The world tastes the sweetness of US-China decoupling

A cautionary tale for China

The following article is a translation of a recent article by Bob Chen, a macro-economist and venture capitalist, on his WeChat blog 嬉笑创客. By now you may be already familiar with Bob, whose review of China’s “go global” opportunities has been one of our most popular podcast episodes.

In this article, Bob made a series of bold observations. He has pointed out that the rest of the world not only stands to benefit from the US-China decoupling, but armed with know-how from Chinese people themselves, they may actually succeed in realizing that benefit. The analysis at the end of the article on how China has ended up in this situation is also among the most succinct yet insightful takes our team has seen.

The decoupling of China first allowed the US to taste the sweetness. Domestic manufacturing and chip investment have been increasing day by day in the US, driving employment. While the equipment industry is also flourishing. Several inland states in the United States have come forward to attract investment, promoting an investment promotion system similar to China's policies.

A U.S. legislator can easily propose a nonsensical proposal and bring down a leading Chinese pharmaceutical company with a market value of hundreds of billions, showing their international influence to the voters. Not to mention the resurgence of Trump. All of which made the Chinese stock market the sole loser globally.

U.S. manufacturing investment has surged. After the determination to decouple, it has begun to reverse the process of deindustrialization over the years—and has also chosen to go all in on high-end manufacturing:

U.S. engineering machinery giant Caterpillar and other companies have also ushered in a spring; correspondingly, even a proposal put forward by a US House committee with a very weak legislative record can scare to death WuXi AppTec, a biotech company dependent on foreign demand.

More dangerously, the rest of the world has also tasted sweetness from decoupling from China. With the decoupling of China and the United States, Southeast Asia, Mexico, and India have not only welcomed a large amount of Western investment but also a large number of Chinese entrepreneurs. Everything is done to avoid tariffs and potential risks. Even though there is already overcapacity domestically, the domestic demand is too weak, so they must follow external demand and build production capacity overseas.

Baiguan: please refer to a previous podcast episode regarding the adventures of an account of a Chinese entrepreneur bringing know-how and expertise overseas:

#4 The adventure of a Chinese entrepreneur in the Belt & Road countries

About Today’s Episode In today's episode, we have a very special guest, my friend Yipeng, a seasoned entrepreneur from China. He has built an impressive global business. His incredible 15 years of journey, perfectly reflect the evolution of China's business community in the past decades.

The economic imperative is more effective than any policy incentive.

Originally, the global supply chain was closely integrated, and everyone felt that no one could do without each other. Later, Europe took the lead in decoupling from Russian energy, and it turned out they were not frozen to death because of this. Instead, U.S. oil production and exports reached new highs.

With this lesson in mind, entrepreneurs, talents, and capital have become bolder in decoupling. The U.S., by leading the way, has driven a host of smaller countries to decouple, and it seems that inflation is also receding. Whether to decouple or not, Chinese companies are still doing everything possible to export China's surplus production capacity and inexpensive goods, contributing to lowering global inflation on the one hand and desperately squeezing the profit space of domestic suppliers, keeping manufacturers at the marginal cost line for subsistence.

Many emerging market countries have also benefited from the decoupling. They adapt to outsourcing from friendly shores, invest in production capacity, and use investment to drive their own GDP. Each country dreams of reliving the glory of China's reform and opening up.

We often say that no country can replace China, and the next China is still in China. But if the young population of India and Southeast Asia, the geographical location of Mexico, and the wisdom of Chinese entrepreneurs gather together, a brand-new supply chain structure will take shape.

If people find that enduring short-term pain is better than enduring long-term pain, and a ready-made path and a golden opportunity are right in front of them, what reason do people have not to work hard and replace China?

The outstanding rise of stocks in emerging markets is just a sign.

When a whale falls, all living things thrive一鲸落,万物生.

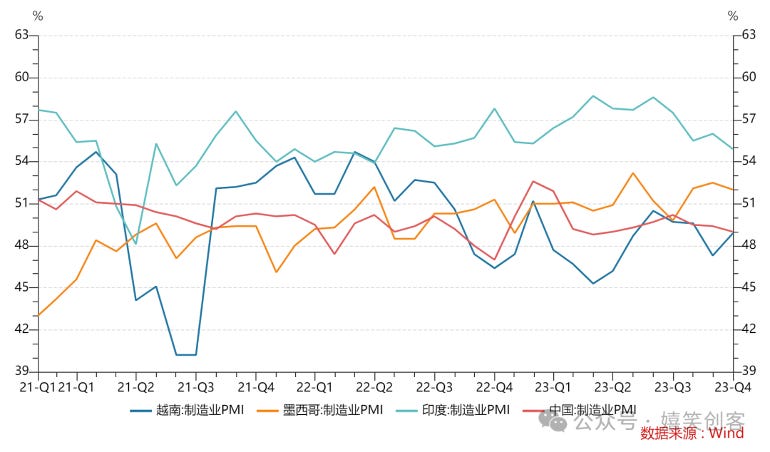

Foreign capital flows to Mexico, India, Southeast Asia, and other countries are all increasing. I track the manufacturing PMI of major economies every month. In 2023, I found a strange phenomenon. In the past, when the U.S. dollar index rose, it often meant a decrease in risk appetite and capital outflows. But last year, except for a decline in Vietnam, the manufacturing PMI of India and Mexico performed well, forming a contrast with China.

It used to be said that Southeast Asia and Mexico lacked industrial clusters and could only undertake low-end, labor-intensive work. But don't forget that at the beginning of the Reform and Opening up, Japan, South Korea, and even our compatriots in Taiwan and Hong Kong also saw us in the same way. Now that our demographic dividend has entered a period of decline, is there any reason to underestimate the young and strong population [in other places]?

Lack of industrial clusters and lack of components [in those new places] may be a reality, but today's long-haul transportation and cross-border logistics are already developed enough to gradually move production capacity. Even if you are occasionally unable to source parts, which may delay technological upgrades, Chinese entrepreneurs themselves also go abroad, carrying with them the entire knowledge and know-how. If innovative production lines can’t be moved, why can’t they move the repetitive ones? Equipment is not an obstacle. The only difficulty is that Vietnamese workers may want to leave work on time and sit in a circle in the city square to drink coffee, or Mexican workers want to return home earlier for dinner. But is it possible that we are the ones who do it in the wrong way in the first place?

Can we continue to deceive ourselves?

A recent research report by a certain brokerage firm, "The Powerless Decoupling," believes that since decoupling, China's share in global exports has actually increased, and the share of Chinese inputs consumed in U.S. production has also been rising.

However, upon closer examination, the first phenomenon can only reflect 1) that countries deeply decoupled from the world, such as Russia, are more dependent on now China, and 2) “passing-through” trade through third-party countries in order to avoid trade restrictions. In those “passing-through” trades, third-party countries not only took a cut of the profit, but a permanent transfer of production capacity in the future also can’t be ruled out.

The second phenomenon only extends to 2020—the peak of China's exports—without accounting for the trend in the past two years.

Even if only labor-intensive industries are transferred overseas, how many of China's 1.4 billion people can be absorbed by high-end production capacity? Can our education system and market restrictions support a large number of high-end jobs? With weak domestic demand and low wages in the service industry, the more emphasis we place on high-end manufacturing, the greater the impact there is on employment. The more employment is affected, domestic demand will become even weaker, leading to a greater degree of production capacity being driven by external demand.

Yet, overseas residents have tasted the sweetness of the decoupling. This is very dangerous.

From the perspective of overseas residents, the hardworking residents [Baiguan: referring to Chinese manufacturers] who used to produce for the world have been suppressed, and the whole world has to support a “new world factory”. Because the original working residents are too hardworking and too capable, they become over-competitive so their own profits are squeezed out. But the “new world factory” is more decentralized, people are more relaxed, and demand a better work-life balance.

What will be the economic consequences?

In the short term, It seems that everyone will endure a temporary decline in output efficiency. But the pie that originally belonged to one will be divided among many, and labor will get a larger share of the pie. The 300 million Chinese middle-class people could be replaced by the future middle class of a billion people in emerging markets worldwide. This is actually quite good for everyone [except for China]!

More importantly, we can't say anything about it. After all, we are the advocate of the Belt and Road Initiative, posing as the leader of the emerging world. Now that this posturing has become a reality. We are really practicing what we preach now.

As for production efficiency, will it really decline? it's actually hard to tell. If there is serious overcapacity, even the pains of transition will be relatively light.

Concurrent with this economic change is the change in global discourses.

The right-wing movement surging worldwide. The first thing Milei did after taking office was to sing a different tune with us, so our media rarely reports on Argentina now. If Trump comes back to power, we will once again usher in a new round of deregulation and protectionism.