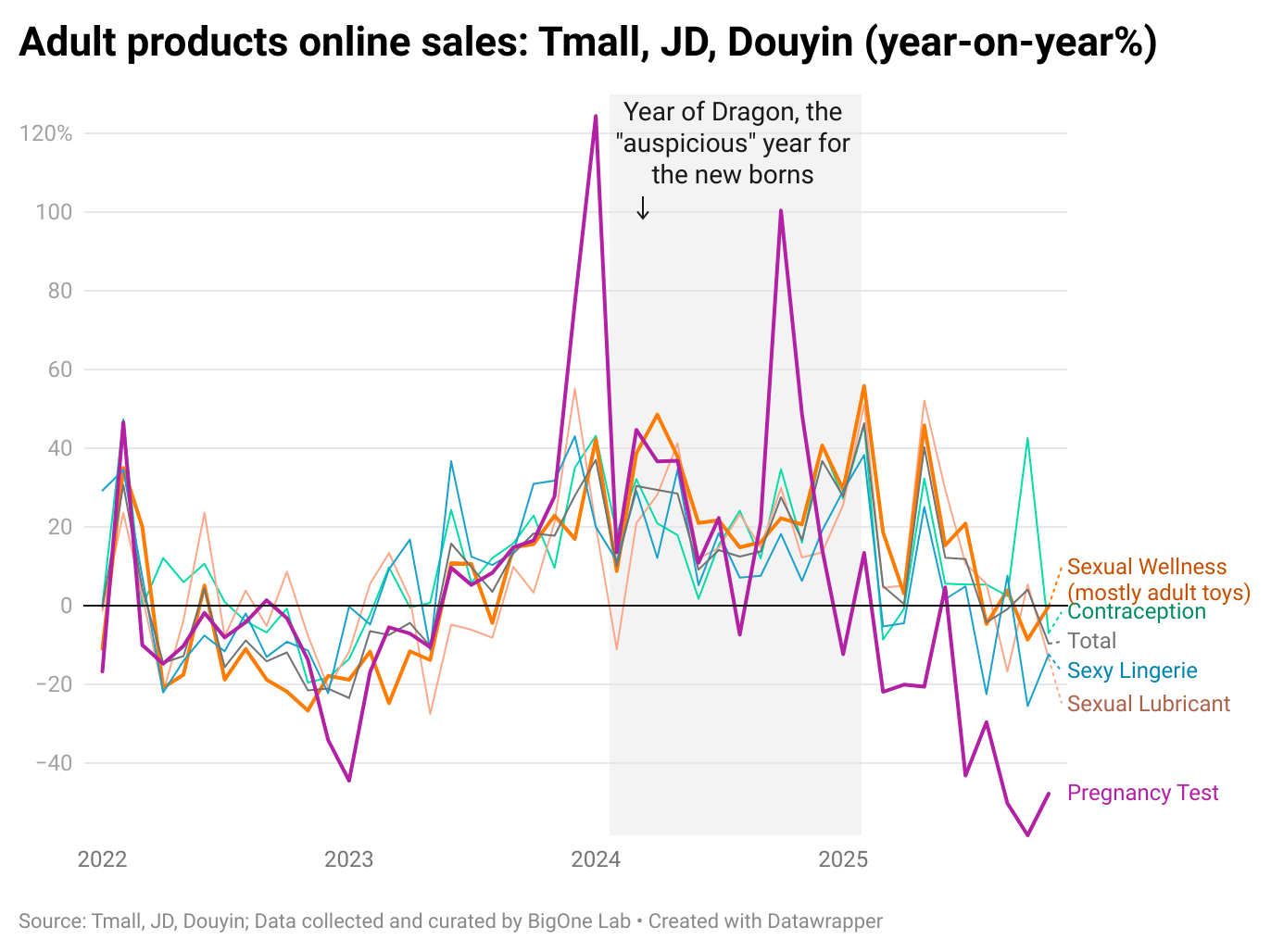

We see similar signals in our own data.

BigOne Lab, the parent company of the Baiguan newsletter, tracks online sales trends across multiple consumer categories. Sales growth of pregnancy tests peaked around 2024 and has been declining steadily since, with a noticeable acceleration in the second half of 2025. (2024 was the Year of the Dragon, traditionally viewed as an auspicious year for childbirth in China and usually associated with a temporary baby boom.)

The implication is clear: the outlook for births in 2026 and beyond is likely even weaker.

Low Fertility Is Not Simply a Function of Economic Development

China’s low fertility rate is not primarily driven by absolute income levels. The more important factor is the relative competitiveness of raising a child, especially when it comes to education and future opportunities.

Data from 2024 shows an interesting pattern: birth rates are higher in western and less-developed regions than in eastern, more developed ones:

Tibet ranks first with a birth rate of 13.87‰, followed by Ningxia, Guizhou, Qinghai, and Xinjiang (all above 10‰). Guangdong, at 8.89‰, ranks seventh and is the highest among the more economically developed regions.

By contrast, Shanghai is at only 4.75‰, Jiangsu at 4.98‰, and Beijing at 6.09‰; all of these are among the wealthiest areas in China.

A common question is:

If China was far poorer after the founding of the PRC, why were families still willing to have many children—to the point that population control policies became necessary? And why, now that people are materially better off, are they reluctant to have children?

The answer is simple: relative comparison matters more than absolute conditions.

Today’s childbearing-age adults—mostly born in the late 1980s and 1990s—grew up as only children. In many households, virtually all family resources were concentrated on a single child. That level of intensive investment became the internalized “baseline.”

In economically advanced regions, parents aim even higher. Even if their absolute living standards are already very high, raising a child increasingly feels like entering a nationwide—or even global—competition for elite education and future prospects.

As expectations rise, so do perceived costs, pressure, and social comparison.

More importantly, in these regions where career upsides are higher, the opportunity cost of pregnancy and raising children for women is also significantly higher.

Therefore, behind China’s declining fertility rates lies a widening chasm in both economic development and social mindsets. Although they belong to the same nation, certain Chinese regions now effectively mirror the living standards—and the demographic challenges—of developed economies, while other regions remain at a vastly different stage of development.

What This Means for Investors and the China Consumer Market

So, what are the implications of these trends for investors and observers of the Chinese consumer market? Here are a few of my takeaways: