Why Baidu is facing its biggest crisis in the AI age

AI is polluting the internet, and its impact in China is unlike anywhere else

AI is polluting the Chinese internet

I’ve been using ChatGPT—and subsequently, other large language models—since the early release of GPT-3.5. Since then, my workflow has changed forever: writing, researching, coding, even personal learning—everything is faster and more efficient. But as I’ve written more with AI, I’ve also developed a sixth sense for spotting AI-generated content. I can’t explain it with hard rules, but the intuitive "pattern recognition" is real. You just know when something smells like it was churned out by a model.

And that smell? It’s becoming increasingly common. What we’re witnessing is a rising wave of AI-generated digital pollution—content that looks polished but is factually empty, emotionally manipulative, or just outright false. This isn't just noise; it's a dangerous feedback loop: people generate low-quality content with AI, that content spreads, gets scraped back into training datasets, and in turn, makes future models worse. It's a self-reinforcing spiral of junk.

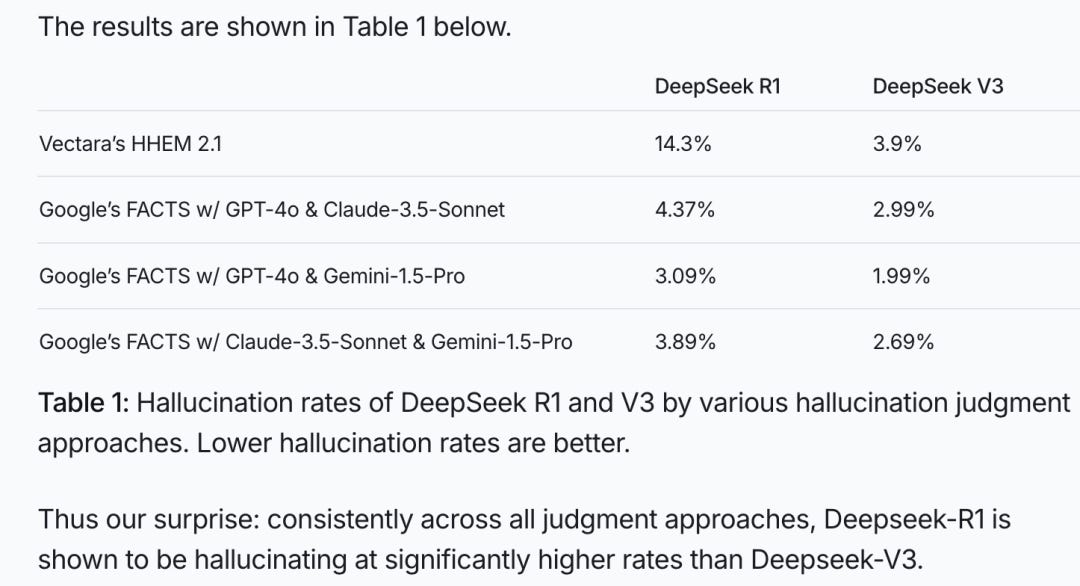

Take DeepSeek-R1, one of China’s most-hyped LLMs, as an example. Despite the buzz, it has a whopping 14.3% hallucination rate, according to Vectara (an AI solution company focusing on AI reliability and accuracy)—nearly four times higher than the previous DeepSeek-V3 model.

A recently viral article in the WeChat community, titled “DeepSeek’s Fabrications Are Drowning the Chinese Internet,” has spotlighted several instances of AI “polluting” the Chinese internet. At least three popular articles that went viral on China's major social media platforms such as WeChat and Zhihu (China's equivalent of Quora) were actually generated by DeepSeek-R1 and rife with factual errors.

For example, a Zhihu post that has garnered over 7,000 likes and delves into the behind-the-scenes story of China's latest blockbuster animated film Nezha 2 serves as a case in point. On the surface, the post appeared to be well-constructed, evocative, and rich in data, seemingly airtight. However, it was nothing more than pure AI-generated fiction. The article asserted that Ao Bing’s (one of the protagonist characters) transformation scene in Nezha had impressed audiences at the Annecy International Animation Festival in France. It sounded persuasive, yet it was entirely untrue.

In the article“DeepSeek’s Fabrications Are Drowning the Chinese Internet”, the author said:

I was just like him at first—excited about the rise of Chinese animated films and completely convinced by what seemed like a well-argued, fact-filled piece. But one fatal error made me realize something was off.

The article claimed that Ao Bing’s transformation scene in the Nezha movie stunned audiences at the Annecy International Animation Festival in France. The problem? While Annecy is a real festival, and Nezha was indeed submitted there, it was New Gods: Nezha Reborn by Light Chaser Animation—not the well-known version directed by Jiaozi. And that submission was only a modern, urban-themed racing short—Nezha and Ao Bing didn’t even appear, let alone cause a sensation.

What’s most disturbing is that the AI-generated piece didn’t have any obvious “AI flavor.” No random gibberish. The structure was smooth, even the rhetoric was quite polished. It likely came from a well-crafted prompt—or someone manually edited it afterward.

This is the face of "AI's digital contamination": machine-generated nonsense, served up with confidence, and consumed by humans who believe, repost, and emotionally engage with it. This also serves as yet another illustration of the view I expressed in last week's newsletter "Three 'bad news' for Chinese tech stocks": China’s AI ecosystem still has a long way to go, despite the hype around players like DeepSeek. We shouldn't rush to idolize them.

However, the impact does not await technological advancement. AI-generated content is already influencing netizens in very tangible ways—what we read, what we believe, and how we talk about the world around us.

And the scariest part is that most people won’t fact-check. We won’t even think to fact-check. Because when AI speaks with clarity and confidence, it sounds like truth.

Baidu's problem (NASDAQ: BIDU)

AI hallucination isn’t a China-specific problem—but the stakes and context in China are quite different.

For companies like Baidu, China’s equivalent of Google, it’s an existential crisis. Google, despite rising competition from AI-native search engines like OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Perplexity, still has a way to stay in the game: it can integrate AI-generated answers directly into its search results. I’ve also noticed Google’s been sneakily boosting actual human content—Reddit posts, for example, are increasingly ranked higher. (Probably because Reddit is one of the last corners of the internet where real people still hang out and type things.)

But Baidu is getting hit by both sides. First, its search results are rapidly being flooded with unchecked, AI-generated junk—content produced at a scale no human team can match. Second, most of China’s high-quality, human-generated content lives in closed ecosystems like WeChat and Xiaohongshu (the Red Note)—platforms Baidu can’t effectively index.

Personally, I’ve almost stopped using it entirely. For technical, analytical, or in-depth information, I usually turn to WeChat search. For lifestyle, travel, food, or everyday how-tos, Xiaohongshu is my go-to.

Tencent has integrated DeepSeek into its WeChat Search. Now you can conduct AI searches in a database of millions of articles and videos created by 1.3 billion WeChat users.

The irony is hard to ignore: Baidu, once the backbone of China's information web, is being made obsolete by the very AI technology it's racing to develop—and outflanked by companies like Tencent and Xiaohongshu, who never set out to build a search engine in the first place.

Monetizing AI in China’s internet ecosystem

The difference between China’s and the U.S.’s internet ecosystems is hard to ignore. In China, tech giants are far more integrated—they’re building both the large language models (LLMs) and the downstream applications that dominate consumer attention. Tencent, for example, has access to a massive user base (the entire China population) via WeChat. Alibaba owns both the e-commerce and digital payments space. This kind of vertical control is rare in the U.S., where most leading AI startups focus almost exclusively on developing the model itself.

In that sense, Meta is one of the few exceptions—it has a strong position in both LLM development and user traffic. Amazon also has the potential to build in-house LLMs and integrate them across its e-commerce empire. Still, these are nowhere near the level of integration we see in China. In China, apps like WeChat or Alipay basically do everything—shopping, payments, loans, mortgage management, restaurant bookings, even medical appointments. You basically live in WeChat and Alipay. The downstream AI use case potential is enormous.

In contrast, the U.S. market is more fragmented. That’s actually an advantage for small and mid-sized companies. With no single super-app dominating every layer of the user experience, there’s more room for startups to build AI tools tailored to specific workflows or sectors. Even if they’re just wrappers around existing models, they can still add real value.

But in China, the structure of the ecosystem strongly favors the tech giants. Companies like Alibaba, Tencent, and content platforms (namely, Xiaohongshu, Douyin, Kuaishou) are the clear winners. They own the user-generated data—most of it trapped in their private domains—and most of them are now building their own LLMs in-house. Alibaba can directly integrate its LLM into Taobao or Tmall, and it will handle all your advertising, purchasing, customer analytics, sales, and marketing campaigns in both B2C and B2B scenarios. In the U.S., that same functionality might be spread across a dozen different startups offering SaaS tools to marketplace sellers and advertisers.

As I mentioned in a previous newsletter, China’s AI commercialization path is still largely experimental. Ironically, the people making the most money from AI so far aren't building tools or products—they're selling courses. One telling case (which I covered in this newsletter): a Tsinghua-educated PhD made a fortune selling low-quality AI training courses, only to be removed from the internet after fraud complaints. Still, it says a lot about where demand is in China—education over real application.

Right now, one of the few clear commercialization paths for AI in China is e-commerce.

Back in July 2023, I wrote about how merchants in China were already replacing human livestreamers with AI-generated digital avatars, costing as little as ¥400 (~$56 USD) per avatar. These aren’t just experiments—they’re driving real sales, albeit products sold by AI hosts are usually cheap utility products.

No surprise then that when Zhipu AI—one of China’s top three LLM unicorns—launched its AI agent AutoGLM last month, it heavily promoted e-commerce as a core use case. AutoGLM is pitched as a human-like intern that can browse the internet and complete basic tasks. They even demoed it running a Xiaohongshu account, gaining 5,000 followers in two weeks and closing a deal. This, for now, is one of the clearest paths to AI monetization in China.

Last month, when I went home to visit my 60-year-old dad, he proudly showed me a Xiaohongshu account he’d been following. It was all interior design and home furnishing content—gorgeous spaces, scenic views, tons of likes and shares, and shopping links on the main page. However, what he didn’t realize was that every image was AI-generated. That’s when it really hit me: AI isn’t just coming—it’s already here. And in China, e-commerce is hands down the most proven path to monetization.

Which brings us back to Baidu. Unlike Alibaba, ByteDance, Kuaishou, or even Xiaohongshu—companies that already sit at the intersection of user content and commerce—Baidu has neither. No real social presence, no e-commerce pipeline, and very little access to private domain data. The company that once led China’s internet revolution may now be looking straight at irrelevance.

That’s all for today. Now, readers of Baiguan—take a wild guess how much of this newsletter was written by AI 😉.

"People don't fact check"

To some extent, I think this is a learning curve. Like I had to learn to fact check journalists, even those from established newspapers. After all, to some extent, surely AI is no less reliable than Fox News, MSNBC, NYT (on Gaza) or SCMP (on Chinese science). And many people still take what these outlets have to say as reliable. I still see serious papers and articles that still quote news articles on China's social credit system or China's debt trap for Africa as their reliable research sources for the "truth" of these "facts". LOL. AI cannot be MORE reliable than these "standard bearers" of "truth" surely.

I appreciate that this "inaccuracy" is different from making up facts or hallucinating, but at the end of the day, whether it is a human making up facts by telling a lie (bogus research or politically motivated propaganda masquerading as news) or whether it is AI making up facts by hallucinating, the end result is the same: you need to either fact check or discount until proven true.

What I am interested in is whether it is even remotely possible for AI to be accurate and not hallucinate, given that AI has no way of establishing facts on its own. It does not know what constitutes facts, cannot refer to or assess primary material and sources, and does not have a system for assessing accuracy of anything that is fed to it. So how can it be possible for AI to ever be useful as a definitive research tool?