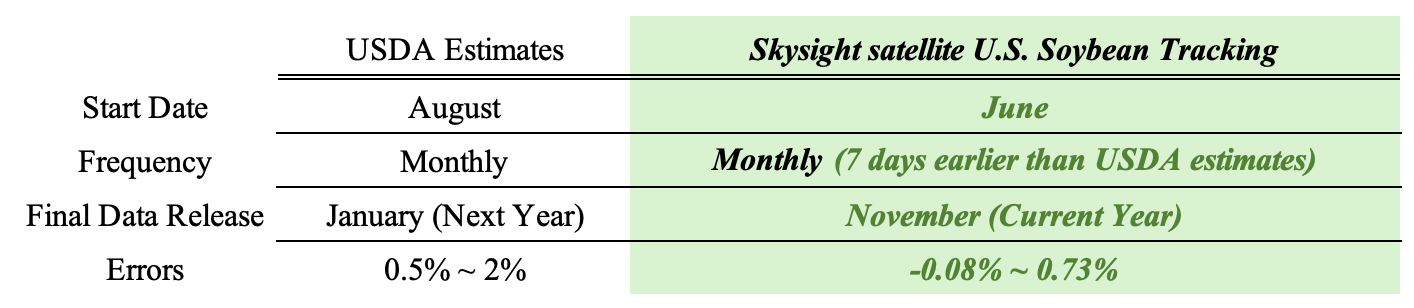

Baiguan is a data-driven newsletter dedicated to scouting and synthesizing diverse data sources to provide deep market insights—this commitment to alternative data is the foundation of our collaboration with Skysight Technology, a leading provider of satellite remote sensing and alternative data services.

Established in 2017, Skysight brings together an elite background in aerospace research, macroeconomics, and financial analysis, providing institutional-grade solutions including standardized financial indices, supply chain insights, sector monitoring, and tailored analytical models across macro trends, commodities, and ESG.

On November 12th, 2025, the U.S. government concluded a record-breaking 43-day shutdown. While the machinery of the state was paralyzed, the global market was obsessing over a singular data vacuum: Was the American soybean harvest a bust, and had Beijing finally blinked?

The 2025 Timeline of the “Soybean Gambit”

Feb - March: A 10% U.S. tariff on China takes effect; China retaliates by weaponizing soybeans.

April - August: A brutal “tug-of-war.” China effectively halts procurement; U.S. exports to China drop to near zero.

August - October: Harvest season. China maintains its “zero-buying” strategy, delivering a massive blow to U.S. farmer confidence.

October 30: The Busan Summit offers a “de-escalation” signal, with soybean purchase commitments as a centerpiece.

December: U.S. officials report that China is actively fulfilling a 12-million-ton commitment, with over 7 million tons already ordered.

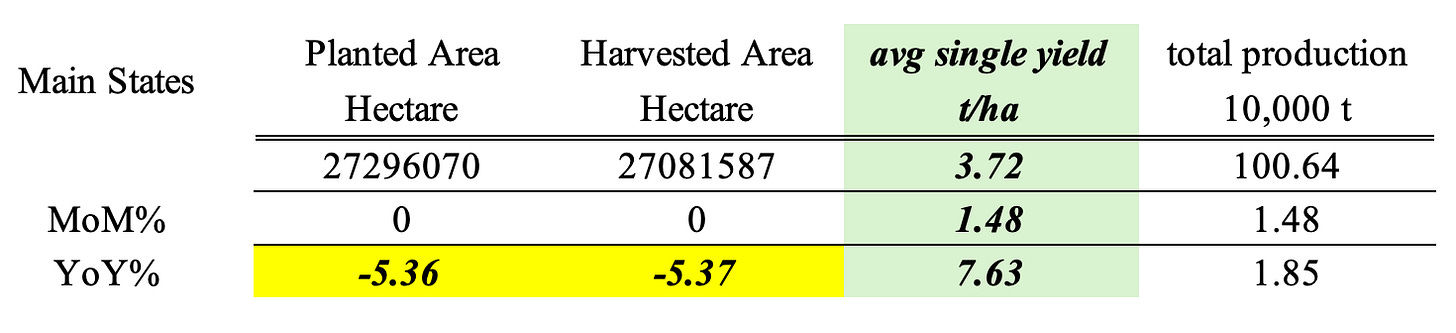

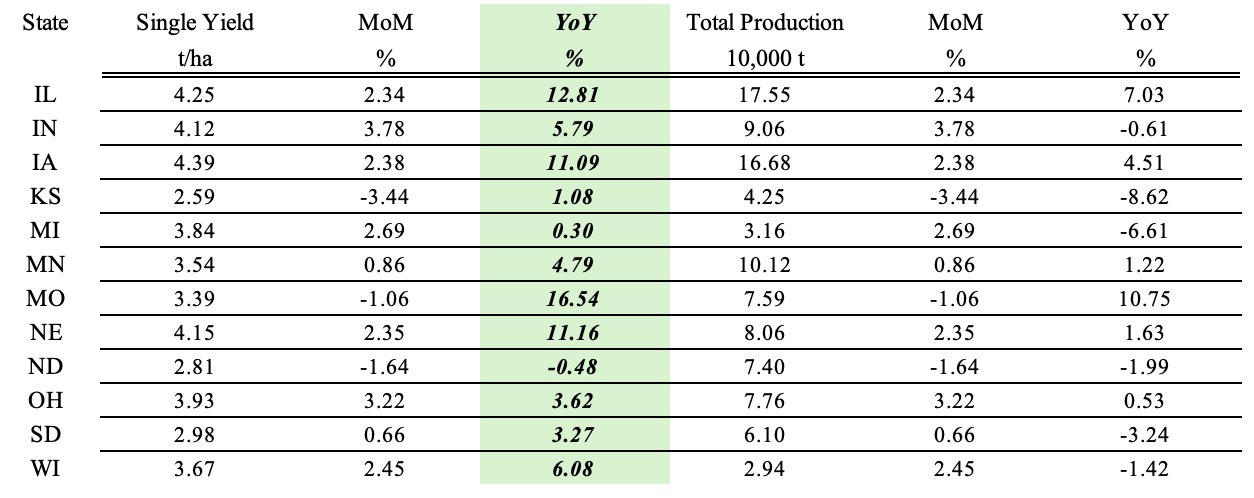

With the USDA officially blind due to the shutdown, satellite remote sensing by Skysight Technology revealed a startling divergence -- while total U.S. soybean plant area is contracting, productivity is surging. Yields in primary producing states hit a projected 3.72 tons per hectare.

In an era where AI, semiconductors, and humanoid robotics dominate the headlines, it seems counterintuitive that a “low-tech” primary agricultural product could remain the most volatile chip on the US-China geopolitical chessboard. The question then is, how much weight does a single grain of soy actually carry?

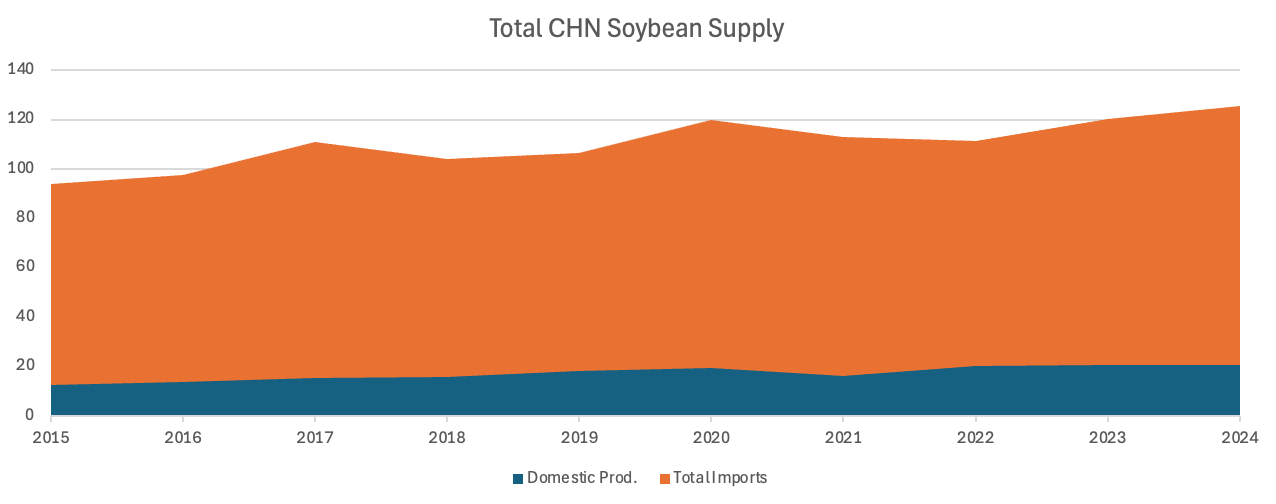

1. China as a Customer

Importing Soybeans = Importing Virtual Lands

The logic of the U.S.-China soybean trade is often reduced to a simple supply-and-demand curve, but viewed through the lens of macro-strategy, it is a resource arbitrage.

The U.S. possesses the world’s most efficient farmland, and China commands the world’s most massive demand for protein. For Beijing, importing soybeans is not a failure of domestic farming, by importing “land and water-intensive” crops, China effectively outsources the environmental and resource costs to foreign soil. This allows it to hold the “18亿亩耕地红线”(120 mn hectare Farmland Redline Policy) and prioritize the absolute self-sufficiency of primary staples like rice and wheat.

Food or Feed Divide

Despite record-breaking domestic harvests in 2024, China’s import dependency remains locked above 80%. This reveals a structural “hard floor” in the market:

Domestic Soybeans: Primarily reserved for human consumption—the edible market for tofu and soy milk.

Imported Soybeans: The industrial backbone used for large-scale crushing and livestock feed that’s largely driven by the rise of the middle class as the Chinese diet shifts toward meat

Unless there is a massive regression in Chinese dietary habits, this “80/20” dependency is a permanent fixture of the geopolitical landscape.

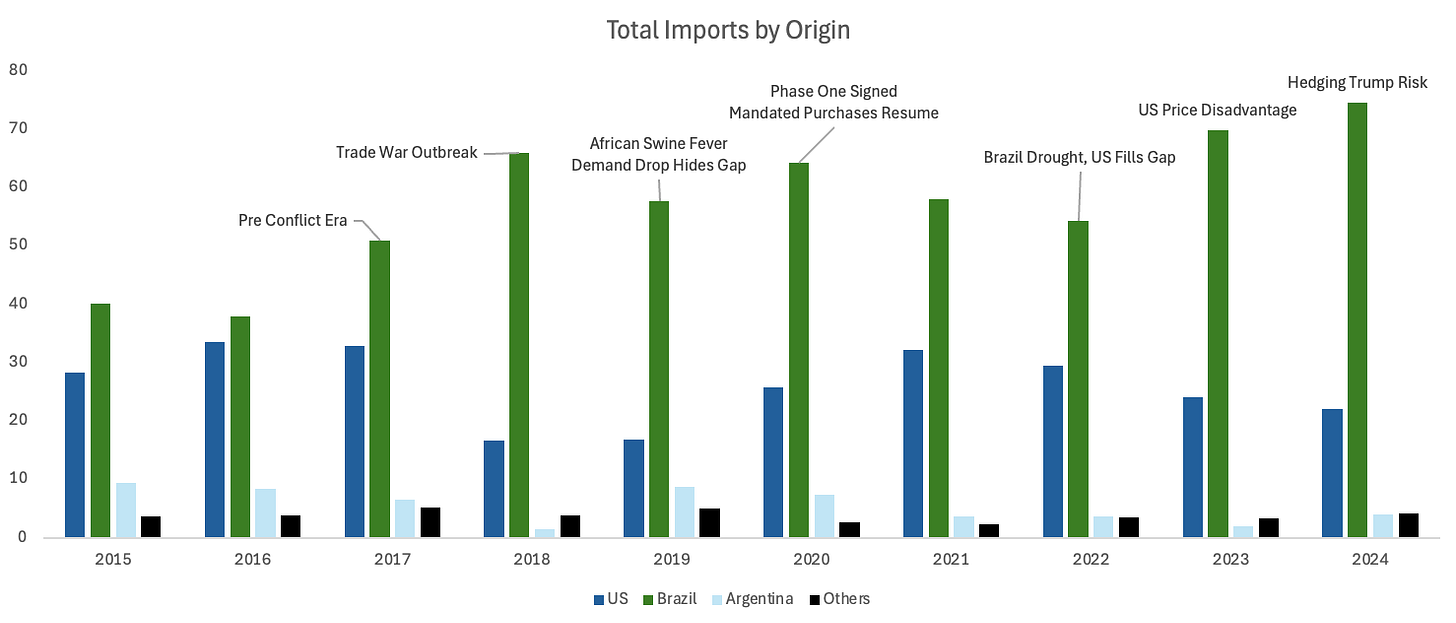

De-risking the “Soybean Circle”

Before 2018, the U.S. was one of the primary providers, commanding 40% of the market. Today, American beans have been relegated to a marginal buffer role. This is a proactive de-risking designed to move the U.S. from a core supplier to a secondary swing producer.

State-owned buyers now prioritize South American crops by default, turning to the U.S. only during the South American off-season or as a diplomatic currency to satisfy specific “de-escalation” agreements.

This transition has paved the way for a new Brazilian hegemon. By 2024, Brazil dominated nearly 70% of the Chinese market, exporting 3.5 times more than the U.S. This dominance was not an accident of nature but the result of a decade-long, aggressive “picks and shovels” strategy orchestrated by China’s state-owned giant, COFCO International.

Through the strategic acquisitions of Nidera and Noble Agri, COFCO secured the critical logistics nodes that bridge the gap between Brazilian farms and Chinese ports. The expansion of the STS11 terminal at the Port of Santos has effectively created a logistical moat. By slashing transport costs and streamlining the supply chain, China has ensured that Brazilian beans remain price-competitive even during the traditional U.S. export window from October to January.

2. U.S. as a Supplier

Why the U.S. Midwest is Nature’s Factory

Viewed through the lens of natural endowment, the American “Corn-Soybean Belt” is an unrivaled agricultural fortress. Sitting on the world’s most fertile soft black soil, U.S. farmers enjoy deep organic layers and high water retention that their counterparts—who must battle acidic soils with massive infusions of lime and fertilizer—simply cannot replicate. This is a “natural cost advantage” that begins beneath the topsoil.

The true industrial cheat code isn’t just the soil; it’s the hydrological geography. The Mississippi River system and its tributaries (the Illinois, Ohio, and Missouri) act as high-velocity arteries pumping commodities from the heartland to the global market.

The Efficiency Gap: A single 15-barge tow moves the equivalent of 1,000 large trucks, with many farms located within a stone’s throw of a river terminal.

The Price Wall: In 2016, this geographic advantage translated to a staggering cost differential: shipping a ton of soybeans from Illinois to Shanghai cost $75, compared to $120 from Brazil’s Mato Grosso. This logistics premium is the primary reason the U.S. remains the world’s “preferred” high-efficiency supplier.

The Heartland’s Fragile Crown

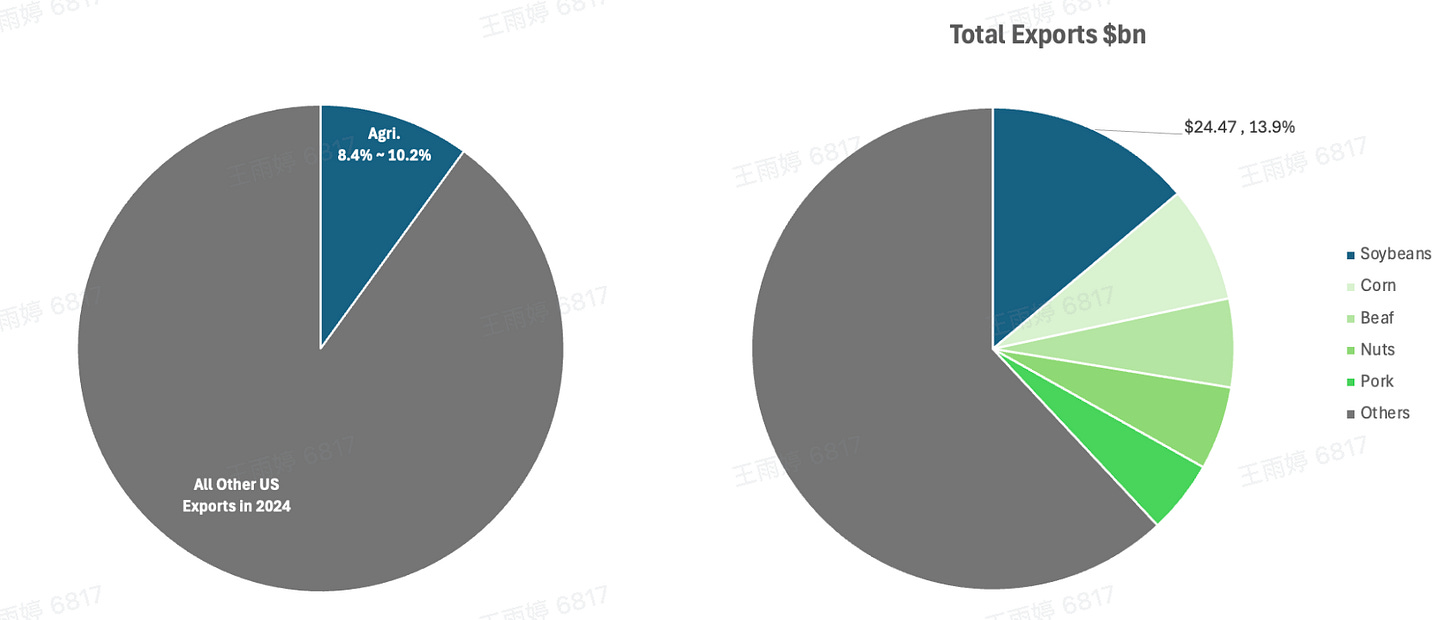

Agriculture is the rare bright spot in the U.S. trade balance—a sector that consistently generates a surplus. At the center of this success are soybeans, the “crown jewel” of American exports.

In 2024, the soybean complex (including meal and oil) accounted for nearly 18% of all U.S. agricultural export revenue.

While this sounds like a triumph, it reveals a dangerous single-crop risk. By specializing so heavily in a crop grown for export, the U.S. agricultural sector has developed a structural fragility. Striking at soybeans is a direct hit on one-fifth of America’s total agricultural export engine. This concentration makes the Heartland uniquely vulnerable to targeted geopolitical tariffs.

A Dependency That Won’t Quit

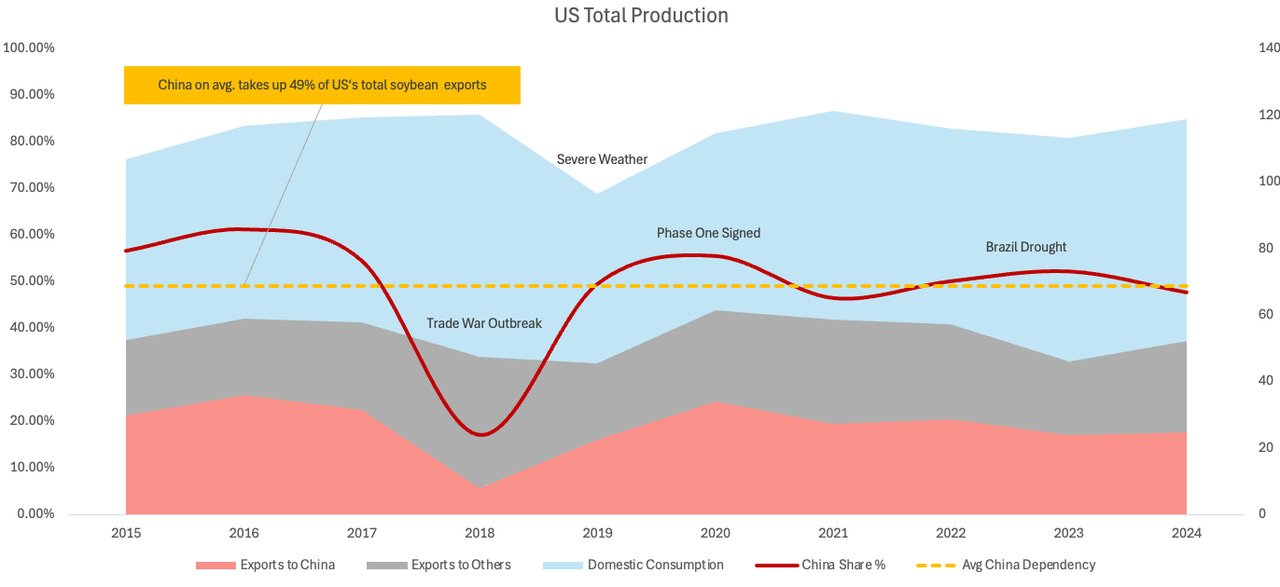

If 2018 was a “black swan” event for trade, it also exposed a painful reality: the U.S. soybean industry is suffering from a “China addiction” it cannot kick.

Before the trade war, the dependency was stable, with over 60% of all exported U.S. soybeans destined for China.

In 2018, that figure cratered to 17.3%, leading to a domestic glut and a total price collapse.

Despite a partial recovery fueled by “de-escalation” agreements, exports have never returned to the 2016 peak of 36 million tons. By 2024, export dependency hovered around 44%, a sign that the industry is still breathing through an oxygen mask.

So, why can’t the U.S. find a new “China”? Washington has attempted to diversify its “protein basket,” but the results have been underwhelming:

The Scale Problem: Combined, the growth in exports to Mexico, the EU, Japan, and Egypt has only recovered 6 to 8 million tons—failing to fill the 11-million-ton crater left by the shrinking Chinese market.

The Crisis Dividend: The 2018 spike in EU imports was a mirage. Europe didn’t suddenly develop a taste for more soy; they simply bought U.S. beans because they were piled high and sold cheap after being blocked from China. This is bargain hunting, not structural demand.

The macro-reality is stark: China still consumes over half of all U.S. soybean exports. If Beijing were to fully sever this artery, the U.S. would face an immediate export loss of over $12 billion.

No other market on Earth—not the EU, not India, not Mexico—possesses the crushing capacity or the livestock scale to absorb what China takes. This is the asymmetric leverage Beijing holds. While the U.S. has the best soil and the best rivers, it is trapped in a buyer’s market where its biggest customer is also its biggest rival.

3. The Great Insulation: Hedging Against Strategic Insecurity

The American Pivot: From “Land Grab” to “Fortress Efficiency”

The U.S. soybean landscape is undergoing a fundamental mutation. This year, the total hectares dropped by 7% —not a coincidence, but a long-term trend accelerated by the 2018 trade war.

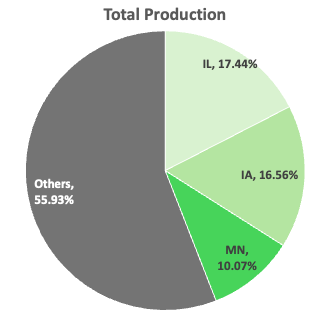

On the ground, regional performance is diverging. The ‘powerhouse’ states, Illinois and Iowa, remain anchored at 17.44% and 16.56% of national output, respectively. Minnesota is seeing robust momentum as yields continue to climb. Kansas, however, has hit a turbulent patch; a yield slump in November dragged total production down by over 8% year-over-year.

Even during the USDA shutdown, eyes above the sky remained sharp. Through continuous tracking, the satellite captured an interesting shift: yield potential is climbing steadily.

U.S. farmers are no longer chasing expansion; they are chasing margins.

The American Heartland is moving toward an intensive production model:

The Yield Explosion: Despite less land, total output remains resilient. Satellite data confirmed that improved climate conditions and high-tech management have pushed yields to a projected 3.72 tons per hectare—a massive jump from last year’s 3.41 tons per hectare.

The Domestic Floor: The U.S. is aggressively building an industrial safety net via the Biodiesel Boom. Domestic crushing is projected to hit a record 68 million tons for the 2025–2026 cycle.

Strategic Infrastructure: A wave of new processing facilities is hitting the soil in North Dakota, Nebraska, and Iowa. By processing beans at home into fuel, the U.S. is reducing its exposure to Chinese “buy-or-die” cycles.

China’s “Strategic Grain Fortress”: The Weapon of Patience

In August 2025, China imported a record 12 million tons of soybeans in a single month without purchasing a single American bean.

If the U.S. is hedging via energy, China is hedging via absolute volume and diversification. This was made possible by a two-pronged strategy of Extreme Tariffs and Aggressive Diversification:

The Tarriff Wall: Under tarriff, American soybeans have effectively been priced out of the Chinese commercial market, allowing Brazil to capture nearly 90% of imports between May and August.

The Argentina Hedge: In 2025, the Argentine government’s removal of grain export taxes significantly boosted its competitiveness. While Argentina’s current exports are a fraction of Brazil’s, its growth trajectory is a key part of China’s dispersed supply roadmap.

The Strategic Stockpile: By the end of 2025, China’s soybean reserves are expected to reach 43.86 million tons—accounting for 36% of total global stocks. This volume has quadrupled since 2015.

By buying heavily when U.S. prices hit a five-year low in late 2024 (anticipating political shifts), Beijing converted high-quality, low-moisture U.S. crops into a strategic reserve. And because China now sits on enough grain to ignore the U.S. market for months at a time, it no longer has to buy out of panic. The U.S. may have the efficiency engine, but China has built a “Grain Fortress” that allows it to dictate the timing of trade de-escalation.

4. Geopolitical Decoding: Why Soybean?

Economic data shows the intensity of a trade war, but only political geography explains why China chose to “strike here.” In 2018, when the U.S. launched its Section 301 investigation, Beijing needed a target that would cause maximum pain in the White House.

The soybean was selected because it possesses the perfect “weapon attributes”:

Massive Volume: It is the single most valuable agricultural product the U.S. sells to China.

Substitutability: Unlike semiconductors, soybeans can be sourced from Brazil or Argentina, providing China with a strategic off-ramp.

Political Sensitivity: The “Soybean Belt” is the heart of Trump’s electoral base.

This asymmetry turned soybeans into the ultimate bargaining chip. By hitting the income of U.S. farmers, China aimed to force agricultural interest groups to pressure the White House into concessions.

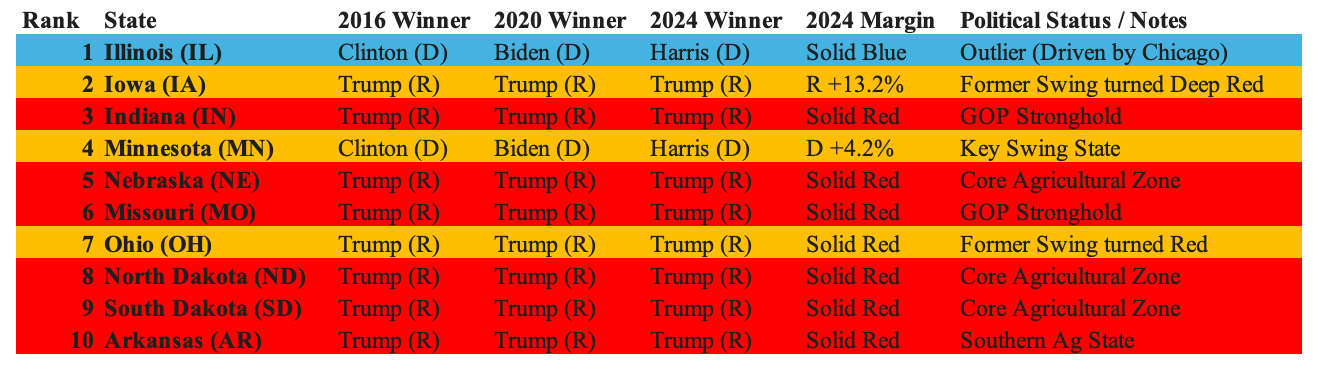

The Electoral Heartlands: A “Red” Infrastructure

Of the top ten soybean-producing states, eight are steadfastly Republican. While states like Illinois and Minnesota often lean Democratic, this is largely driven by urban centers like Chicago and the Twin Cities. Peel back the city layers, and the rural “Soybean Belt” remains a fortress of GOP support.

For the Trump administration, China’s “zero-purchase” strategy was a brutal political stress test. By weaponizing the economic anxiety of the American heartland, China is attempting to force a retreat at the negotiating table by holding the 2026 Midterm elections hostage.

If the GOP loses control of the House or Senate in 2026, Trump’s second-term legislative agenda faces total paralysis. And if China can manufacture enough panic in the “Soybean Belt,” the resulting electoral hemorrhage will force the White House to trade away its “America First” tariffs for farm-belt security.

But, is China’s soybean tactic working?

The soybean weapon may be causing pain, but it isn’t flipping votes.

The Iowa Expansion: In Plymouth County, a titan of soybean production, Trump’s margin of victory actually widened from 9.4% in 2016 to 13.2% in 2024, despite years of bearing the brunt of Chinese retaliation.

The Wisconsin Wall: In Rock and Grant counties—critical bellwethers in the swing state of Wisconsin—GOP support did not collapse under the weight of the trade war.

On the surface, the conclusion seems obvious: now that Trump has successfully secured a second term and the farming states remain “deep red,” then China’s “soybean revenge” has fundamentally failed.

But is that the whole story?

Did the soybean strategy fail?

“Failure” is the wrong framing.

This is not a win-loss binary; it is a high-stakes endurance test where both superpowers are locked in a short-term game of brinkmanship and a long-term state of Strategic Stalemate.

First, the hard fundamentals of global supply dictate that a total severance is mathematically impossible.

On the U.S. side, the stability was not a result of market resilience, but of a massive Fiscal Shield.

The Subsidy Injection: The White House successfully blunted the trade war’s trauma by injecting tens of billions of dollars into the rural economy via “Market Facilitation Programs”. These were effectively “fiscal painkillers” that masked the true wound caused by the loss of the Chinese market.

The Sustainability Trap: This is a hollow victory. The U.S. cannot indefinitely sustain a multi-billion-dollar “governance tax” to keep its farming base afloat. With a ballooning deficit and inflationary pressures, this fiscal safety net is fundamentally unsustainable.

No Alternative to Scale: Even with the “Biodiesel Boom” absorbing more domestic supply, the U.S. has no external market capable of digesting its massive surplus. Abandoning China would mean a painful structural contraction of the entire U.S. agricultural engine.

On the Chinese Side, the structural pivot has introduced its own set of geopolitical and environmental vulnerabilities.

The Two-Stroke Engine: Brazil harvests from February to May, and the U.S. harvests from September to November. This seasonal alternation is the world’s only true guarantee of year-round protein security.

The Brazilian Exposure: By tethering itself almost exclusively to Brazil, Beijing has traded “U.S. Political Risk” for “South American Climate Risk”. Any major drought or political upheaval in Brazil now poses an existential threat to China’s livestock industry, as there are no other suppliers with the requisite scale to fill a Brazilian-sized gap.

Second, and perhaps most crucially, the essence of deterrence here is the systematic escalation of the “governance tax.”

Beijing’s soybean strategy was never a simplistic attempt to flip the ideological switch of the American farmer. In the rural heartland, cultural identity and patriotic narratives frequently override pure economic rationality; a trade war rarely turns a “Red” county “Blue” simply through market pain.

If the soybean weapon didn’t change the ideology of the American farmer, what did it achieve?

To raise the “Cost of Governance” for the opponent.

China’s strategy was never about winning hearts and minds. Instead, the strategy is designed to force the opponent into a state of fiscal and political exhaustion. By making the trade war as expensive as possible for the White House to manage, Beijing turned a “low-tech” commodity into a permanent drag on the U.S. Treasury.

Entering the Era of High-Friction Coexistence

For all the ideological noise suggesting a total decoupling, the recurring tariff salvos and purchase freezes of the 2018–2025 cycle were never truly intended to kill trade. Instead, they represent a paradigm of leveraged interdependence.

Both superpowers are now weaponizing election cycles and short-term policy tools—tariffs, subsidies, and tactical pauses—to extract maximum gain while hedging against the risks of mutual uncertainty.

The soybean has ultimately become the defining microcosm of this High-Friction Coexistence. We must accept that while trade volumes may never return to their 2017 peak, the “Free Trade” honeymoon of decades ago has officially ended.

Yet, the two economies remain more deeply fused than the decoupling narrative suggests. While both nations are aggressively building domestic “fortresses”, they remain tethered by the objective gravity of supply and demand. Beijing cannot forever sever its ties to American protein, and Washington cannot survive the loss of its most significant agricultural customer.

Both sides are desperately seeking “security” through localization, yet they are forced to maintain a minimum viable connection to keep their respective economies functioning.

This state of constant collision and collision-management is not a temporary crisis but the new structural reality. In the coming years, the relationship will be defined by this permanent tension—an era where friction is the constant, but the inescapable pull of mutual dependence continues to foster new, albeit difficult, opportunities.