Where does China rank in global arms exports?

China’s modern military capabilities, scale, and global influence

China’s military parade on Sept. 3, held to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War and WWII, showcased a striking display of the country’s evolving defense capabilities. The wide array of advanced weaponry alone was already impressive. The parade made it clear that China is now able to manufacture a more innovative and diverse set of weapons at scale compared to 10 years ago. For instance, the Dongfeng-5C intercontinental ballistic missile can be launched from northern China to strike the U.S. mainland, while the Dongfeng-26D, nicknamed the “Guam Killer,” can target major U.S. military bases in Guam [BBC].

China has also made functional advances in technologies such as drones, extra-large unmanned underwater vehicles, and other unmanned aerial systems. Unlike a decade ago, the parade demonstrated China’s growing ability to organize coordinated military operations, integrating multiple units to act coherently.

Because China has enjoyed decades of peace since WWII, most of its weaponry has not been battle-tested, making it difficult to fully assess their performance for potential global buyers. That said, Chinese military technology is gaining increasing attention internationally. For example, Pakistan’s use of Chinese-supplied Chengdu J-10C fighter jets, reportedly shooting down multiple french-made aircraft in a conflict with India in May this year, marked one of the first significant combat tests for Chinese-made equipment against Western systems.

While rising geopolitical tensions cannot be ignored and conflict is not desirable, it is now worthwhile to set aside political debates and “China threat” narratives to objectively examine the current state of China’s defense capabilities and its position in the global arms trade.

In today’s newsletter, we translate a highly informative overview addressing exactly this question: where does China rank in global arms exports? The original content comes from a YouTube video essay by 巫师财经, whose career began as a banking analyst at China International Capital Corporation (CICC) before co-founding his own fund, and who now produces finance and business content. (For fluent Chinese speakers, the original video essay can be viewed on YouTube here.)

Below is our translation of the video transcript. Some narration scripts and charts have been abbreviated or reformatted for clarity.

Military trade behind the parade: where does China rank in global arms exports?

How competitive are Chinese weapons?

How well do Chinese weapons sell globally? How much revenue do they generate? And who are the buyers?

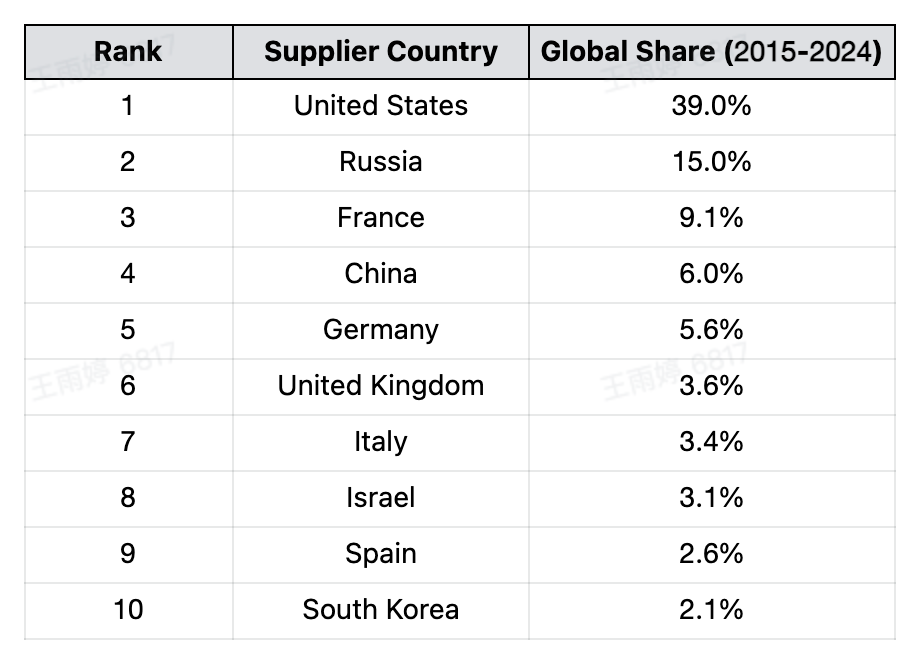

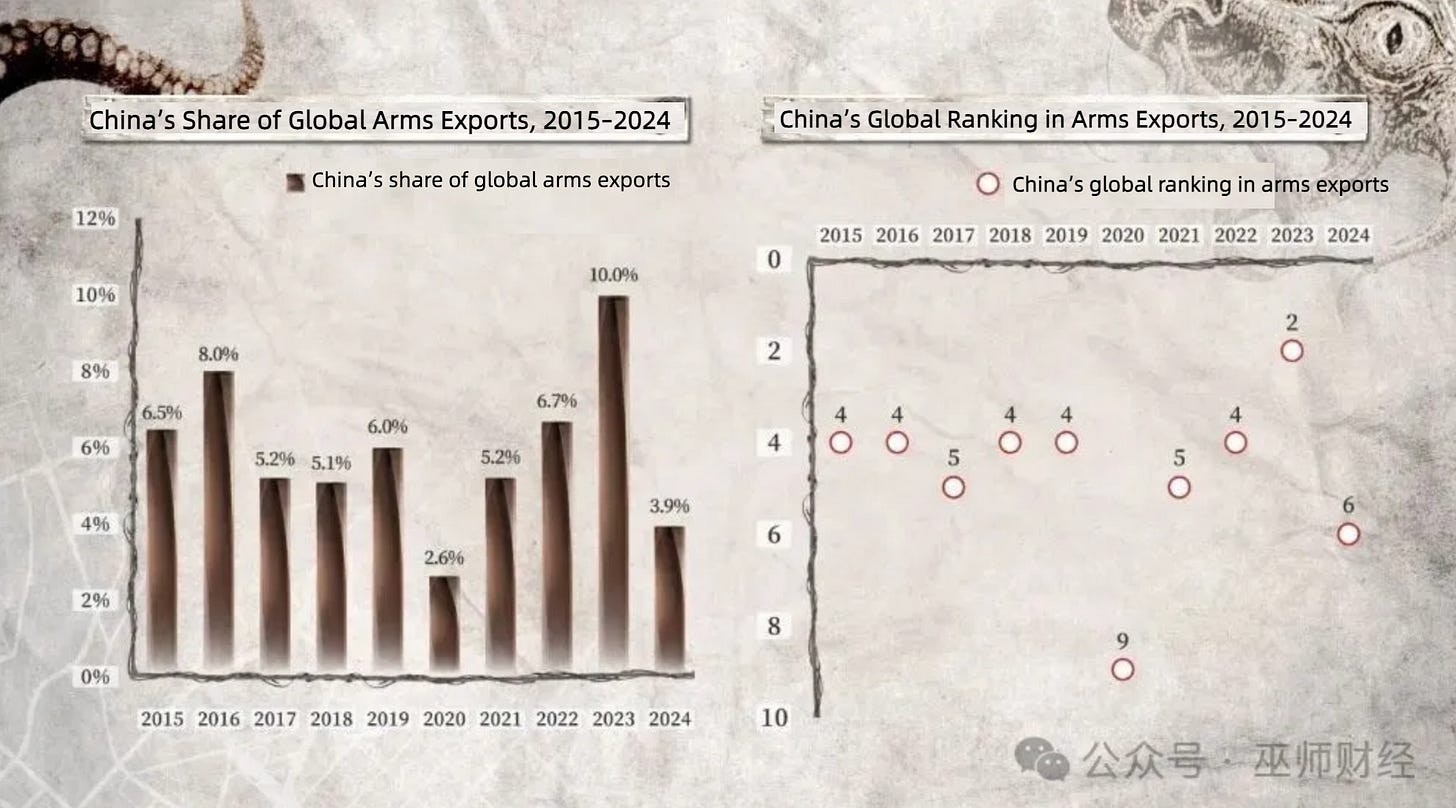

Over the past decade, China accounted for about 6% of global arms exports, ranking fourth. The United States, with roughly 40%, remains the undisputed global powerhouse of weapons exports. Russia ranks second at 15%, though that largely reflects legacy sales.

Viewed in isolation, the trends are striking. Russia’s share, once 21% in 2015, has collapsed in recent years, leaving it on par with China. The U.S., by contrast, has seen a steady climb, reaching 47% of the global market in 2024—nearly half of the world’s arms trade. China, meanwhile, quietly gained ground: between 2021 and 2023 its exports exceeded Russia’s, peaking at 10% in 2023.

In absolute terms, China’s 10% that year placed it second globally.

The turning point came around 2012–2014, when China shifted from being a major importer to a net exporter.

Imports, in fact, have collapsed. China’s share of global imports fell from 7.4% to just 0.2% last year, dropping its ranking from the global top 10 to around 50th.

What lies behind the business numbers? It’s strength.

China’s place in global military power rankings

GlobalFirepower’s 2024 index, covering 145 countries, places the U.S. first, Russia second, and China third. India, South Korea, the U.K., France, and Japan occupy the next five slots.

The ranking, known as “PwrIndx,” aggregates more than 60 factors—from manpower and equipment to resources, fiscal capacity, and geography. A lower score signals greater strength. By this measure, China and Russia are tied at 0.0788. But as with all indices, methodology is political. Western institutions carry their own biases. If the U.S. Navy were publishing the report, China might be portrayed as poised to strike America’s shores—an argument designed to justify bigger budgets. GlobalFirepower, if anything, tilts the other way.

Even so, the pattern aligns with export data: the U.S. dominates in a league of its own; China and Russia make up the second tier; the rest trail far behind. India, though ranked fourth, lags significantly behind the top three.

If you look into China’s specific score composition, the ones holding things back are mostly related to energy consumption, debt issues, and long borders with other countries. When it comes to actual equipment numbers and quality, the scores are very high. Essentially, it all comes down to how the weights are assigned.

But maybe it’s just that after years of doing the dirty work in investment banking, I tend to assume others are always thinking a bit schemingly. At CICC, we used “Dealogic” to cut the data until we ranked first. If total IPOs didn’t put us on top, we narrowed it to state-owned IPOs, or to overseas SOE deals. If that still didn’t work, we built a weighted scoring system that gave larger transactions higher multipliers. In the end, the numbers delivered the headline we wanted: CICC was No. 1. Clients never cared about the methodology—only the headline result. By the same token, military indices should be treated as indicators of trends, not absolute truths. As Nietzsche put it, “There are no facts, only interpretations.”

Does this mean China’s ranking is artificially deflated? In practice, its defense industry has already advanced considerably. Arms import data tell the story: between 2020 and 2024, the world’s top arms importers were Ukraine (8.8%, it’s at war, after all), followed by India (8.3%), Qatar (6.8%), and Saudi Arabia (6.8%). Their primary suppliers were the U.S., Germany, and Poland.

Among the top 20 arms importers, almost all sourced from the U.S. and Europe, with only occasional purchases from Russia. Pakistan was the lone exception: 81% of its weapons came from China. This shows that Chinese equipment has yet to gain broad global recognition, or that the current global landscape limits the reach of China’s defense exports. After all, arms trade carries strong political significance, and the diplomatic environment remains relatively challenging.

For now, China cannot break into Western markets. Beyond Pakistan, the question remains: where else can Chinese arms find buyers?

Who is buying China’s weapons?

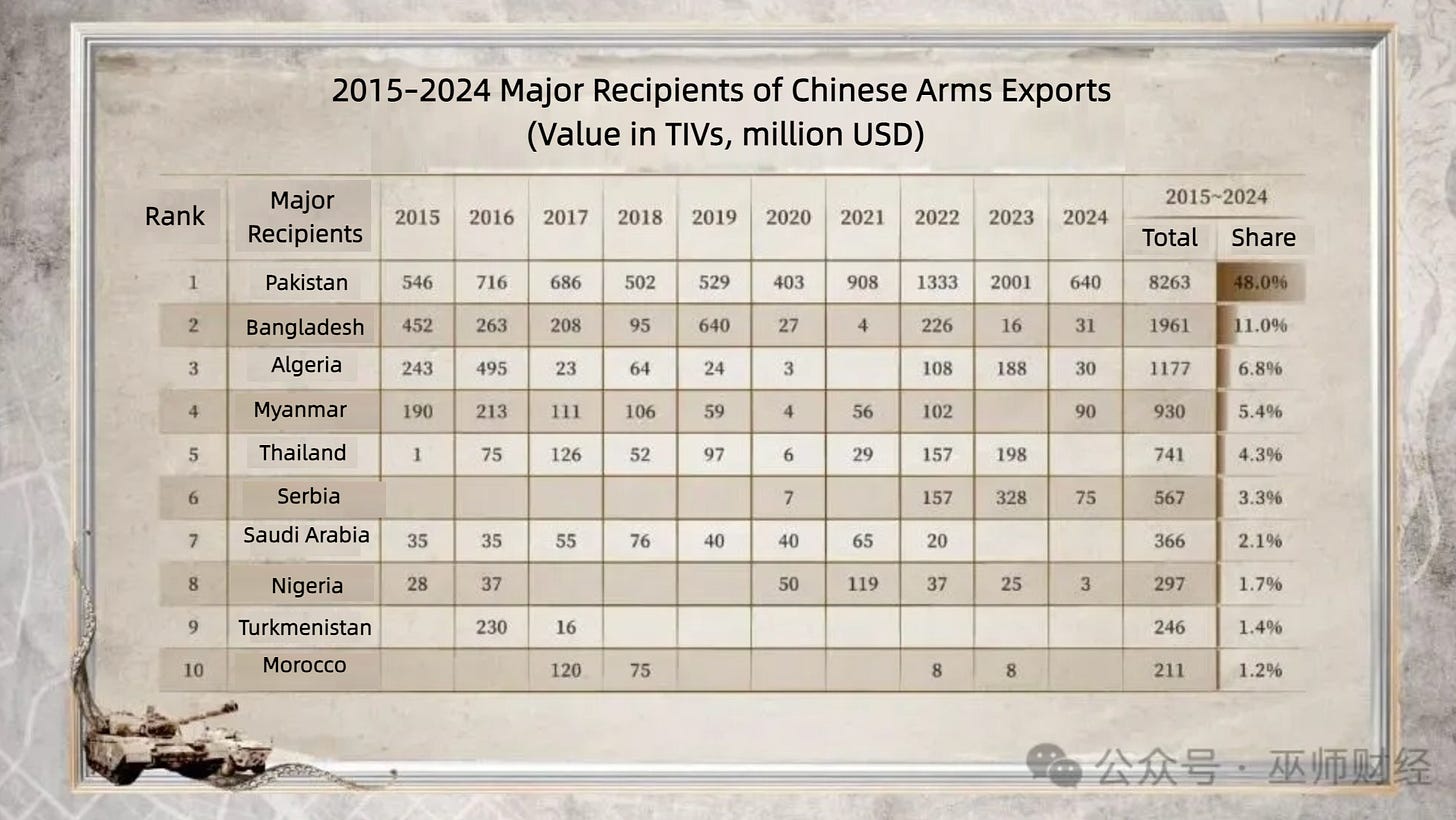

Looking at China’s top ten buyers over the past ten years, these are the countries that have genuinely put down their money. Some might say, ‘Except for Saudi Arabia, aren’t these all relatively poor countries?’ Even so, this is already a solid achievement, achieved through China leveraging two major factors: ‘defense balancing’ and ‘opportunistic openings.’ And that’s on top of the fact that our equipment offers higher cost-performance, comes without political strings attached, and often includes favorable financing—later you’ll see why this matters.

Over a ten-year period—not just five-year—Pakistan accounts for half, ranking first. Bangladesh is second at 11%, Thailand fifth at 4%, and Serbia sixth at 3%, all showing signs of seeking defense balance. Beyond surface-level friendship, this is a key factor allowing us to expand into these markets. The other factor, of course, is taking advantage of ‘opportunistic openings’ (Baiguan: Beijing’s readiness to fill supply gaps when traditional suppliers falter.)

Thailand is a case in point. Beyond its traditionally friendly ties with China, it had already purchased a range of Chinese equipment. But Thailand also sourced heavily from Ukraine, especially tanks and armored vehicles. When the Russia-Ukraine war broke out, China stepped in to fill the gap, and exports to Thailand increased further. According to The Diplomat, between 2016 and 2022 Thailand imported $394 million worth of Chinese arms—well above the $207 million it purchased from the U.S. during the same period.

Myanmar, which accounted for around 5% of China’s exports over the past decade, has become the fourth-largest customer. Once subject to a Western arms embargo, Myanmar began expanding foreign procurement after sanctions eased in 2010. China seized the opening, offering comprehensive arms sales to meet its growing defense needs.

Further up the list, Algeria stands out as China’s third-largest customer—and a reminder that Africa has become a critical battleground in the global arms trade. Between 2020 and 2024, Russia supplied about 21% of Africa’s weapons imports, China 18%, and the U.S. 16%. Algeria is the continent’s heavyweight buyer, at one point accounting for more than one-third of Africa’s total arms imports. Historically, over 60% of Algeria’s purchases came from Russia. But as the war in Ukraine consumed Russia’s defense industry, supply gaps opened. China quickly moved to fill them, and today it has become Algeria’s second-largest supplier, with a 14% market share.

Nigeria, ranked eighth, highlights China’s growing footprint in Africa. Between 2020 and 2024, China was the largest arms supplier in West Africa, with a 26% share, followed by France (14%), Russia and Turkey (11% each), and the U.S. (4.6%). But China’s role in Africa goes beyond sales figures.

Africa’s political landscape is defined by instability and recurring civil wars, where holding power often requires genuine military strength. Against this backdrop, military education has long been a pillar of China’s influence. The Nanjing Army Command College trained numerous African leaders, including Namibia’s former president Sam Nujoma, Tanzania’s former president Jakaya Kikwete, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s former president Laurent Kabila, Eritrea’s president Isaias Afwerki, and Guinea-Bissau’s former president João Vieira.

Many senior and mid-level officers from countries like Uganda and South Sudan have also studied at China’s Shijiazhuang Army Command College—now the Joint Operations College of the National Defense University—including both current and retired officers. Don’t underestimate these African officers trained in Chinese military academies; they could very well be the children of their country’s ruling elite, a general, or even a future president

In sum, China’s arms exports to Africa benefit from competitive pricing and flexible financing, reinforced by its deep economic and infrastructure ties across the continent. Just as important, Chinese weapons come with no political strings attached and a policy of non-interference—an approach that resonates strongly in politically sensitive West African states. By contrast, U.S. and Western suppliers often impose conditions linked to political reform and human rights, while charging higher premiums. Russia, meanwhile, is consumed by the war in Ukraine. Against this backdrop, China’s long-term positioning in Africa is beginning to translate into a clear competitive advantage.

In fact, as a ‘latecomer’ in the arms market, China has been finding opportunities to expand amid territories long dominated by the U.S. and Russia. International observers often mock that we only export to small countries—but isn’t that obvious? The two major powers have already divided up the big markets, and which weapons a country buys is primarily a political signal of alignment. The markets we can penetrate now are basically what we can extract from the pockets of these two big players—a gift of timing, geography, and strategy.

A broader point is that the focus isn’t just on who we sell to, but on actually getting our weapons into the field so they can be demonstrated in action. While we don’t fight proxy wars, seeing our equipment used in real operations is crucial. Publicly reported examples—like Egypt’s counterterrorism operations in Sinai (March 2017), the Iraqi government’s strikes against ISIS (2014), the Yemen Civil War (2016–2021), and the Libya Civil War (2019–2021)—all show Chinese drones in action. These smaller conflicts, which didn’t make headlines, verified the practical utility of our drones, gradually earning international acceptance and purchases. After all, people were initially skeptical of Chinese equipment, and this year Pakistan helped trigger a new surge of interest in our products.

China’s “Deepseek Moment” in the global arms trade

This moment can be called a ‘Deepseek’ moment for China’s arms trade—In the early hours of May 7, India and Pakistan fought an aerial battle lasting more than an hour. It was India’s deepest strike into Pakistani territory since the 1971 war. Despite India’s superior overall strength and its French-built 4.5-generation fighters, Pakistan’s air force—equipped with China’s J-10CE, the export version of the J-10C—emerged with a decisive advantage. Within minutes, the J-10CE shot down incoming Indian jets “like a phantom,” sparking a flood of commentary praising the aircraft’s prowess.

“Afterward, many people started saying how impressive our J-10 is, claiming: ‘Even though it’s older equipment, it’s so powerful, effortlessly taking down India’s French fighters and showcasing China’s might.’ But that’s not quite right. Let’s skip the hype and look at the facts.

The full picture is this: the J-10CE, together with PL-15 beyond-visual-range missiles and supported by the ZDK-03 early warning aircraft, forms a three-dimensional combat system covering early warning, targeting, and strike. It establishes an integrated land-and-air defense zone with roughly a 200-kilometer radius. You can think of the J-10CE as a semi-stealth missile launcher with its radar turned off—the missiles themselves are guided by the early warning aircraft, striking targets beyond visual range unexpectedly and significantly reducing the risk of enemy detection. That’s why I describe it as acting like a phantom.

Reports on the number of downed aircraft vary. Pakistan claimed it had shot down five: three French Rafales, one Russian-built Su-30MKI, and one MiG-29UPG. The tally may not seem high, but in a contest of systems against systems, the result was decisive. From the Indian perspective, their fighters were struck “before they even realized it,” leaving them in a state of confusion. Some accounts suggest India’s Rafales were primarily configured for ground-attack missions and not fully prepared for air combat. More critically, India’s air force operates a patchwork of Russian, French, and U.S. equipment, leading to poor data-link integration and a systemic disadvantage. Had Pakistan pressed further, it might have inflicted greater losses.

But warfare isn’t just about fighting; there are also political and social considerations. I’m not a current affairs commentator and won’t discuss India-Pakistan or China-U.S.-Russia relations. I just want to highlight that this demonstrates the practical combat capability of China’s ‘detect-and-strike’ system. During those days of sustained operations, the successful interceptions by our HQ-9 air defense system further showcased breakthroughs in China’s system-level warfare capabilities.

For years, China’s defense exports were dismissed by many major importers—partly for political reasons, and partly because of an enduring perception that Chinese systems were cheap and low quality. The recent event, however, was a turning point—a Deepseek moment—demonstrating that China can deliver not only advanced hardware but also a full-spectrum military solution. Purchasing the system effectively creates a 200-kilometer defensive bubble: within that radius, anything that enters risks being destroyed.

Unsurprisingly, the event drew global attention. Within a month of the clash, Indonesia’s deputy defense minister publicly confirmed the country was evaluating procurement of the J-10. The irony is striking: Indonesia had already signed a deal for 42 French Rafales and was in talks for U.S. fighters. Yet after watching Rafales shot down, it was natural for Jakarta to consider China’s system—more capable and more cost-effective—as an alternative.

According to Spain’s Defensa News, Colombia is also evaluating a potential switch to China’s J-10, with reports citing a base unit price of around $40 million and concessional financing on offer. China has already tabled a formal proposal for the sale of at least 24 J-10CE fighters. In the same month, Bangladesh was also reported to be advancing plans to procure 16 J-10CEs.

At roughly $40 million apiece, a 24-aircraft package approaches $1 billion in value—and that figure covers only the jets themselves, excluding associated systems and support. The case highlights how fighter aircraft, sold together with their integrated operational packages, have become China’s most commercially viable and premium-priced defense platform.

What does China sell the most?

So which category of Chinese equipment sells the most? Many might guess missiles—thanks to jokes about “missiles sprouting in the desert”—or perhaps drones, often portrayed as China’s high-volume, cost-effective exports. In reality, the answer is engines. Over the past decade, engines accounted for 51% of China’s arms export value, followed by aircraft platforms at 29%. Missiles and air-defense systems each made up just 6%, with all other categories barely registering.

For missiles, the leader is not China but the United States. In fact, aircraft are also the top source of U.S. export revenue, representing 58% of its sales, with missiles in second place at 19%.

Who buys America’s weapons?

Since we’ve mentioned the U.S., it’s worth pulling their numbers too. After all, critics often point out that China’s defense industry relies too heavily on Pakistan—a situation that in investment banking terms would be called “overexposure to a single client.” The concern is valid, but the U.S. faces a similar pattern.

America’s largest customer is Saudi Arabia, which accounted for 17% of its arms exports over the past decade. Other buyers—such as Australia, Japan, Qatar, and South Korea—pale in comparison, each representing only a fraction of Saudi Arabia’s purchases. The difference is that Washington’s top client share is not as disproportionately high as Beijing’s.

Between 2015 and 2024, the largest recipient of U.S. arms exports was Saudi Arabia (17.0%), followed by Australia (7.7%), Japan (7.3%), Qatar (6.0%), South Korea (5.4%), and Ukraine (5.1%). Other major destinations included the United Kingdom (4.3%), the United Arab Emirates (4.2%), Israel (3.5%), and Norway (2.9%). Together, these top ten markets accounted for a significant share of total U.S. arms exports over the period.

Where do China and the U.S. import their weapons from?

What about the other side of the equation—do China and the U.S. themselves import weapons, and if so, from where?

For the U.S., imports are negligible, a tiny fraction of its already massive exports. Its purchases mainly come from European partners such as the U.K., France, the Netherlands, and Germany.

Between 2015 and 2024, the leading suppliers of U.S. arms imports were the United Kingdom (18.0%, USD 1,302 million), France (13.0%, USD 911 million), the Netherlands (12.0%, USD 851 million), and Germany (12.0%, USD 823 million). Other major sources included Israel (10.0%, USD 726 million), Italy (7.0%, USD 499 million), Norway (5.6%, USD 399 million), Sweden (5.0%, USD 356 million), Australia (4.2%, USD 300 million), and Jordan (3.8%, USD 271 million).

China’s pattern looks different. Russia has been its largest supplier, followed by France, which primarily provides high-end components such as aircraft engines. The third source may be more surprising: Ukraine.

Between 2015 and 2024, the primary supplier of China’s arms imports was Russia (74.0%, USD 7,277 million), followed by France (11.0%, USD 1,110 million) and Ukraine (8.4%, USD 833 million). Other notable suppliers included Switzerland (2.0%, USD 195 million), the United Kingdom (1.9%, USD 190 million), Germany (1.8%, USD 176 million), and Uzbekistan (1.0%, USD 102 million).

China-Ukraine relations have historically been decent, with Ukraine serving as a crucial partner for China’s defense industry thanks to its inherited Soviet-era heavy industrial base. Naval propulsion was particularly critical: China imported Ukrainian gas turbines such as the UGT-25000 to power its 051C and 052C/D destroyers, filling a gap in domestic large-scale marine engines. In aviation, Ukraine’s Motor Sich supplied jet engines for the L-15 advanced trainer and provided helicopter engine support. The most emblematic case was in 1998, when China purchased the unfinished Soviet aircraft carrier Varyag from Ukraine. After years of modification, it eventually became China’s first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning. Other transfers included design data for the An-225 transport aircraft and technology related to air-to-air missiles.

At the time, Ukrainian arms sales to China carried fewer political restrictions, while Ukraine still retained significant technical strengths in fields China urgently needed, such as propulsion and shipbuilding. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s post-Soviet economy was chronically weak and in desperate need of cash. Once an industrial powerhouse within the Soviet system, it found itself adrift after the collapse, effectively selling off assets to survive. For China, securing this “great-power inheritance” at relatively low cost proved a bargain—allowing it to rapidly close critical gaps in aircraft carriers, marine engines, and related technologies.

Targeted imports, domestic breakthroughs

After 2010, China’s approach to weapons imports shifted toward small-batch, specialized procurement—purchases aimed less at filling arsenals and more at acquiring critical technologies. Buying fighter aircraft, for instance, was often about studying their engines; importing an air-defense system also meant dissecting its radar technology. China has continued to import certain core subsystems abroad to bridge gaps in domestic manufacturing.

Today, the balance has flipped: China’s exports are moving up the value chain, from low-cost, high-volume equipment to advanced, high-margin systems. In 2023, six Chinese companies ranked among the world’s top 20 defense firms, with the highest reaching No. 8. The global league tables are now dominated almost entirely by U.S. and Chinese firms, with only occasional entries from Russia and Europe.

One important distinction remains. For leading U.S. defense contractors, more than two-thirds—and in some cases over 90%—of revenue comes from weapons sales. By contrast, for Chinese firms the figure is far lower, typically 20–30%.

The relationship between U.S. defense contractors and the government is unusually tight. These companies depend heavily on government contracts, while US officials often rely on the industry for financial and career incentives. Legislators push policy and budgets; defense agencies define requirements and procurement processes.

Companies, through lobbying and personnel movement—especially the U.S.’s unique ‘revolving door’ practice—ensure contract awards and ongoing purchases, even involving key corporate personnel in policy-making itself.

Much of this cannot be spelled out openly, yet over decades it has built a stable ecosystem: America’s second-largest capital complex after finance, one sustained by constant conflict abroad. Under this model of “perpetual war,” it is no surprise that more than 90% of U.S. defense firms’ reported profits stem from weapons sales.

China’s defense industry, by contrast, is constrained by international politics but structured differently at home. Through a strategy of military-civil fusion, most Chinese defense companies also develop civilian applications—in electronics, machinery, and related fields—giving them more diversified revenue streams.

Although China’s defense industry has developed rapidly, its technological level still lags far behind that of the U.S., and the profit margins on Chinese equipment are much lower than those of American defense firms. Winning the current market through cost-effectiveness, lack of political strings, and long-term strategic planning is already a significant achievement.

The recent “Deepseek moment” may mark a turning point, sparking a new wave of demand. While the overall scale of our arms trade still falls far short of challenging the U.S., the limited markets we have tapped provide more Chinese equipment with real-world operational opportunities. In today’s volatile global environment, the test is whether Chinese equipment can move beyond its old reputation for being “cheaply made” to one of being “affordable and reliable.”