The comeback of the "national enterprises" pride

"Chinese national enterprises"—the so-called 民族企业—have long been a staple of China's history textbooks. In modern Chinese history, they are remembered as heroic businessmen and entrepreneurs who thrived amid the chaos of the late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China era, as well as during World War II.

In recent years, however, the term "Chinese national enterprises" has resurfaced with new layers of complexity. Nationalism has evolved beyond mere political propaganda and into a powerful business strategy. For today's companies, being recognized as a "true Chinese national enterprise" can win both the hearts and wallets of consumers. But one misstep can spark accusations of being unpatriotic, leading to devastating boycotts.

This is the new reality of China's consumer landscape—something I explored in last year's newsletter, Nationalism in China: A business strategy over political discourse.

The problematic green card, foreign passports, and second-generation elites abroad

Following China's decades of rapid economic growth, it became common—almost standard practice—for successful entrepreneurs and affluent families to obtain foreign green cards or passports, most notably from the United States and Canada. It also became standard practice for business leaders to send their children—the so-called second generation—to study abroad, with the U.S. and Canada again being top destinations.

These were as much personal choices as strategic ones. For companies seeking global markets or planning to IPO overseas, registering in the Cayman Islands was considered a standard step for accessing foreign capital markets.

But in today's charged social atmosphere, these once-routine practices have become dangerous liabilities. Some consumers now question the national loyalty of business owners. A foreign passport or offshore holding company can be twisted into damning "evidence" of betrayal. Whether a company is a true "Chinese national enterprise" carries far more weight today than ever before.

For instance, Dong Mingzhu, Chairwoman and CEO of Gree (SHE: 000651), one of China's proudest home appliance brands, recently declared that Gree would no longer hire anyone who has studied or worked abroad. During Gree's April 2025 extraordinary shareholder meeting, she stated bluntly:

"Gree will never hire returnees (海归)—some of them are spies, and I don't know who is and who isn't."

Although her comment was quickly dismissed by state media, including People's Daily, the fact that such a bold statement came from the head of a publicly listed "national pride" brand speaks volumes about today's shifting social climate.

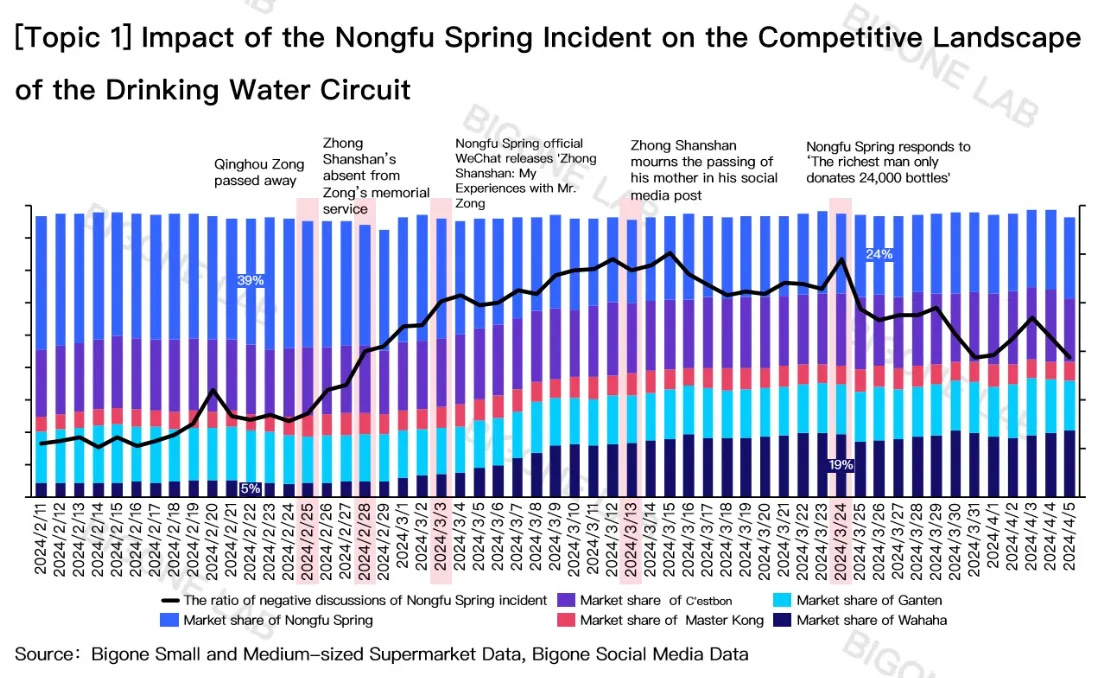

You may recall the nationalist backlash that hit Nongfu Spring (9633.HK) last year. One of China's largest bottled water brands found itself at the center of a public firestorm after netizens accused its "Oriental Leaves" green tea packaging of containing Japanese cultural elements—a vague but emotionally charged claim.

In March 2024, online nationalists accused the packaging of "Oriental Leaves," a green tea beverage by Nongfu Spring, of containing Japanese elements and being "unpatriotic" and pro-Japanese.

Things escalated quickly when people began questioning whether the founder's son held U.S. citizenship. Despite the company's efforts to assert that "Nongfu Spring will always be a Chinese company," the damage was done. (I wrote about this incident in last year's newsletter here.)

Boycotts followed. Netizens accused the company of being a "traitorous enterprise" that was "sending money to Americans"—phrases that went viral during the scandal. According to supermarket panel data we track, Nongfu Spring's market share materially declined after the crisis.

Ironically, it was during this period that Wahaha, a longtime rival, rose as the patriotic alternative. The company gained rapid market share and was hailed as the "true Chinese choice."

But who would have thought that in less than a year, Wahaha would find itself in an eerily similar PR disaster?

The Wahaha family dispute

Just like Nongfu's founder, Wahaha's late founder Zong Qinghou was also from Hangzhou, long celebrated for his modest lifestyle. Known as the "billionaire in cloth shoes," he famously wore simple black clothes, flew economy, and reportedly spent under ¥50,000 yuan (~7000$) a year.

But following Mr. Zong's passing in February of last year, his private life—and immense offshore wealth—was exposed in a dramatic family dispute.

On July 12, 2025, three children born out of wedlock to Wahaha Group founder Zong Qinghou—Zong Jichang, Zong Jieli, and Zong Jisheng—filed parallel lawsuits in the Hong Kong High Court and Hangzhou Intermediate People's Court. They are seeking to divide a 29.4% stake in Wahaha Group and approximately $2.1 billion in offshore trust assets previously held by the late Zong. The total value of the disputed assets is estimated at RMB 35 billion (around $4.8 billion).

Court documents revealed a web of luxury real estate and global holdings, shattering the image of Zong as a humble entrepreneur. More controversially, it was discovered that his chosen successor, daughter Zong Fuli, had held a U.S. passport for years and had used it to buy property in Hong Kong in 2009 under the name Kelly Fuli Zong.

Although official records show that she renounced her US citizenship in 2010, the revelation still touched a nerve among many Chinese netizens. Under Chinese law, dual citizenship is prohibited, and the exposure of the Zong family's privileges clashed with the public's long-held perception of Wahaha as a national brand for the 'common people.'

Netizens finally realized that the supposedly frugal billionaire actually had a complex family and enormous wealth overseas — the public persona of a modest, patriotic entrepreneur had collapsed.

While many netizens indeed support Zong Fuli for her recent leadership and philanthropic initiatives—such as donating ¥100 million to establish a food science school at Xi'an Jiaotong University—many still feel disillusioned. Comments like "Turns out the whole family is American" and "Wahaha is sending money to America" began to circulate—ironically echoing the same language once used to attack Nongfu.

Suddenly, the company that benefited from a nationalist backlash was facing the same scrutiny.

Although it is nonsensical to judge whether a company deserves support solely based on the nationality of its core management or where it is registered, nationalism remains a powerful reality for many Chinese people today—not everyone, but certainly a sizable portion of the population.

These sentiments are already having real impacts on businesses. On social media, nationalism is one of the most traffic-generating topics, sustaining countless content creators—many of whom lack genuine patriotic conviction and simply prey on consumer sentiment. But in a country of over 1.4 billion people, even a small fraction of maliciously deployed nationalist sentiment can inflict outsized damage on companies and public figures.

Public sentiment dynamics

So what impact has this latest crisis had on Wahaha's business—and that of its peers like Nongfu Spring (9633.HK)? Have we seen a repeat of last year's market share collapse?

We've analyzed millions of social media posts to trace the trajectory of online sentiment, as well as offline sales up until July 22 — and here are our preliminary findings on the evolving public opinion: