What's it like to live in a Chinese city fueled by coal?

A trip to Yulin, Shaanxi: wealth, tranquility, and vibrant culture

This past national holiday, I took a slow-speed train from Shanghai to Hohhot. The more than 20-hour-long journey left me exhausted, so I got off along the way and ended up serendipitously in Yulin City, Shaanxi. Located in the northernmost part of the province, at the intersection of five provinces—Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi—Yulin sits where the Loess Plateau meets the Mu Us Desert. Yet, the city’s atmosphere, culture, and the daily lives of its residents took me by surprise.

The most immediate impression came when I took a taxi. The driver’s attitude was remarkably pleasant. In a 2023 article, I wrote about the struggles of ride-hailing drivers—oversupply, the overwhelming power of platforms, and rental companies squeezing their earnings. In Shanghai, taxi drivers often seem irritable and quick to complain. At Hongqiao Airport, if your trip is a short one, drivers can get visibly upset after waiting in line for hours for a passenger. But the drivers in Yulin appeared far more relaxed, unhurried, and content, even with fares as low as ¥5–10. The contrast with Shanghai was striking.

I’ve heard that many locals received substantial cash compensation from the government for land acquisition. They don’t necessarily need the money, but they drive to maintain a daily routine—to have somewhere to be, something to do.

Yulin’s economic profile: An energy hub with pioneering social policies

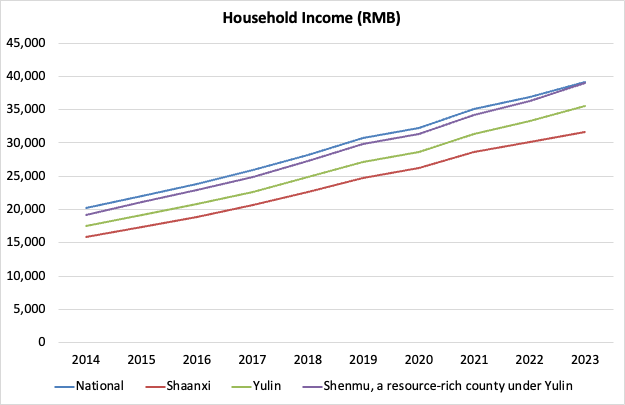

Yulin’s GDP has consistently ranked second in Shaanxi Province, second only to the provincial capital Xi’an. Its economic output even surpasses that of some provincial capitals in western China, making it a crucial economic driver for Shaanxi. With its high-value energy industry and relatively small population (around 3.6 million), Yulin’s GDP per capita is among the highest in Shaanxi and nationwide, even exceeding that of some eastern coastal cities.

Boasting world-class energy and mineral resources, Yulin is often called the “Kuwait of China.” Coal is the absolute backbone of its economy—the Yulin Coalfield is one of the world’s seven largest, with massive reserves of high-quality coal (low ash, low sulfur, low phosphorus, high calorific value). The city is a core base for China’s “West-to-East Coal Transmission” strategy. It also forms a key part of the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia oil and gas field, with abundant reserves of petroleum and natural gas.

Supported by its resource-driven fiscal capacity, Yulin and its affluent counties—such as Shenmu and Fugu—have rolled out social policies that exceed national standards and gained nationwide recognition:

“Shenmu Healthcare Reform” (*): As early as 2009, Shenmu pioneered a “universal free medical care” system. Funded by local fiscal revenue, the policy covers the majority of hospitalization expenses for urban and rural residents at designated hospitals within the city. Although implemented at the municipal level, it demonstrates how resource wealth can support high-level welfare programs.

15 Years of Tuition-Free Education: Yulin has implemented 15 years of free education from kindergarten through high school across the entire city—6 years longer than the national 9-year compulsory education requirement—significantly reducing the financial burden on families.

*National Basic Insurance: Across China, the basic medical insurance system consists primarily of two schemes: one for urban employees and another for urban and rural residents. These schemes provide a fundamental level of coverage, but patients still bear a significant portion of costs through deductibles, co-payments, and expenses for drugs or services outside the reimbursement list. The out-of-pocket burden can be substantial, especially for major illnesses.

Urban infrastructure: A train station with crystal-clear screens and only public service ads

The quality of Yulin’s urban infrastructure is immediately apparent in public facilities like its train station. Unlike the often crowded and commercially saturated stations in major hubs, Yulin Station feels spacious, well-maintained, and thoughtfully designed.

A striking detail captures this perfectly: the digital display screens within the station are exceptionally high-definition, arguably sharper than many home televisions. More notably, these screens are dedicated solely to broadcasting public service announcements (PSAs), with no commercial advertisements in sight.

Well-preserved folk culture in Yulin: prosperity makes courtesy/”仓廪实而知礼节”

If you have visited various “ancient towns” and “old streets” across China, you may have noticed that most of them feel strikingly similar. The reason lies in the fact that many of these historic streets and towns have been restored or reconstructed essentially as commercial real estate projects. To recoup investments quickly, minimize risks, and ensure profitability, developers tend to adopt the most proven and low-risk development templates—standardized architectural designs that can be rapidly replicated nationwide.

Furthermore, shops in these ancient towns are mostly operated by individual tenants whose product selection follows a simple logic: whatever sells well gets stocked. Sourcing from national wholesale markets like Yiwu offers low costs and variety, but inevitably leads to the same products being sold everywhere. Embroidered bags, wooden combs, ethnic-style scarves, and low-quality crafts become the standard fare. Similarly, snacks like stinky tofu, grilled sausages, bubble tea, and skewers—easy to make, widely popular, and highly profitable—naturally become merchants’ first choice, crowding out traditional local snacks that require complex techniques, carry unique regional characteristics, and may appeal to a smaller audience.

However, Yulin Old Street is distinctly different.

Firstly, alongside tourists, the street is also frequented by locals who visit its grocery stores, dairy shops, and food suppliers. Secondly, folk culture is visibly alive and present everywhere. For instance, there is a shadow puppet (”皮影戏”) museum housing the private collection of a German enthusiast. After the puppets were damaged in the floods in Germany a few years ago and the collector unfortunately passed away, the museum has been meticulously restoring them.

To escape the rain, we stepped into a Northern Shaanxi storytelling hall (”陕北说书馆”), where entry was free. We watched a documentary about the art of storytelling and a live performance.

*The game Black Myth: Wukong masterfully incorporates the gritty, narrative strains of Northern Shaanxi Storytelling as a diegetic narrator (Let me show you a glimpse of it with this video clip)

Another example is Colored Cotton Collage Art. As the name suggests, it is a form of relief art created using colored cotton as the raw material, through techniques such as layering, attaching, and sculpting. It is not a centuries-old craft, but rather a unique folk art invented by Mr. Zhang Shiyu, a folk artist from Yulin, in the 1990s. It has been included in the Shaanxi Provincial Intangible Cultural Heritage protection list.

When we went into a small shop displaying colorful cotton collage art, an elderly gentleman welcomed us and explained that the craft wasn’t centuries old—it was actually invented by his father, and now he and his son are carrying it forward. Here, cultural heritage is not a static relic; it is vividly alive and actively present.

As I write this, my initial point was to illustrate the vastness of China and the tremendous disparities that exist between different regions—economically, fiscally, socially, culturally, and in the daily lives of their residents. While young people struggle to find jobs in first-tier cities and the middle class grapples with falling property prices and mortgage stress, there are places where people lead prosperous and tranquil lives.

However, upon closer examination of Yulin’s economic situation, I’ve come to recognize underlying risks. The main concerns are: 1) its heavy dependence on resource prices, and 2) the significant disparities within Yulin itself, between its different areas.

Underlying risks: Over-reliance on the energy sector and uneven development

Yulin’s economic vitality is measured by the rhythm of a single heartbeat: the price of coal. This energy-rich region lives and breathes by the fluctuations of its primary resource—where fiscal health and personal prosperity rise and fall with the market’s every tremor.

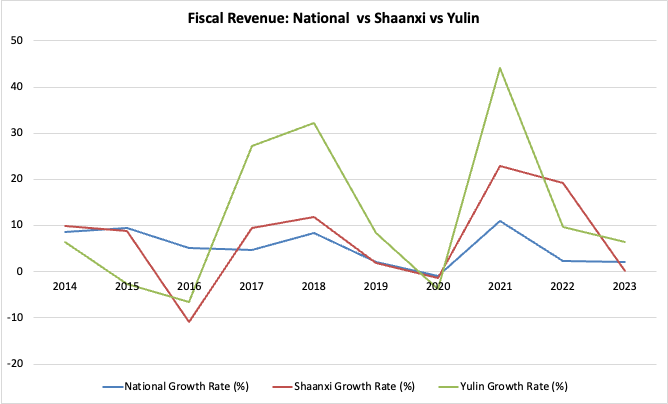

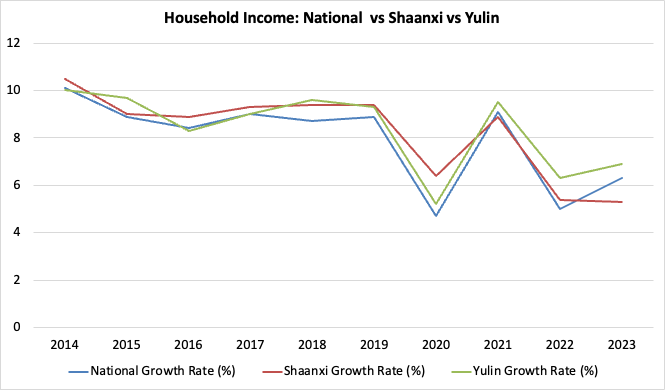

Yulin’s economic trajectory has been closely tied to fluctuations in coal prices. In 2021, as prices surged to historic highs, the city’s GDP and local fiscal revenue grew markedly—with fiscal revenue jumping 44.6% year-on-year—while household incomes also rose rapidly. In 2022, although coal prices retreated from their peak, they remained elevated, allowing fiscal and income growth to continue, albeit at a more moderate pace. By 2023, as coal prices settled into a more rational range, growth in GDP and fiscal revenue slowed further.

Yulin also faces pronounced internal imbalances. At the regional level, resource-rich northern counties such as Shenmu and Fugu—which contribute the bulk of municipal fiscal revenue—enjoy significantly higher per capita incomes than agricultural southern counties. At the sectoral level, industries like energy extraction and chemicals generate far higher incomes than agriculture or traditional services, creating a stark “energy-rich, rest-poor” divide. This dual disparity, both geographic and industrial, highlights the typical “internal inequality” of a resource-dependent economy.