The Rise of "Ugly Cute" IPs: Why Young Chinese Have Become Obsessed with "Ugly" Things

In a high-pressure era, imperfect, empathetic items are outpacing luxury

As China enters the Year of the Horse after the upcoming Spring Festival in February, horse and pony plush toys have certainly become sought-after items. However, this year, a “crying pony” plush toy suddenly went viral online.

It began as a simple manufacturing mishap in Yiwu, Zhejiang Province—the world’s small commodities capital. A factory worker accidentally stitched the mouth of a red plush horse upside down, turning its intended cheerful grin into a downturned pout. Originally designed as a lucky mascot bearing the phrase “money comes quickly” (a pun on “horse” sounding like “money” in Chinese), the toy was meant for the 2026 Lunar New Year celebrations.

Factory owner Zhang Huoqing explained in an interview with Xinhua: “It was simply a worker’s mistake—the mouth was sewn upside down.”

But what started as a defective item suddenly went viral after a buyer in Hangzhou posted photos on social media, dubbing it the “Cry-Cry Horse” (哭哭马). Netizens flooded the comments, asking where they could get this defective version. Many netizens added labels like “Monday horse” and “overtime horse” next to the “Cry-Cry Horse,” jokingly referring to their daily grind at work. (”Horse and cattle” is internet slang used by the Chinese to describe employees who face repetitive, grinding work, burnout, and stress.)

Sales skyrocketed from 400 units daily to over 15,000, with the hashtag #YiwuCryCryHorse going viral. The toy’s defiant yet pitiful gaze resonated deeply with young professionals, spawning memes, keychains, and even blockchain tokens.

As a matter of fact, the “Crying Pony” plush isn’t an outlier. As I scroll through social media feeds, I’ve noticed something intriguing unfolding in China’s consumer scene over the past year: young people have suddenly developed a real fondness for “ugly-cute” things. They’re ditching sleek, luxurious aesthetics in favor of items that are quirky, imperfect, and sometimes straight-up ugly.

Another example is the viral story of how a woodcarving grandpa in Beijing suddenly blew up earlier this month.

For over a decade, an elderly man sat by Beijing’s Shichahai Lake, carving and selling wooden sculptures from a simple stall. His works—lopsided animals and figures with exaggerated, rough features—defy traditional standards of beauty. The abstract style often makes it hard to recognize what the figures are supposed to be, revealing that his craftsmanship is far from masterful.

But earlier this month, videos of his creations went viral, drawing crowds of young fans who queue up before he even arrives. He originally came from rural Anhui province and learned carpentry without formal training, relying entirely on self-exploration.

One of his most sought-after pieces is a take on “Lina Bell” (the viral pink fox IP from Disney, hugely popular among Chinese fans in recent years). Yet his version looks nothing like the original. When asked about it, he simply said: “I saw it on a lady’s purse—it looked cute—so I carved it based on my own interpretation.“

Netizens compare his style to Picasso, with comments like “more abstract than Picasso.” Some joke that “even if Disney wanted to sue him, there’s no way to prove IP infringement.”

His woodcarvings became so viral that daigou (proxy shopping) turned into a legitimate side hustle for Beijing locals, as out-of-towners paid premiums just to get one.

But behind the scenes, what truly drives the enthusiasm is the perseverance of “Woodcarving Grandpa,” whose real name is Hu Maoying. Despite his unskilled craftsmanship, Hu’s persistence for more than 10 years has won him attention. Originally from Anhui province, Hu moved to Beijing with his family 20 years ago as a migrant worker. Like many other migrant workers, he took on mundane jobs such as cleaning and part-time work before deciding to sell his woodcarvings.

Hu sourced much of his raw material from the trash—whether it was from manufacturing sites, fruit trees, or even garbage. He struggled for over 10 years before going viral. But what is often seen as “struggling” was, for Hu, simply an enjoyable daily routine. He spent over 10 years at his stall before gaining viral attention. For over ten years, he sold only a minimal amount—sometimes just a few dozen RMB per day—yet he kept going.

Some netizens exclaimed: “Many years ago, I passed by him when I lived in Beijing and bought one. I can’t believe that, after decades, he’s still there and his woodcarvings still haven’t improved.” These comments, though half-jokingly pointing out Woodcarving Grandpa’s lack of skill, convey a subtle sense of nostalgia and hope.

In an interview with Sanlian Life Lab, Hu said: “Making it to Beijing and still supporting myself—that’s already me being excellent.“

The 10 years of perseverance without skill improvement—that blind, almost absurd self-confidence—struck a chord with many young people who are also striving to make a living in big cities.

Some people see echoes of their own mundane yet persistent lives. And some people say, “Seeing these cute and abstract little things, I feel like tomorrow will be a bit more interesting.“ [*]

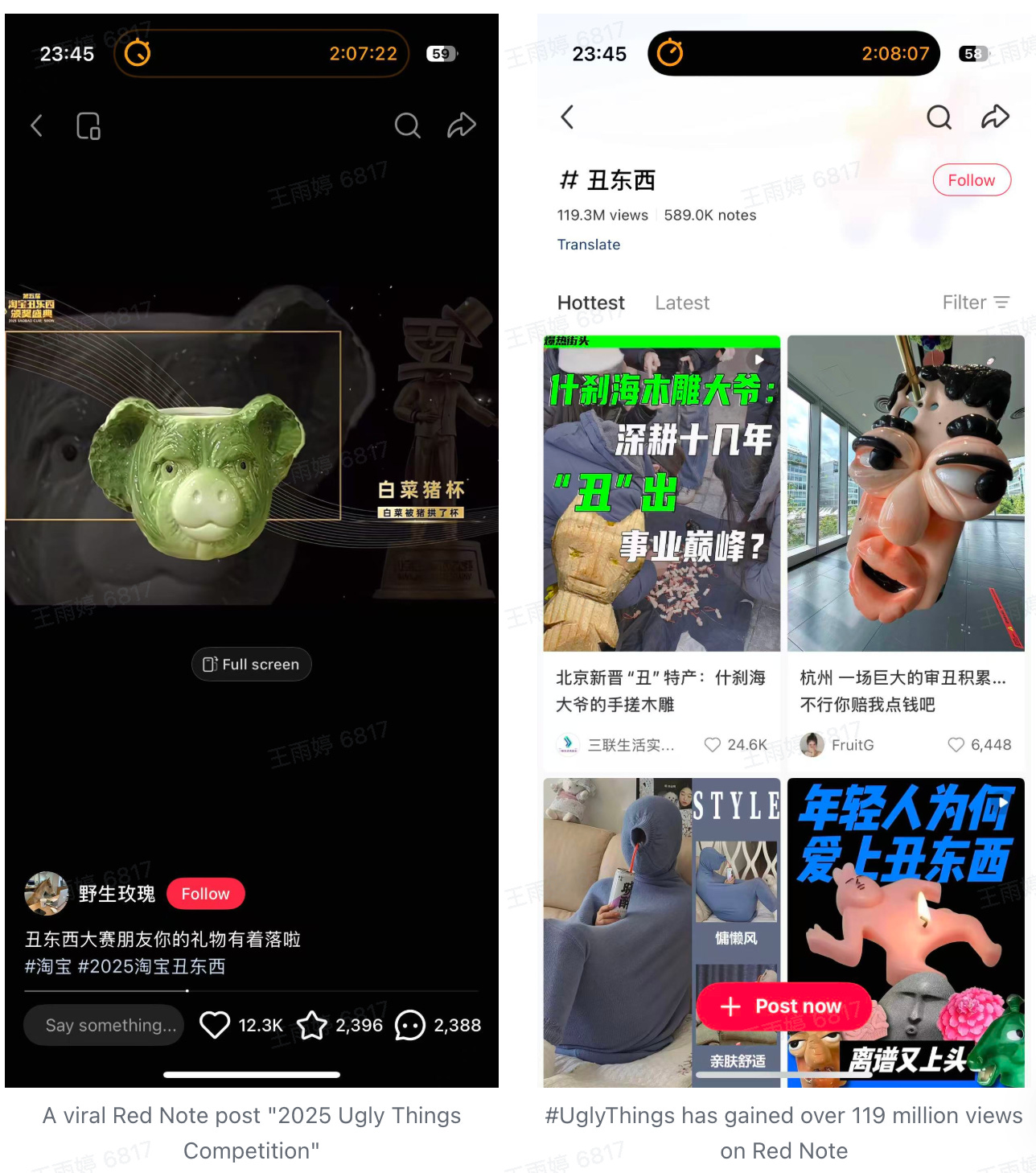

Over the past few years, sharing “ugly but cute” things on Chinese social media like Xiaohongshu has become a trend. Young consumers post photos of the “ugly” yet one-of-a-kind souvenirs and keepsakes they bought serendipitously, often with captions like: “The uglier it is, the cuter it gets—the uglier, the more I want it.“ In contrast, many painstakingly perfected items ironically see poor sales.

If you observe closely, many “national-level” IPs in China are also “ugly but cute.” For instance, one viral figure is Dudu from Nanjing Hongshan Forest Zoo.

Dudu, a male white-faced saki monkey at Nanjing’s Hongshan Forest Zoo, has captivated millions with his striking appearance: dense black fur framing a ghostly white face. His look is far from conventionally “good-looking,” yet he became one of the most beloved superstars.

Spending his days mostly eating and lounging, he’s unflappable—like he’s above it all—in stressful times, which feels deeply relatable. This quirky animal soon turned into a nationwide cultural mascot. Netizens call Dudu “大明星” (the super idol), with some traveling inter-city just to see him. Sometimes, after a long journey and paying for a ticket, visitors would leave without seeing him because Hongshan Zoo was designed in a way that allowed animals to choose not to appear in front of the tourists. However, this didn’t stop visitors from coming back time and time again, just to try to see him.

His popularity also created real business for the zoo, as tourists rush in for merchandise: badges, magnets, and even pancakes shaped like Dudu.

This trend goes beyond just “ugly” appearances. Another correlating trend is that netizens are increasingly embracing things that are absurd by nature. A prime example is the app “死了吗” (Sileme, literally “Are You Dead?”), which recently topped the paid charts in China’s Apple App Store. (The name is a playful pun on the food delivery app Ele.me, which means “Are You Hungry?” in Chinese.)

Created by a developer born in the ‘95s, the app asks users to check in daily to confirm they are still alive by pressing a green button. If you haven’t checked in for a couple of days, it emails your emergency contacts. There’s no login, no personal data collection—just a blunt, existential daily ritual. Despite its simple, absurd, and almost comical functionality, the app became a viral meme across the internet (rumors even say the team attracted investors interested in funding them).

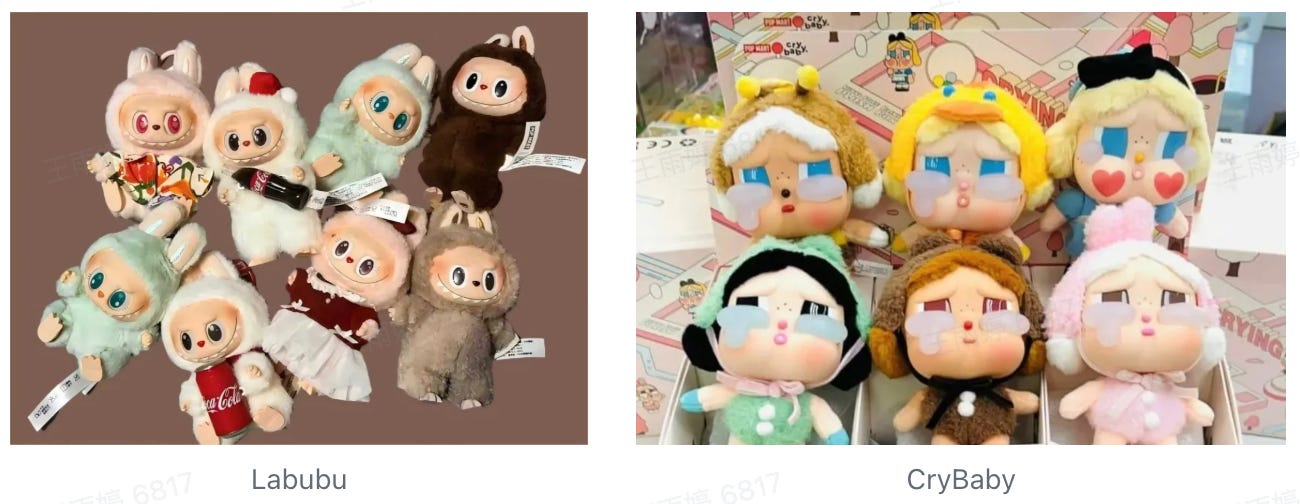

This psychological pivot—rooted in anti-perfectionism and vulnerability—fuels the inevitability of many popular IPs in China. The trend points to bigger opportunities in China’s IP economy—it shows that the success of “kind-hearted but clumsy” personas, such as Labubu (which isn’t pretty by standard judgment) and Pop Mart’s latest IP “CryBaby,” is no coincidence.

Pop Mart branded its latest IP, “Crying Babies,” as an encouragement for emotional expression, challenging societal norms that suppress vulnerability and presenting the CryBaby as an act of bravery rather than weakness.

Young consumers are turning away from the allure of sleek, luxurious, and perfect items. “Ugly but cute” things remind them they can be as quirky and imperfect as they want. In an environment where pursuing an abundant career and life in the city has become increasingly competitive and stressful, embracing “ugly things” sparks empathy, humor, and nostalgia for simpler times.

These “ugly” items also serve as an anchor: despite not being the top student or employee, they still deserve fulfillment just by being ordinary people—doing what they like every day, living simple and sometimes plain days for the next decade. Even then, they deserve self-worth, meaningfulness, and the hope that someday they’ll have their own spotlight moment, just like the woodcarving grandpa.

Thanks for reading through! I’d like to share my own dearest “ugly-cute” thing with you guys :)