From “Exit” to “Rebound”: Rethinking the Investability of China’s Capital Market

Horizon Insights Research Series #4

Today, we’re excited to share another insightful guest post from our partner Horizon Insights, a respected independent research provider based in Shanghai.

Since 2021, one of the most heated debates in global finance has revolved around a single question: Is China’s capital market still “investable”?

In the years following COVID, that debate was driven largely by pessimism — foreign capital retreating, a sluggish domestic economy, and rising geopolitical risks.

Yet, as the environment changes, the nature of the debate is also shifting. This year, China’s onshore and Hong Kong markets have been among the best performers globally. The question now is no longer just whether China’s market is investable — but how sustainable this rally really is, and what new factors investors should watch to judge China’s long-term investment potential.

In this piece, Horizon Insights unpacks the complexity of investing in China’s capital markets, analyzing the key dimensions investors should watch. It also explores the fundamental forces shaping China’s medium to long-term investment outlook.

You may also want to check out Horizon Insights’ equity coverage list, and their sample reports.

The following article is by Dongfan Ma, Founder & Chief Strategy Analyst at Horizon Insights.

Preface

Since 2023, one of the hottest debates in the investment community has been about the investability of China’s capital market—especially whether the Chinese stock market is still “worth investing in.” With foreign capital continuously withdrawing and domestic investors remaining cautious, the dominant narrative over the past two years has been that “China’s market has lost its investment value.” But the reality is far more complex. In this essay, we explore China’s capital market’s investability from two dimensions:

a) Understanding the structure, volatility, and return logic of China’s market from its internal operational characteristics.

b) Analyzing China’s current economic stage—its growth model, innovation capacity, and institutional advantages.

In other words, we must look not only at how the market moves, but also why the economy moves the way it does. Only by understanding both dimensions can we truly answer the question: Is China’s market still investable?

Part One: The Structure and Logic of China’s Capital Market

Over the past decade, China’s capital market has exhibited characteristics distinctly different from most global markets. It is both highly liquid and extremely volatile, with rich differentiation in returns. These features do not imply inefficiency or disorder; rather, they define a market that demands understanding of structure and rhythm.

1. Retail-Driven Sentiment Cycles

Over the past ten years, the annualized EPS growth rate of the overall Chinese market has been around 8%, slightly below GDP growth but broadly consistent with long-term trends. One unique feature of the Chinese market is the dominance of retail investors.

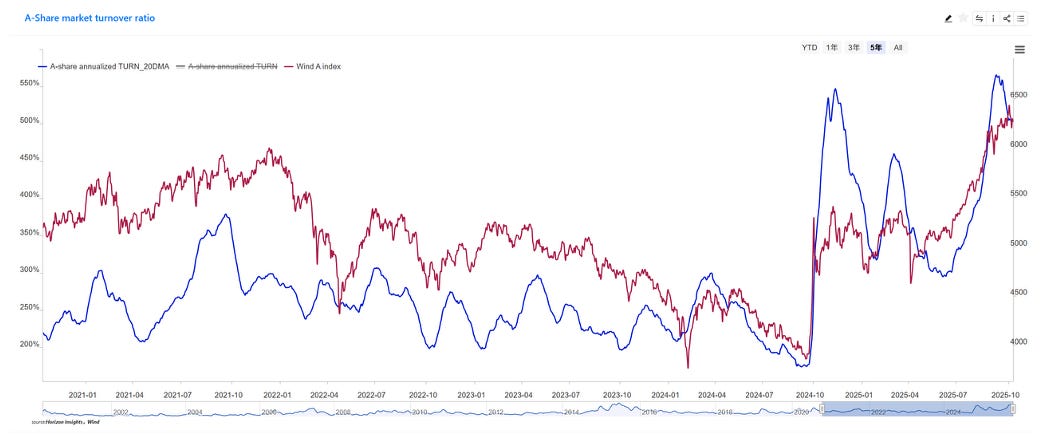

Currently, the daily turnover ratio hovers around 500%. In a market exceeding 100 trillion RMB, this implies an extremely short average holding period. Quantitative funds and retail investors together drive the majority of market activity.

This leads to two outcomes: short-term volatility far exceeds that of overseas markets, and within that volatility lies a wealth of short-term signals.

For example:

When turnover rises, it often signals a short-term market peak; when turnover falls, it tends to mark a short-term bottom. This roughly two-month turnover cycle forms a typical emotional fluctuation cycle in the Chinese stock market. For institutions with trading strategies and execution capability, such volatility is not a risk—it is an opportunity.

2. Mid-Cycle: The Resonance of Valuation and Earnings

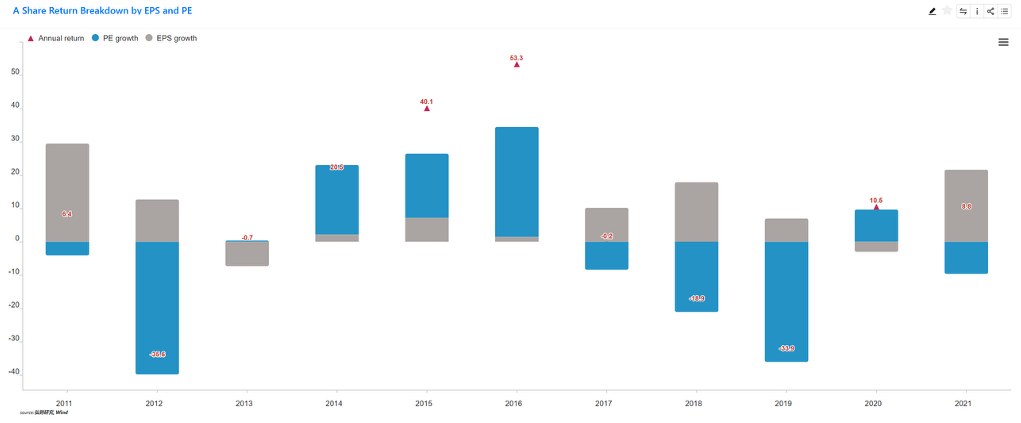

On a medium-term horizon of one to three years, market fluctuations are closely tied to economic growth. If we decompose market movement into “EPS changes” and “valuation changes,” we find that:

At an annual level, valuation swings dominate in most years, while earnings growth (EPS) determines the mid-term trend.

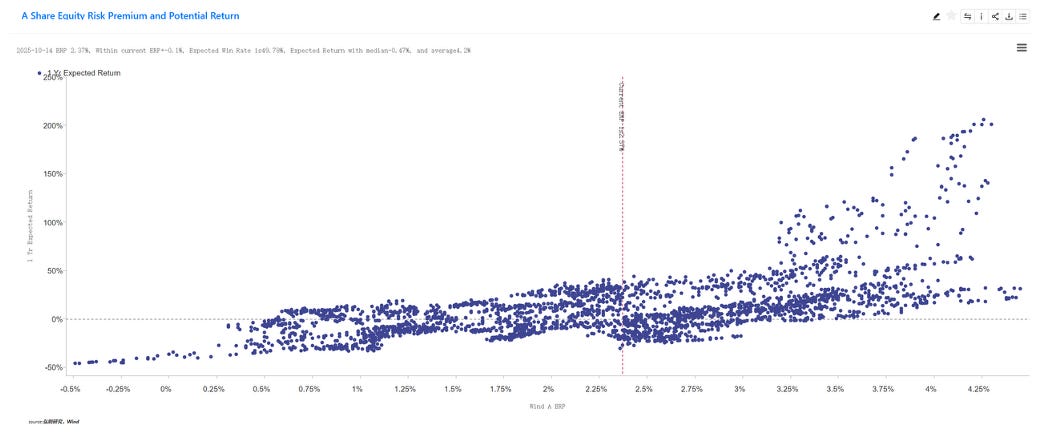

Therefore, valuation levels are the key indicator of investment success in the mid-cycle. The lower the valuation, the higher the future payoff. For instance, by the end of 2024, valuations implied very high probability-adjusted returns, whereas in 2021, they indicated very low odds. This demonstrates that cyclical volatility contains structural opportunities for excess returns.

Through ERP (Equity Risk Premium) calculations and high/low assessments, we can clearly observe directional market signals across 2019–2025.

3. Long-Term Structure: Low Household Participation and Policy-Driven Supply Cycles

Over the longer term, China’s capital market differs from mature global markets mainly in two ways: household participation remains low, and market supply follows a policy-driven cycle.

Household asset structure:

As of 2024, Chinese household deposits amounted to about 150 trillion RMB, while only around 30 trillion RMB sat in brokerage accounts, with total equity assets near 40 trillion RMB. This means household participation in equities remains relatively low, leaving significant room for future growth.

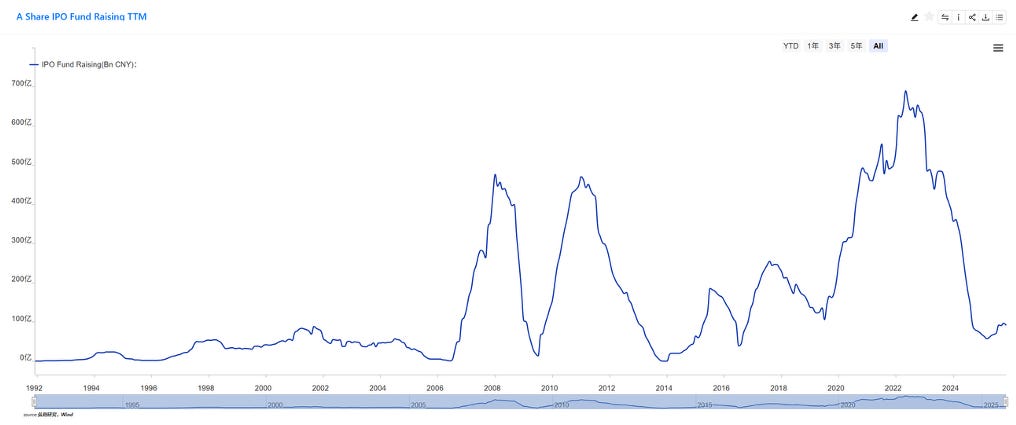

IPO regulation cycle:

China’s IPO rhythm follows a clear policy-driven pattern: when markets perform well, supply increases; when markets weaken, supply tightens. This often leads to “insufficient stock supply and continuous capital inflows” during market bottoms—laying the foundation for rebounds.

Over the past 15 years, Chinese stock EPS growth has lagged GDP mainly due to the dilution effect of equity financing. Historically, the capital market has been geared more toward financing functions than investment returns. But with policy reforms and capital structure optimization, this trend is gradually improving.

In summary, China’s high volatility, periodic drawdowns, and long-term performance divergence do not indicate “un-investability.” On the contrary, they provide fertile ground for professional investors who understand structure and cycles to capture alpha.

Part Two: China’s Economic Stage and Growth Logic

To understand China’s capital market, one must look beyond market fluctuations to the economic structure beneath them. The logic of China’s economic growth is shifting—from external stimulus to internal innovation-driven forces. This transformation is the key determinant of future investability.

1. From “Resource Input” to “Innovation-Driven”

Traditional growth models (like the Solow model) emphasize the roles of capital and labor inputs. However, recent Nobel Prize-winning research highlights disruptive innovation as the true source of long-term growth.

In China, this innovation-driven transformation is particularly evident. Even amid the downturn in real estate and weak external demand, technological progress, educational advancement, and institutional innovation continue to sustain growth.

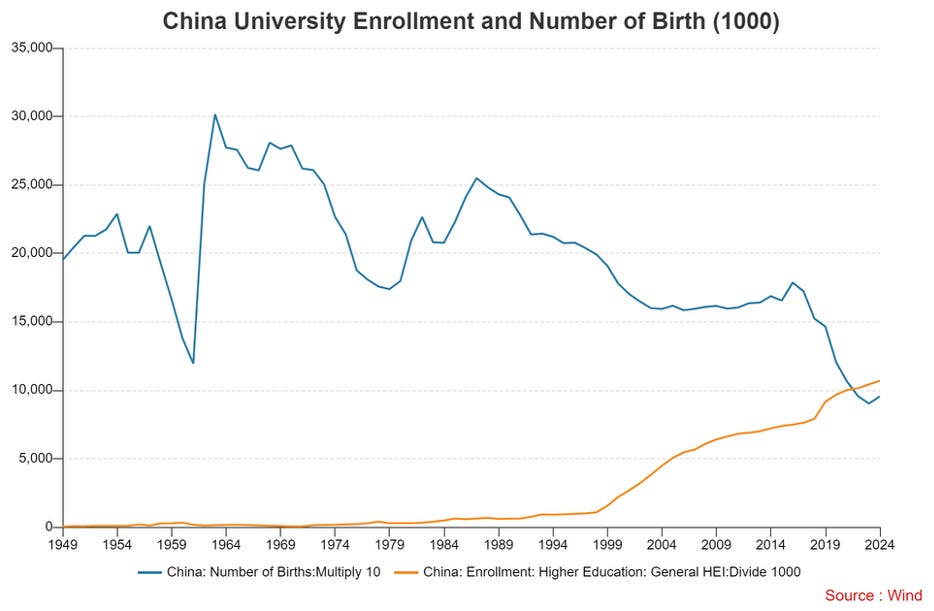

Education is the core variable behind China’s economic transformation. In 2000, the average years of schooling among the working population was 7.85 years; by 2015, it had risen to about 9–10 years; by 2025, it is expected to reach 10–12 years. The new labor force now averages 14 years of education (undergraduate level), meaning roughly half of new entrants hold university degrees.

This educational advancement directly fuels industrial upgrading and technology diffusion. The rapid rise of sectors such as AI, innovative pharmaceuticals, robotics, new energy, internet applications, materials science, and semiconductors reflects this structural dividend.

China’s growth model is gradually detaching from dependence on real estate, debt, and external demand, and shifting toward an endogenous model driven by education, research, and innovation. This gives China stronger resilience, shorter cycles of fluctuation, and greater long-term potential.

2. China ≠ Japan: A Misread Analogy

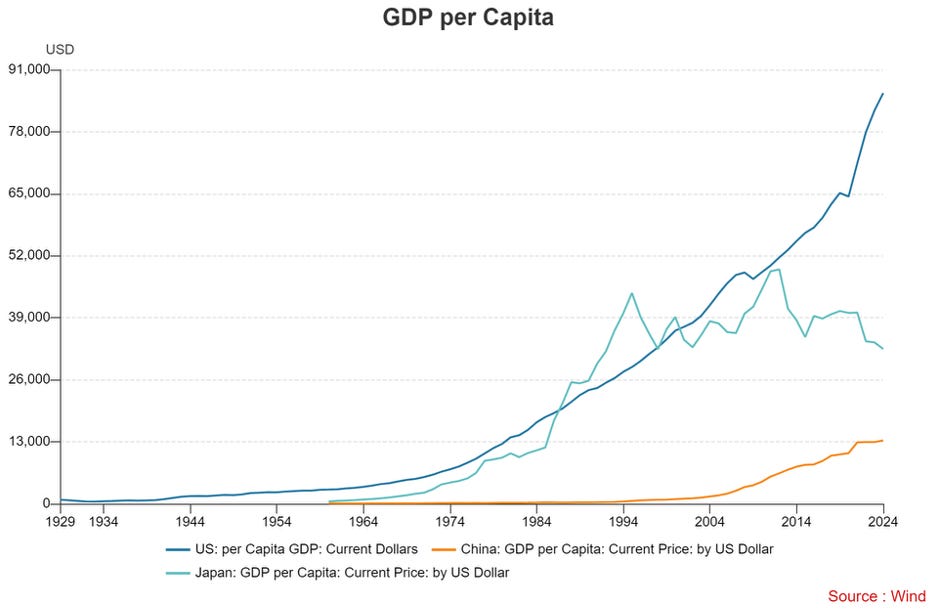

In recent years, many investors have compared China to Japan in the 1990s, suggesting it may face a “lost decade.”

But this analogy misses crucial differences. Japan’s long stagnation fundamentally stemmed from a breakdown in its technological trajectory. During the major waves of the PC, internet, telecommunications, and renewable energy revolutions, Japan was largely absent, while the U.S. and later China became the key beneficiaries.

Today, China remains in the ascending phase of its innovation cycle. Its per capita GDP is only one-seventh of that of the U.S., but its educational attainment, R&D investment, and technological innovation are rising rapidly.

Therefore, China is far from entering a “technological stagnation period.” On the contrary, it is at the early stage of innovation-driven dividends being unleashed.

For inquiries or collaboration, contact us by replying to this email or at: subscribe@hzinsights.com

About Horizon Insights —Established over a decade ago, Horizon Insights is dedicated to delivering in-depth, cycle-aware insights into Chinese assets. Our core team comprises well-regarded investment research professionals who have been working closely together for almost two decades and have earned the trust of over 1,000 institutional and professional investors worldwide. Our research is recognized for its independence and foresight, grounded not in noise but in long-term conviction and depth. We’re grateful to connect with you through this Newsletter, and we look forward to ongoing, thoughtful dialogue.