China’s ageing population is no longer a forecast—it is a fact. Yet the true size of the silver market, and the real commercial upside, still hinges on one variable: the seniors themselves.

China is already a mosaic of regional, urban-rural and generational fractures—themes we have dissected in earlier pieces: my firsthand experience of the country’s overstretched healthcare network, a deep dive into the historic roots of the rural–urban chasm, a data-driven map of opportunity gaps across city tiers, and our long-running China City column that puts faces and numbers to the so-called lower-tier markets.

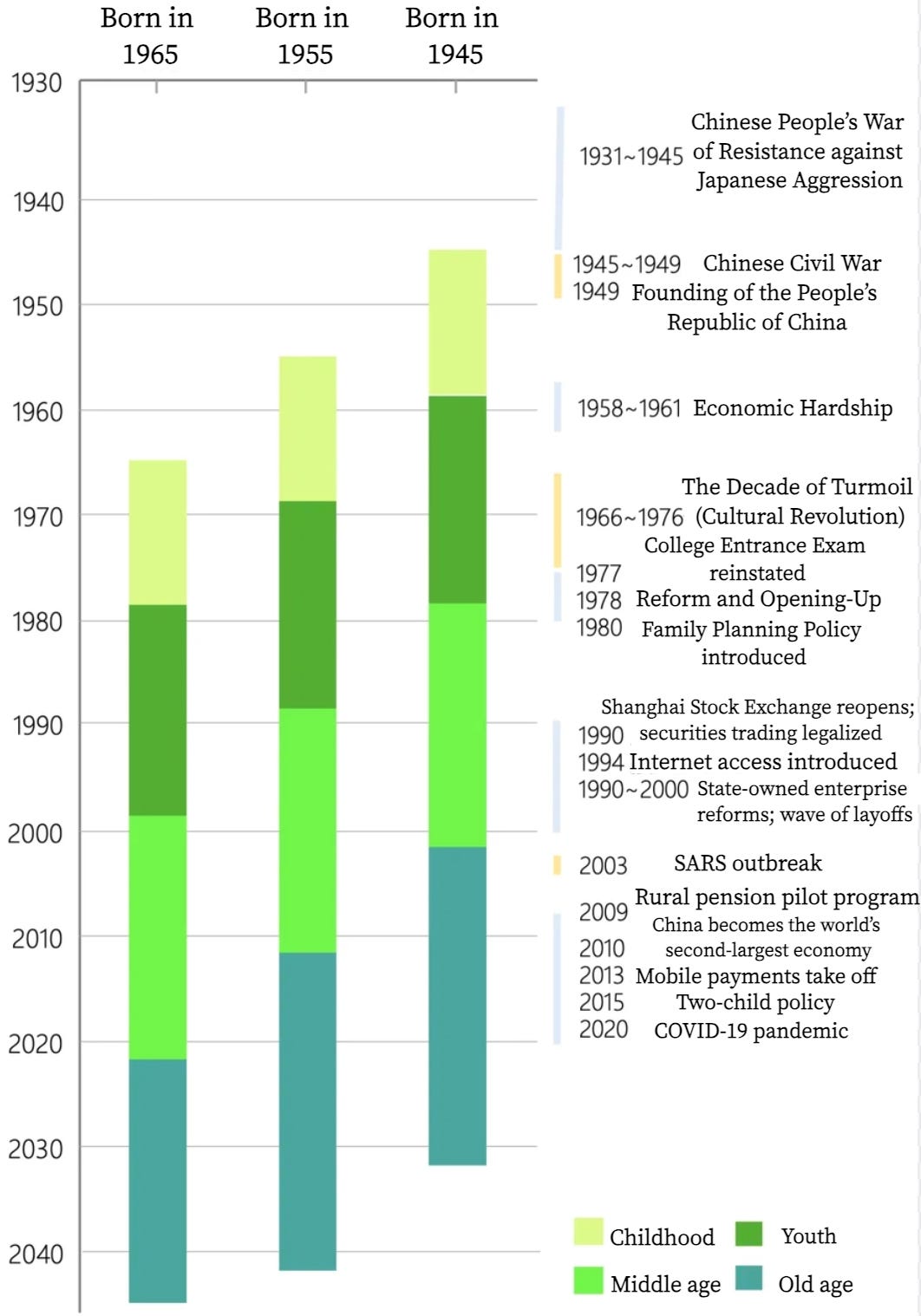

However, inside the 60-plus cohort, the fractures run even deeper. A mere ten-year birth spread can separate childhoods of famine from adolescence in the reform era, producing polar opposite life stories, values, and wallets. Who these people really are is the first due-diligence question any serious player must answer.

In today’s post, we distill a tour-de-force report by Cyanhill Capital (an early-stage investment firm focusing on the consumer sector) that maps China’s elderly in high resolution—their micro-segments, unmet needs, and the products and services already whispering profit.

Below is Baiguan’s translation of the original article (some paragraphs are abbreviated or redacted):

China’s most fragmented generation of seniors

Sampling bias is not an abstract statistical concept but a daily illusion. Focus on tech-savvy retirees with money and time, and you see a booming “silver economy.” Study only nursing homes, and the narrative becomes one of medical dependence and long-term care. Hand out surveys in community centers, and the conclusion is that seniors are socially active. The spotlight shows vitality; the shadows are filled with silence.

Countless silver economy reports inflate perceptions of elderly spending power by focusing on high-visibility samples, while sidelining the broader majority as noise. At Cyanhill Capital, we see people as the fundamental variable in consumption, not just data points. Our research finds that China’s current senior generation is far more fragmented than widely assumed. Compared with earlier and later cohorts, they show the greatest internal heterogeneity—arguably the most complex and divided generation in modern Chinese history.

Consider this: Aunt Li, 60, has never shopped online, while Uncle Wang, 80, has joined the ranks of livestream sellers. Among today’s 70-year-olds, some travel the world annually, while others have never left their hometown. Some struggle to use a smartphone, while others command millions of followers on social media with content like “A Day in the Life of a High-Energy Senior.” If one were to give this generation a single label, what could it possibly be?

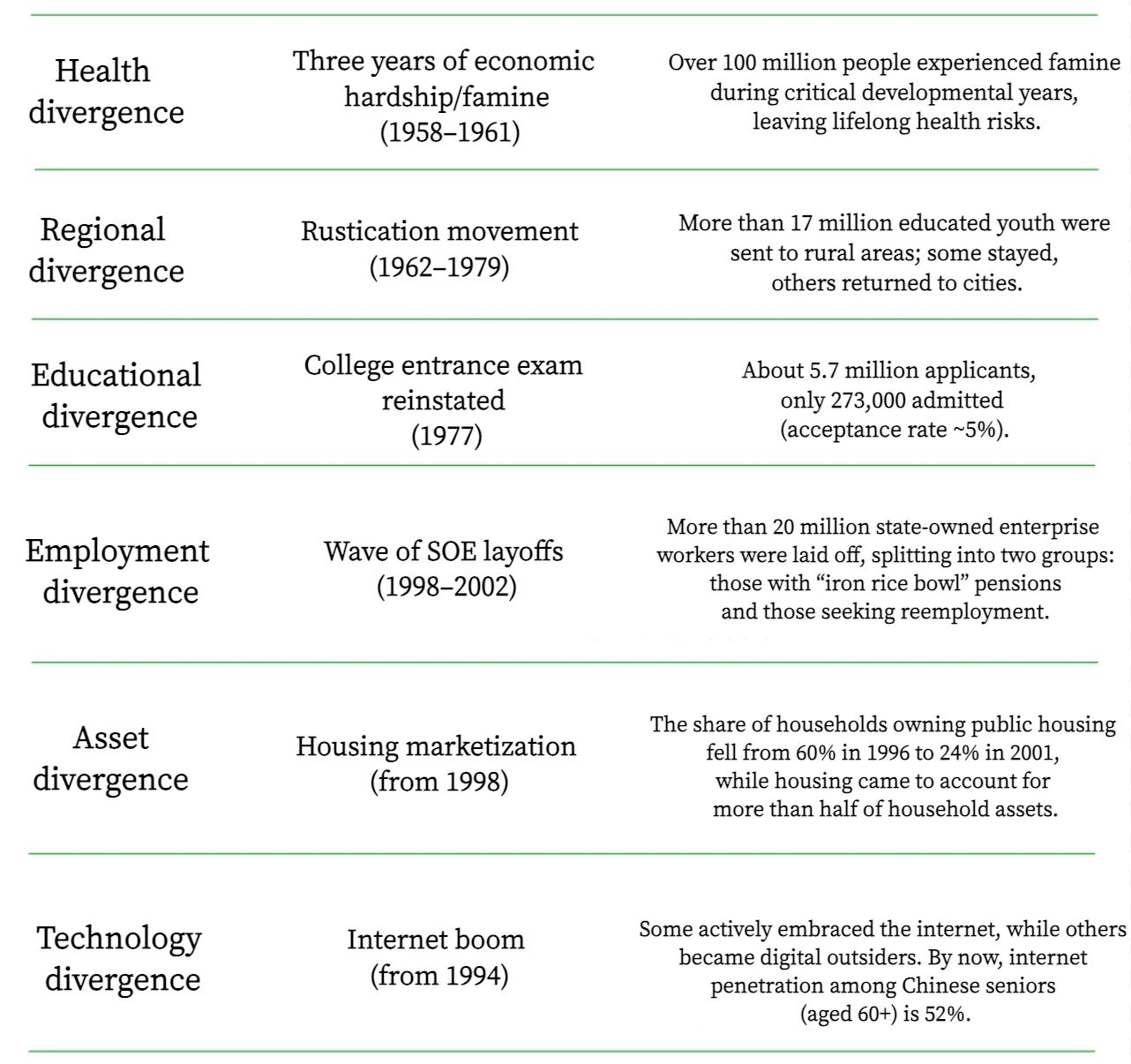

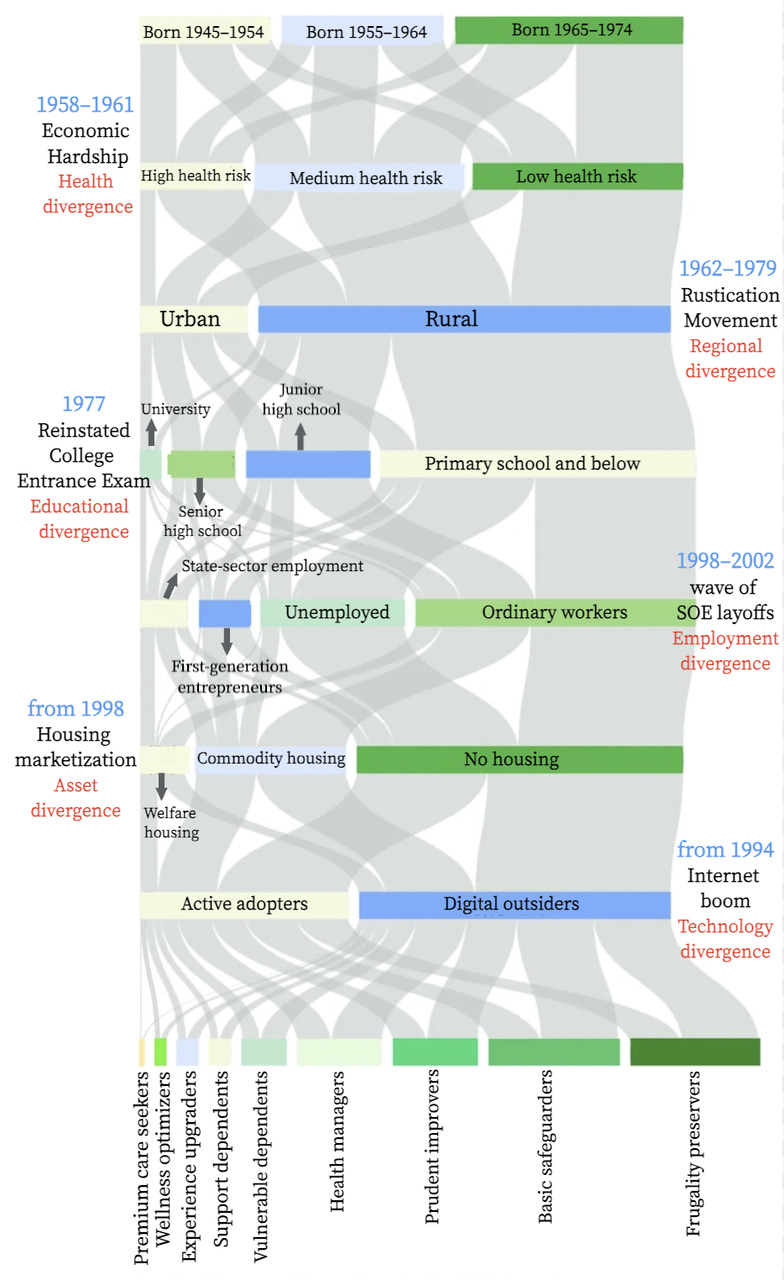

The heterogeneity within generations is not unique to China, nor is it exclusive to the elderly. But what sets China’s current seniors apart is the unprecedented structural complexity born of rapid social upheaval and institutional ruptures. This has made them the most heterogeneous and fragmented generation in the country’s modern history.

A closer look shows that different age cohorts in China were shaped by profoundly different circumstances. Take the post-1950s cohort: as children, they endured the Great Famine, carrying lasting memories of hunger through their formative years. In adolescence, their schooling was interrupted by the Cultural Revolution. At an age when they should have been applying their knowledge and skills, they were sent to the countryside for “re-education” through manual labor. Many missed out on the economic dividends of China’s later boom simply because they lacked access to formal education.

By contrast, the post-1960s cohort came of age in a very different world. They benefited from the reinstatement of the college entrance exam and the rapid expansion of education. Their youth coincided with the early years of reform and opening, full of energy and opportunities. By middle age, they had experienced soaring property prices, volatile stock markets, the rise of the internet, and widening wealth gaps. The difference between these two generations is not one of degree, but of kind—a qualitative rupture rather than a quantitative stretch.

On top of this generational divide lies a deeply entrenched income disparity, stemming from long-standing gaps between urban and rural residents, government and public-sector employees, corporate workers, and those covered under the basic resident insurance scheme (Baiguan note: Last August, Baiguan posted an article named “How did China’s urban-rural divide emerge?”, expaining the origins and consequences of the dual urban-rural structure in China). According to estimates from the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, and the National Bureau of Statistics, among nearly 300 million retirees:

About 20 million are former government and public-sector employees, roughly 5% of the total, with average monthly pensions of RMB 6,243.

Around 120 million are retired corporate employees, making up 40%, with an average monthly pension of RMB 3,271.

Some 170 million are covered under the urban and rural residents’ basic pension scheme, accounting for 55%, with average monthly payouts of just RMB 223.

In effect, public-sector retirees earn pensions that are 28 times higher than rural residents, while corporate retirees receive 15 times more—a gulf that has left enduring fault lines across China’s elderly population.

China’s seniors: complexity shaping divergent consumption patterns

Differences in education, career trajectories, family structures, urban–rural environments, and health conditions have created unprecedented diversity in values, behaviors, and everyday choices among China’s elderly. Nowhere is this heterogeneity more visible than in consumption.

For some, spending is a way to maintain social connections; for others, it serves as compensation or emotional comfort. And for many with limited resources, consumption is reduced to meeting only the most practical needs. Understanding these internal divides is the first step toward analyzing their most direct extension—consumption patterns.

The “high-visibility samples”

Unsurprisingly, the most affluent and capable seniors dominate the consumption narrative. With high willingness and capacity to spend, they have become the most visible representatives of China’s silver economy under the gaze of both markets and capital.

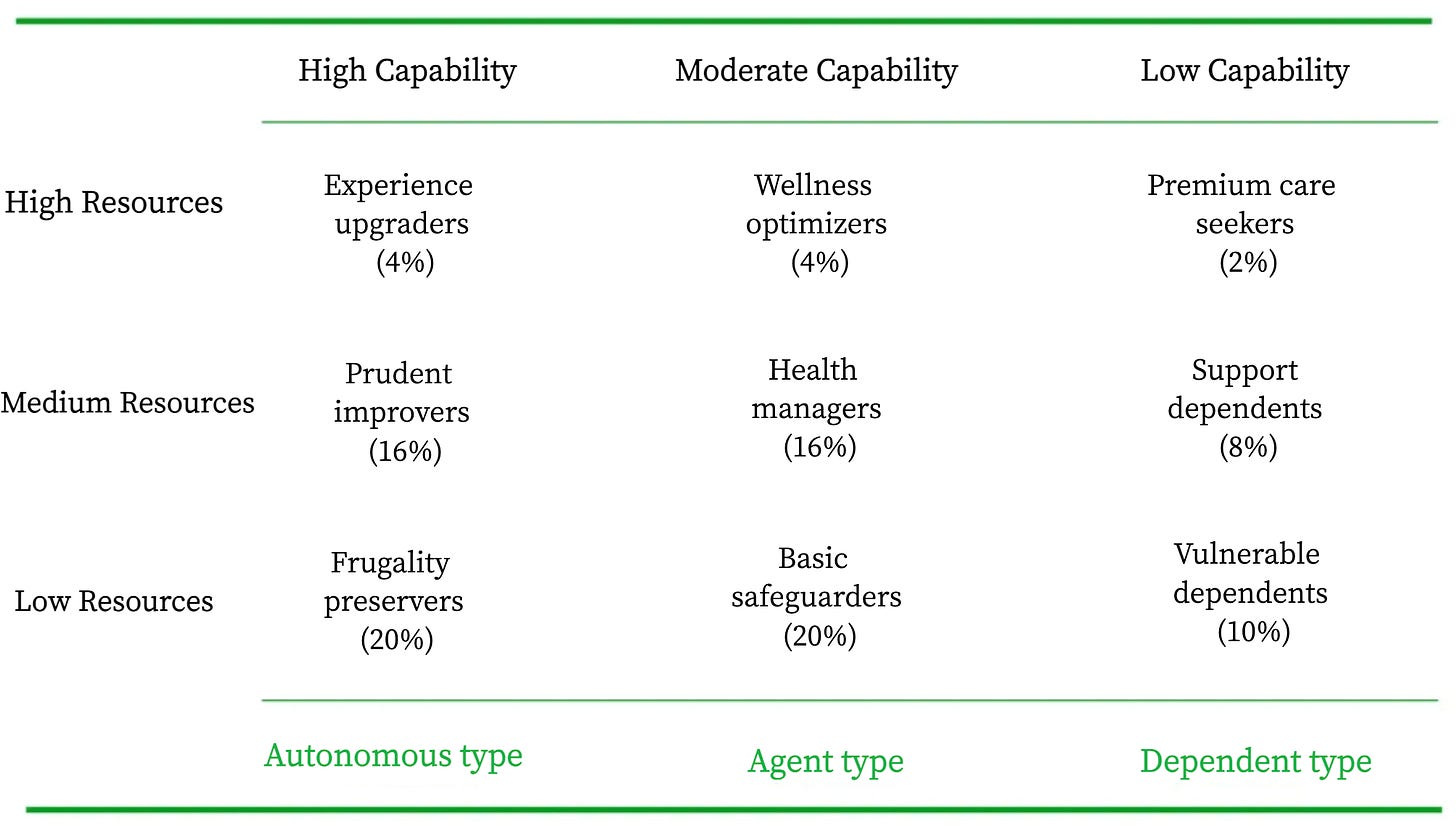

Experience upgraders: high resources × high capability

This group typically enjoys strong financial security, good health, and high digital literacy. Many retired from lucrative industries or senior government posts, with generous pensions, multiple homes, and sizable financial assets. With little dependence on their children, they view retirement as a “second life,” marked by quality and differentiated experiences. Their spending focuses on premium travel, private clubs, and smart wearables.

They are the high-spending core of China’s senior travel market, favoring wellness tours, customized itineraries, and outbound trips. Their average spending far exceeds that of the typical elderly traveler, making them central to the “upgraded silver tourism” trend and fueling the growth of adjacent sectors such as wellness real estate and medical tourism.

Socially, they seek to rebuild networks through exclusive clubs—spaces that represent not just hobbies, but continuity of identity and reproduction of social capital. Preferred options include high-end, membership-based groups such as calligraphy societies, wine salons, and golf clubs.

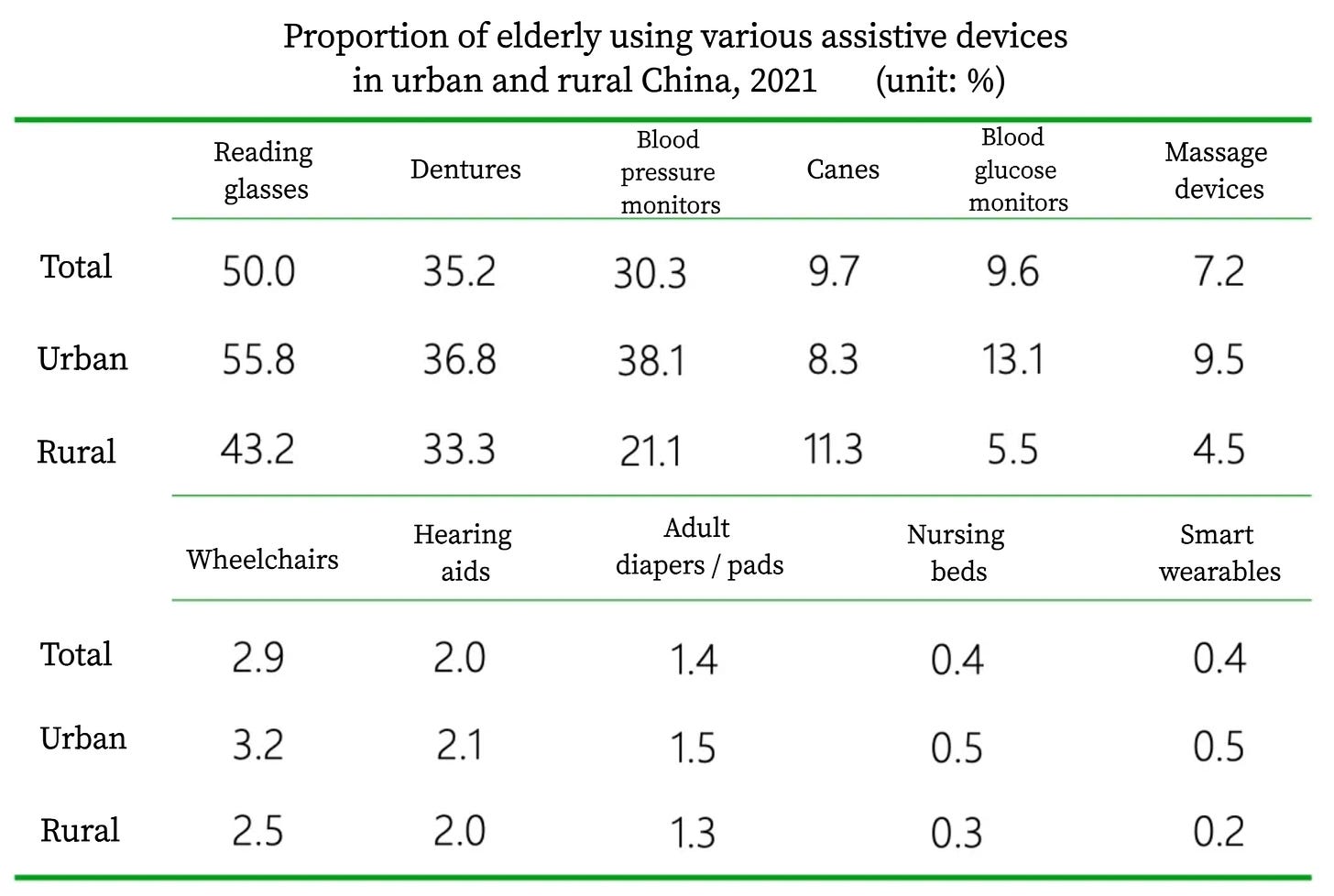

Digitally adept and health-conscious, they are also among the few seniors driving demand for smart wearables. Data shows that such devices account for only 0.4% of total elderly assistive products in China, reflecting their rarity and high adoption barrier. Within this niche, experience-driven seniors lean toward international or premium domestic brands, with purchases motivated as much by health monitoring as by status signaling—often in tandem with spending on fitness and travel.

Wellness optimizers: high resources × moderate capability

This group is wealthy but constrained either by a weaker physical condition or lower digital literacy. Many suffer from chronic illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, or heart disease, or live with suboptimal health. Cognitive and learning abilities often decline with age, further shaping their choices. Unlike the “experience upgraders,” their spending revolves around health and care services. They are willing to pay premiums for peace of mind, making them the core consumers of high-end supplements and professional caregiving.

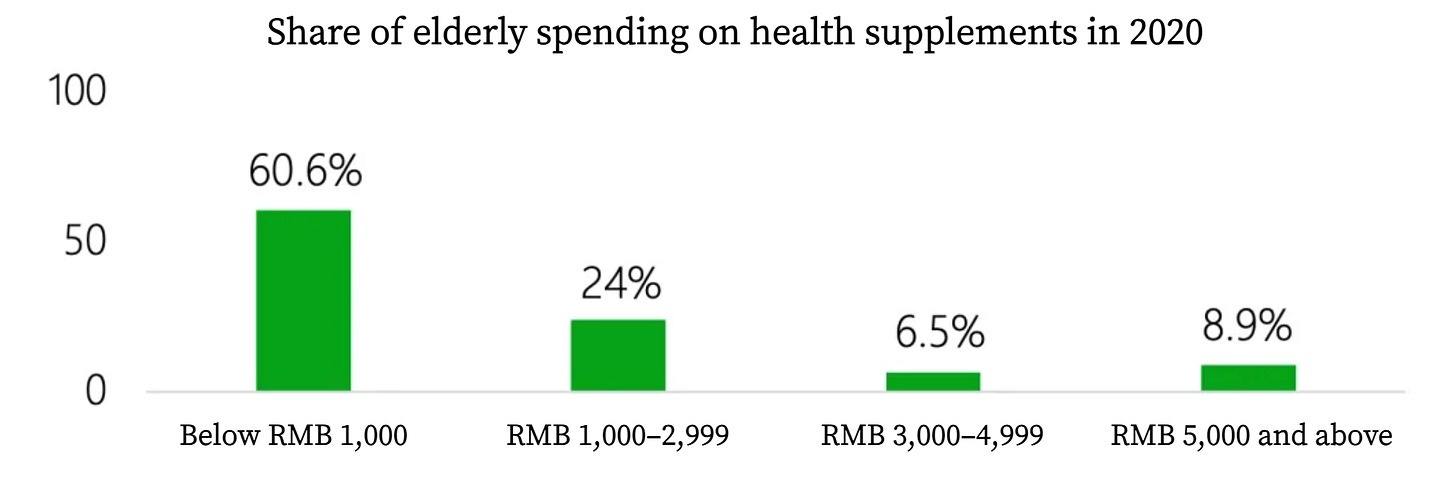

Chronic illness and health anxiety sustain their demand for healthcare. They favor large brands, imported products, and high-priced supplements, with annual spending typically ranging from RMB 3,000 to 10,000—far above the average. According to the Fifth National Survey on the Living Conditions of Urban and Rural Elderly in China, only 16.6% of seniors consume health supplements, and just 8.9% spend over RMB 5,000 annually—concentrated within this segment.

As their physical capacity declines, daily chores and personal care become burdens. To reduce pressure on their children and safeguard quality of life, they turn to professionalized services, from live-in caregivers to specialized nursing staff and home-service providers. They demand high-quality service and are among the few willing to pay a premium for reassurance. A 2022 report by the China Consumers Association found that only 27.8% of seniors had used household services such as cleaning, and just 22.5% had accessed chronic disease or rehabilitation care. Those who did were disproportionately high-income.

Prudent improvers: moderate resources × high capability

These are China’s urban middle-class seniors. With pensions of roughly RMB 3,000–4,500 per month, stable housing, and financially independent children, they enjoy relatively good health and strong self-care abilities. Many are digitally literate, comfortable with WeChat, e-commerce, and short-video platforms. Their consumption mindset is conservative but aspirational: they avoid extravagance but are willing to pay for steady improvements in quality of life. Core spending goes into culture, leisure travel, and home upgrades—making them the backbone of the senior consumption market.

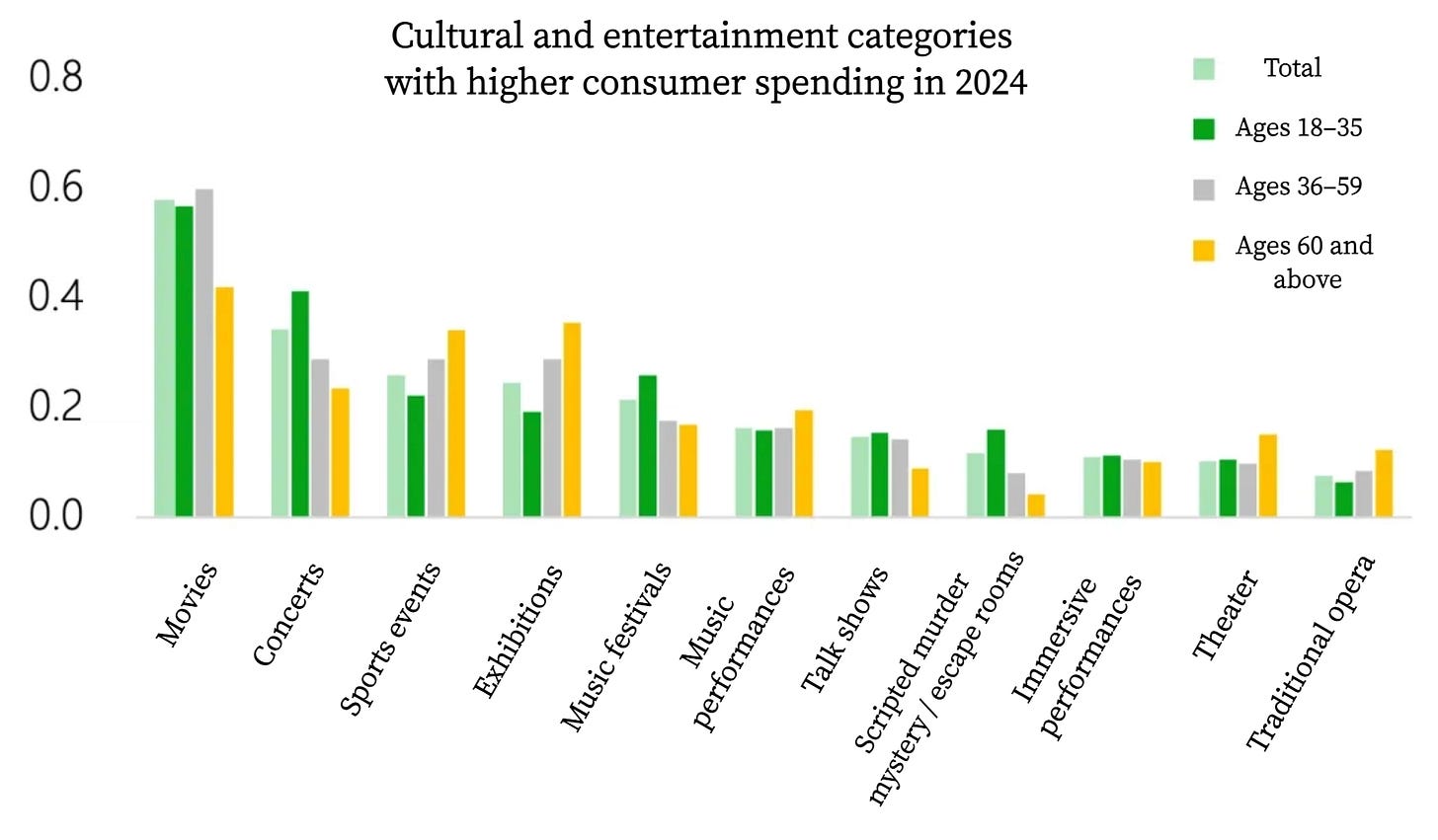

They are the mainstay of cultural and entertainment consumption. Financial and physical stability allows them to travel during leisure time, often preferring short domestic trips, group tours, and cultural tourism. They also form the most active base for senior universities and cultural clubs.

According to the China Association of Senior Universities, the number of such institutions grew at an average annual rate of 4.7% over the past five years. On average, there are about 4.3 senior universities for every 10,000 people aged 65 and above. By April 2023, the total had reached 76,000 nationwide, with more than 20 million enrolled learners. A 2024 survey by the China Media Group found that seniors over 60 were more likely than younger cohorts to attend or watch sports events, exhibitions, concerts, theater, and traditional performances.

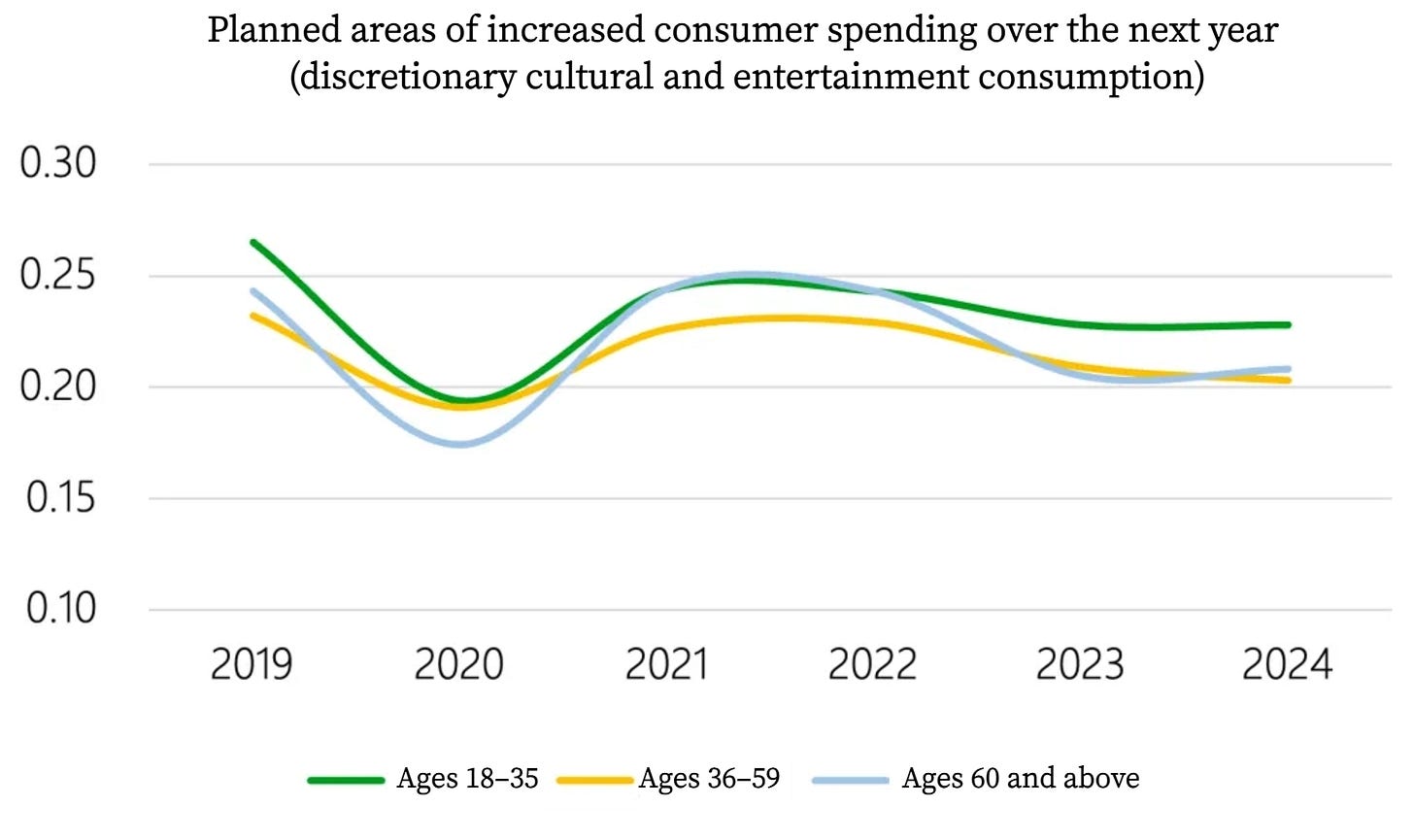

Moreover, while people aged 18–35 remain the dominant force in cultural consumption, the potential of seniors is becoming increasingly evident. In recent years, their spending has nearly matched that of middle-aged groups, and projections suggest that by 2025, seniors will outpace the middle-aged by 0.55 percentage points in participation.

Prudent improvers also invest in home convenience and family comfort, making them potential users of smart home devices, automobiles, and elder-friendly renovations. The senior car market (aged 55 and above) had been quietly building momentum over the past decade: sales climbed from just 550,000 units in 2014 to nearly 1 million in 2017, then accelerated sharply in recent years—reaching 1.5 million in 2022 and 2.27 million in 2023.

A regulatory change in early 2025—removing the age cap of 70 for C1 and C2 driver’s licenses, conditional on passing physical and cognitive tests (commonly known in China as the “three-ability” assessment of memory, judgment, and reaction speed)—is expected to further unlock latent demand. Seniors typically purchase vehicles for medical visits, family transport (especially grandchildren), social gatherings, and road trips, favoring mainstream models with strong comfort and safety features.

Health managers: moderate resources × moderate capability

This segment has decent incomes that cover basic living expenses, along with some room for lifestyle upgrades. Most live with chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, or heart disease. While generally self-sufficient, they require varying degrees of support. Their consumption centers on healthcare products and convenience services.

Their supplement choices are pragmatic and affordable—calcium tablets, vitamins, protein powders. According to national surveys on the living conditions of seniors, 60.6% of elderly supplement users spend less than RMB 1,000 per year. This makes them the backbone of China’s mass-market supplement segment.

As they age, shrinking household sizes, rising rates of solo living, and declining physical ability reduce both the capacity and willingness to cook. The Fifth National Survey on the Living Conditions of Urban and Rural Elderly shows that nearly 60% of seniors live alone or only with a spouse. Cooking, while seemingly routine, involves shopping, storage, preparation, and cleaning—tasks that become burdensome or unsafe for those with limited mobility, weak grip strength, or memory decline. Against this backdrop, food delivery and prepared meals* have become fixtures on senior dining tables.

*Baiguan Note: China’s booming market for prepared meals (ready-to-eat and ready-to-cook)—known domestically as yuzhicai (‘预制菜’)—has quickly become a new staple on senior dining tables.

Data from Meituan shows that elderly users’ daily order volumes have grown steadily, with 2022 orders up more than 30% year-on-year. By 2023, delivery had penetrated more than half of household dining scenarios, and 25% of families reported ordering food for elderly members. Remote ordering by children has become a key entry point for food delivery into senior households.

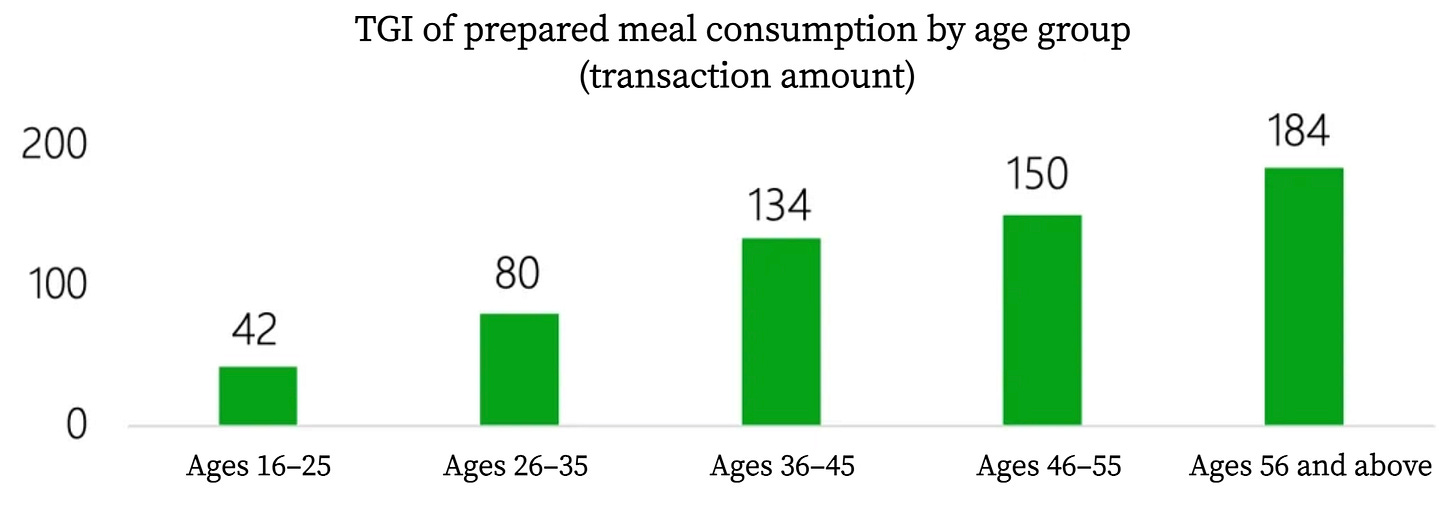

JD.com data reveals a parallel surge in prepared meal consumption. From 2019 to 2021, silver-aged consumers’ purchases grew 190%, with people over 50 accounting for more than half of total sales; 67.9% of this group had consumed prepared meals. Those aged 56 and above showed the highest Target Group Index (TGI), reflecting their strong preference.

Unlike younger consumers, who value convenience and time savings, seniors choose prepared meals for functional and safety reasons. They care about ease of preparation, balanced nutrition, low salt and sugar, and soft textures that are easy to chew. These preferences are shaping new standards for senior-focused food offerings. While food delivery among the elderly remains a “low-penetration, high-growth” market, prepared meals have already become an essential demand on the silver dining table. Importantly, many orders are placed not by seniors themselves but by their children, magnifying growth potential through family purchasing.

These four consumer groups are among the most frequently examined archetypes in market research and together form the core paying segment of China’s elderly population.

The selectively overlooked groups

Senior consumers are not evenly distributed. What the media and markets most often highlight are the “visible samples”: healthy, affluent seniors who are easily reached through commercial channels. But beneath the surface lies a much larger group—constrained by limited income, declining physical function, the digital divide, and weak offline access. Many are effectively excluded from the mainstream consumption market. Basing forecasts solely on visible samples risks systemic bias.

The conservative, pragmatic core of senior spending

In many reports and media narratives, seniors are depicted as embracing new trends and eager to spend: the spotlight often falls on smiling tourists, silver-haired influencers in stylish outfits, and the curated lifestyles of upscale retirement communities. Such portrayals carry strong visual appeal but obscure the underlying consumption attitudes of the majority.

For most seniors, the guiding principle is frugality: “money must be spent where it matters.” Family resources are first directed toward projects deemed vital and long-term—children’s housing, weddings, or cars—seen both as investments in future security and as obligations rooted in traditional family responsibility. Frugality is regarded as a virtue, so spending always requires a clear justification. Tangible goods with lasting value are far more acceptable than abstract or experiential services, with subscription models in particular often dismissed as “non-essential.” Seniors are highly price-sensitive, prioritizing cost-effectiveness over brands or aesthetics.

When lack of consumer literacy leaves seniors vulnerable

This generation lived through China’s abrupt transition from a production-oriented society to a consumer-driven one. Having grown up under scarcity and a planned economy, they later faced a sudden explosion of marketization and commercialization in adulthood. Without systematic guidance—whether from family or school—on new retail channels, advertising formats, rules, and risk awareness, most lack strong consumer judgment. Social isolation and emotional vulnerability further make them particularly susceptible to highly personalized, “caring” marketing.

This dynamic often leaves them swallowing losses in contradictory ways. Some engage in compensatory spending when finances allow, yet remain drawn to bargain hunting. They might skip a RMB 79.9 buffet but stockpile dozens of RMB 9.9 trinkets online. When warned about scams, they retort, “You just don’t understand.” They defend dubious products with, “It has a factory address.” And to children who question their “adopted sons and daughters” from livestreams, they reply, “At least they call me more than you do.” The cautionary phrase they once told their children—“Everything online is a scam”—has boomeranged back to them.

Seniors thus represent both an underserved market and a lucrative yet highly fragmented, information-poor, and emotionally fragile consumer base. Until high-quality elder-focused supply matures, low-cost, easily replicated, high-margin “elder exploitation” businesses will fill the gap. Often, all it takes is a livestreamer repeatedly calling viewers “grandpa” or “grandma” to trigger enthusiastic purchases.

The 80% reality: most seniors spend little

Within the senior consumer base, those with limited resources and capabilities make up a large share. Behind the silver economy narrative lies a stark truth: the majority of seniors remain low spenders, with consumption disproportionately shaped by a small, visible minority. This low-spending pattern is especially evident in seniors’ most closely watched categories—health supplements, travel, and elder care.

Supplements: Over 80% of seniors do not take them. Among those who do, more than 80% spend less than RMB 3,000 annually. Although supplements are often viewed as the quintessential product for older consumers, a survey on the Living Conditions of Urban and Rural Seniors data shows otherwise: only 16.6% of seniors report using supplements. Of these, 60.6% spend less than RMB 1,000 per year, 24.0% spend RMB 1,000–2,999, 6.5% spend RMB 3,000–4,999, and just 8.9% spend over RMB 5,000. A separate nationwide survey (CLHLS 2018) puts actual penetration among adults aged 65 and above even lower, at roughly 12%.

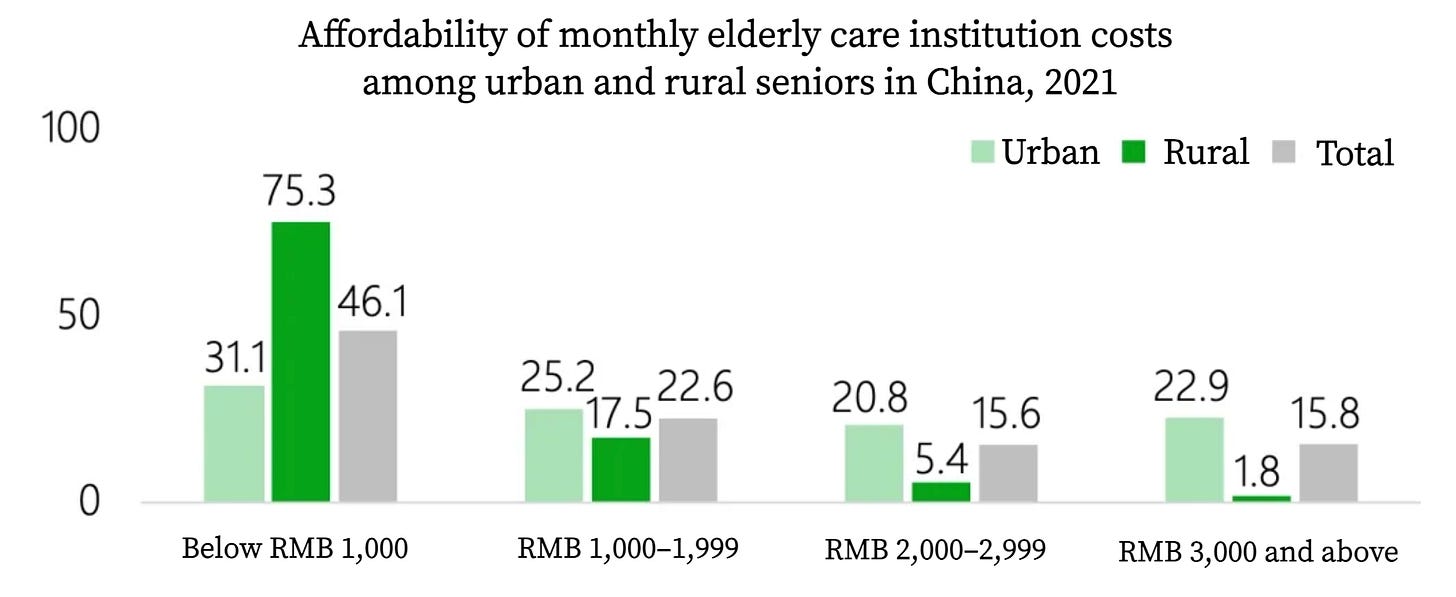

Elder care: More than 80% of seniors cannot afford standard retirement home costs. According to CEIC data, in 36 major cities, the average monthly fee for self-sufficient seniors exceeds RMB 2,600—including accommodation, meals, and basic care—and is even higher for semi-dependent or disabled residents. Survey data show that only 15.8% of seniors can afford RMB 3,000 or more per month, meaning over 80% remain priced out of institutional elder care.

Travel: Over 80% of seniors did not travel in the past year. Among those who did, more than 80% spent less than RMB 5,000 annually. According to the 2021 Survey on the Living Conditions of Urban and Rural Seniors, only 9.1% traveled in 2020, and even with some growth in recent years, the share is still estimated at under 20%. Among the small group who do travel, the majority spend under RMB 5,000 a year—pointing to a market still dominated by short, budget-friendly trips.

The pattern is clear: across key categories—supplements, retirement homes, and tourism—the majority either do not participate at all or remain in the low-spending bracket.

China’s senior economy is not a simple “blue ocean.” It is vast, layered, and riddled with both opportunities and pitfalls. Its essence is “large base × high heterogeneity”: strong overall scale and growth potential, but vast disparities in spending levels. Scalable opportunities will come not from undifferentiated optimism, but from precisely matching subgroups, serviceable scenarios, and sustainable business models.

My take

Why split China’s grey tide into hair-thin groups? Personally, I see three takeaways from this great article.

First, draw the finest slice, not the biggest circle. Before a single yuan is spent, nail down exactly who you’re serving: how many grandmothers and grandfathers within a ten-year birth band, how much they can actually pay, and how often they’ll open their wallets. Over-count the grey tide and you’ll build a palace for a village—then watch inventory rot and margins drown.

Second, once you’re inside the right yard, seniors likely stay. Familiarity beats flashy ads; trust is a lifelong contract. Win them once and they’ll keep the same travel agency, the same pill brand, the same breakfast stall—year after year—turning your customer-acquisition cost into a one-time entry fee.

Third, profits may also come from the quietest voices—but only if you’re willing to do the hard, on-the-ground work. Village grandpas without apps and grandmas without data plans don’t appear on dashboards, but their needs are vast and competition is thin. Reaching them is hard: you must squat on the lane curb, piggy-back existing clinics, and price for a pocket that holds only folded bills. Yet thin-margin, high-frequency sales—subsidised just enough by local government—add up quickly when idle assets are put to work. I searched online and found some uplifting examples:

In Ningxia’s Tongyi village, a derelict fish pond and drying yard were simply re-leased; anglers’ tickets and night-market stall rents now fully finance an 18-bed nursing home that charges residents zero fees.

In Gutian, Fujian, a ¥3 lunch canteen covers its costs with a tiny on-site grocery counter plus monthly on-site pharmacy sales, and the same micro-format has already been copied in 48 neighbouring villages.

In Caoxian, Shandong, 200 shared e-tricycles (¥1 per 3 km) pay themselves off in 18 months through side ads and parcel deliveries, proving that even a village road can become a revenue-producing asset.

Lease the pond, corner the canteen, share the bike—then paste the math across thousands of similar townships and turn yesterday’s waste into today’s steady cash.