How is inland migration reshaping China's economy?

Middle class turmoil, lower-tier city boom and parallel US-China phenomena

In the era of China's rapid economic boom, people flocked to first-tier cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, chasing opportunities for upward mobility and a better life, a phenomenon dubbed "drifting." These urban wanderers braved high pressures and living costs, leaving behind families for the promise of a brighter future. However, as the economy slows and opportunities in these metropolises dwindle, the middle class, once the engine of high-end consumption, now finds itself burdened by financial strains—high leverage, shrinking wealth, and the dual responsibilities of children's education and elderly care. Consequently, many are seeking to escape the hustle of the big cities.

The future of China's population movement, as we've previously discussed, is shifting towards mid-tier cities. These regional centers, with their manufacturing hubs and relatively affordable living costs, offer job prospects and decent incomes. Today, we bring you an article by Baiguan's old friend Bob Chen, published on his personal WeChat blog, detailing his insights from conversations with entrepreneurs and industry professionals, as well as macro data, to map out the current trajectory of China's economic decentralization.

Below is Baiguan's translation of the original article (some paragraphs are abbreviated or redacted).

Real-life observations: shifting tides in various industries

Recent discussions with entrepreneurs and industry professionals highlight a growing trend of individuals moving back from first-tier cities. The reasons for this shift are varied and numerous, including:

Cross-border e-commerce practitioners in Shenzhen are finding that the high living costs are too taxing. After paying for rent, they find themselves with a modest income, insufficient to purchase property, or plan for long-term stability. Rather than burning out by 35 in the so-called "talent mines," they are opting to return to their hometowns in Hubei or Hunan Province, leveraging their experience and supply chain connections to open Amazon stores. They don't aim for vast wealth, but after initial investments, making a few thousand yuan a month is more than enough to live comfortably in a third-tier city, especially with free housing and family support for meals.

Entire cross-border e-commerce teams are relocating to inland areas. Local governments are eager to fill the creative industrial parks built a few years ago, and they also need local programmers and students majoring in foreign trade. Labor costs plummet by over half, and companies no longer have to deal with constant poaching from competitors and high employee turnover.

A North American software company has set up its R&D team in a surprisingly remote inland city with few academic resources. The company found a surplus of programmers, indicating that talent is not exclusive to metropolitan areas. The main requirement was a product manager to oversee product design and a capable leader to manage a team of engineers, many of whom hold associate degrees.

An employee from a fund in a first-tier city was recently laid off and has returned home to inherit a small family business in the Yangtze River Delta, running a factory or simply "lying flat," a term used to describe a more relaxed approach to life and work. Some parents, who were originally planning to sell off their equipment, have allowed their children to take over the reins, but with limited expectations.

Aligning macro data with micro observations

Population flow shifts reversely to inland areas: shrinking job opportunities, declining rent in high-tier cities

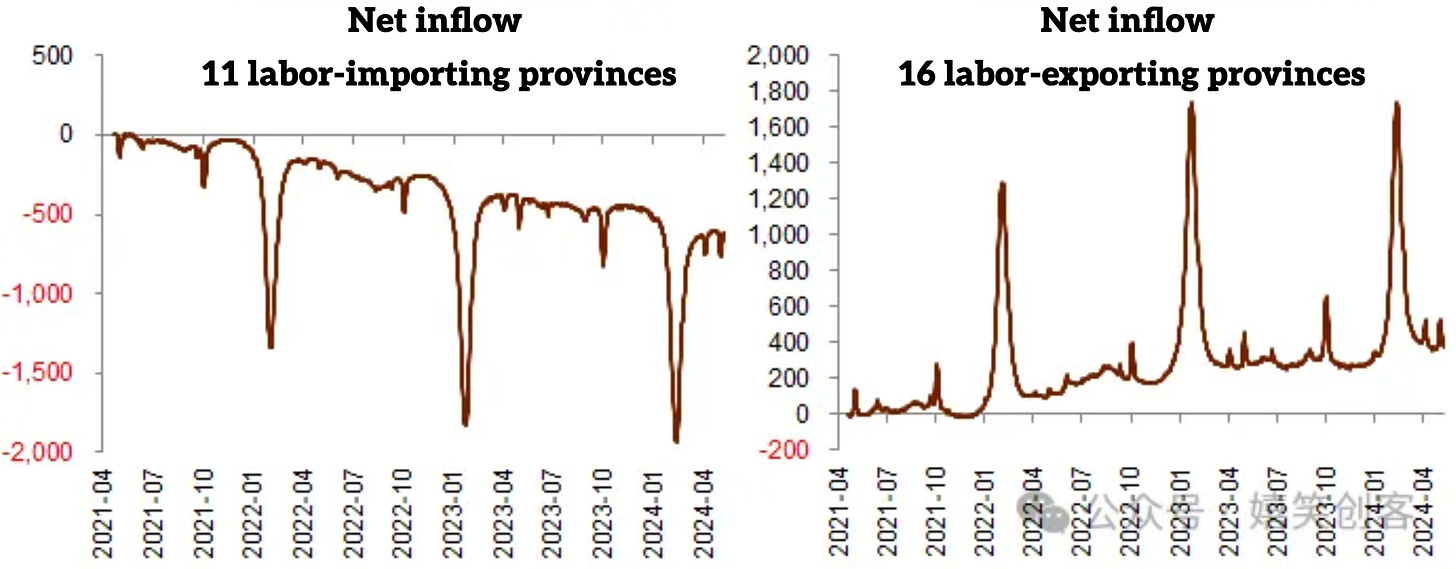

As migration flows shift, people are moving back to third- and fourth-tier cities, causing a net inflow into labor-exporting provinces and a net outflow from traditional migration hubs. The long-debated "escape from Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou" didn’t materialize during the boom years but is now becoming a reality in this period of economic downturn.

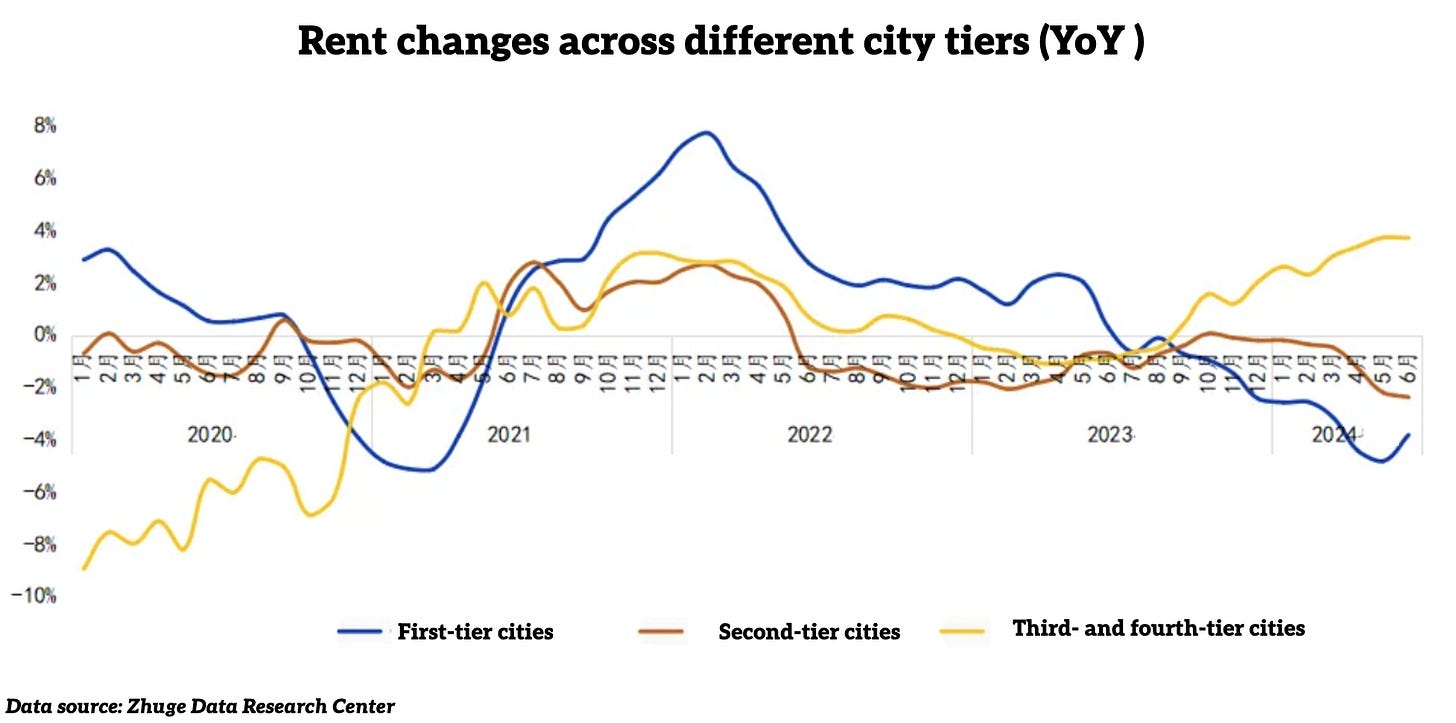

Therefore, the growth rate of rent in third- and fourth-tier cities has outpaced that of first- and second-tier cities.

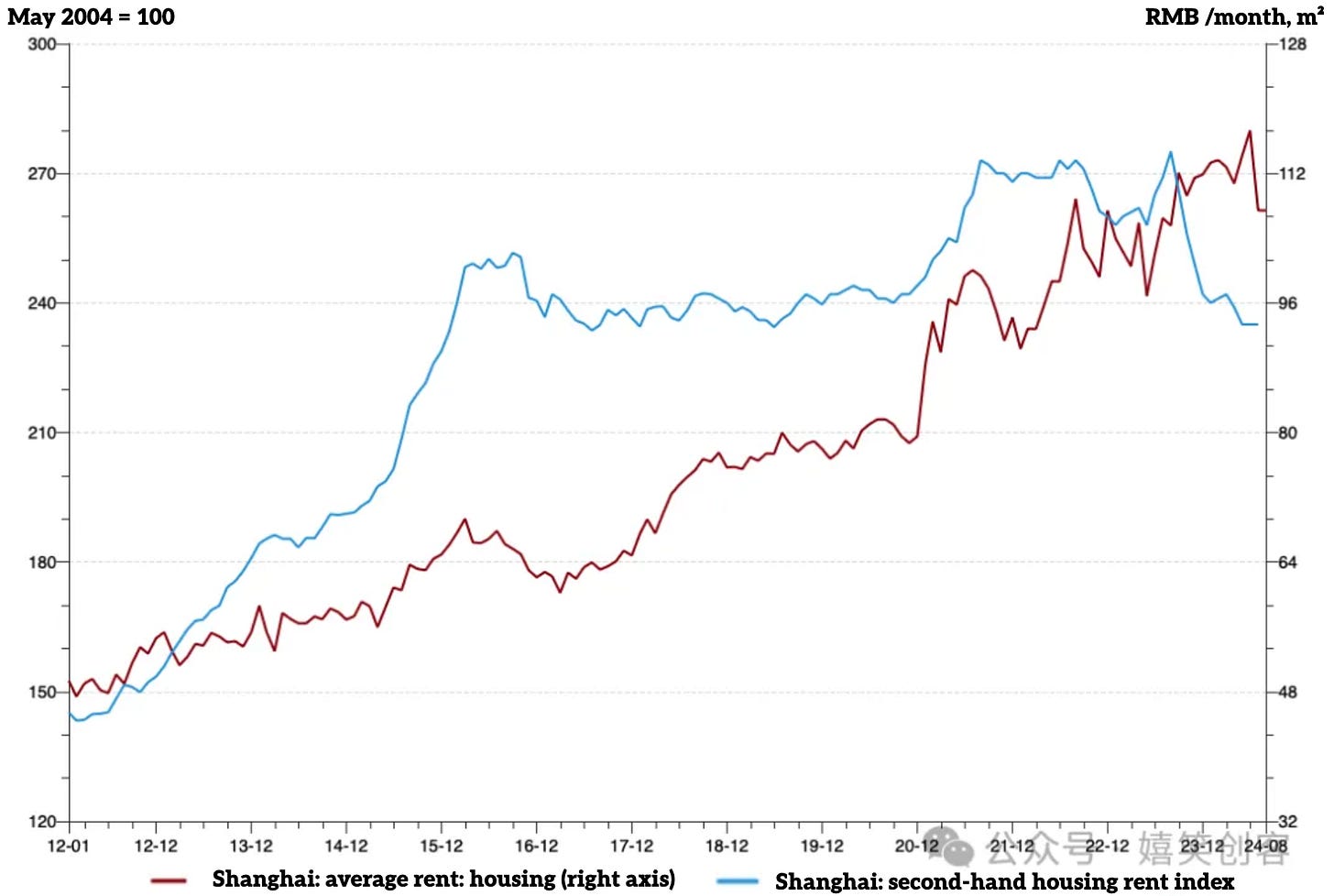

While rent in first-tier cities has indeed decreased, job opportunities are shrinking even more rapidly. More importantly, the prospects for those who remain have dimmed significantly, if not vanished entirely. This mirrors the challenges faced by the food and beverage industry, where despite rigid rent costs, both customer traffic and average spending per customer have declined more sharply, directly squeezing profits.

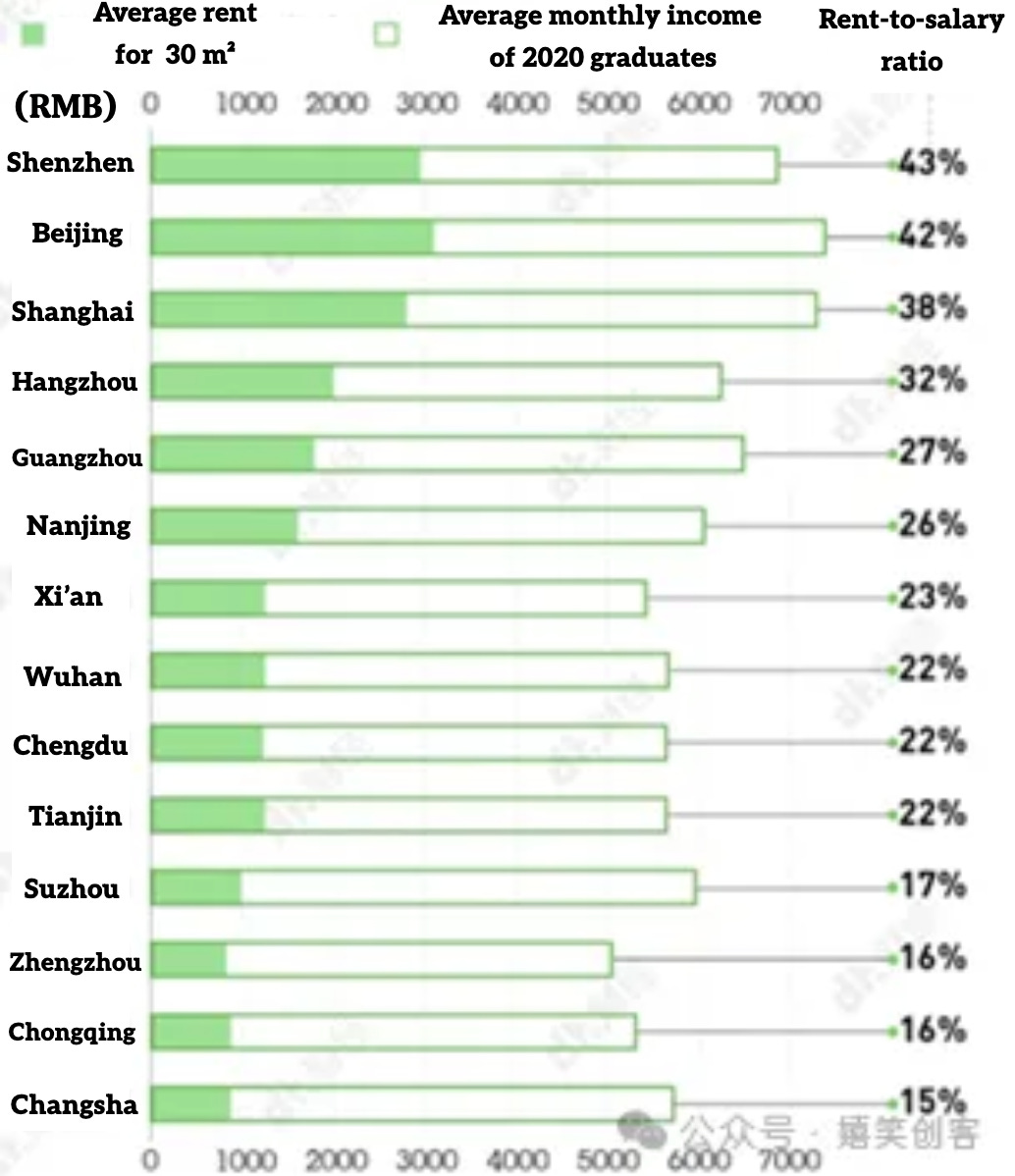

Rent and housing prices remain inflexible. Recent graduates are the most mobile, but also the least likely to settle down, as rent consumes nearly half of their income. Rising youth unemployment reflects a reluctance among companies to invest in new hires. Meanwhile, many business owners, especially those without debt pressure, are considering exiting the market themselves.

Individualized operations in the F&B industry could be a growing trend

Trends in the food and beverage (F&B) industry not only reveal city-level differences but also indicate the higher potential of individualized operations. In the first half of 2024, Beijing's F&B sector experienced a significant year-on-year decrease in total profits, dropping by a staggering 88.8%. The situation in Shanghai was even more dire, with operating profits turning negative.

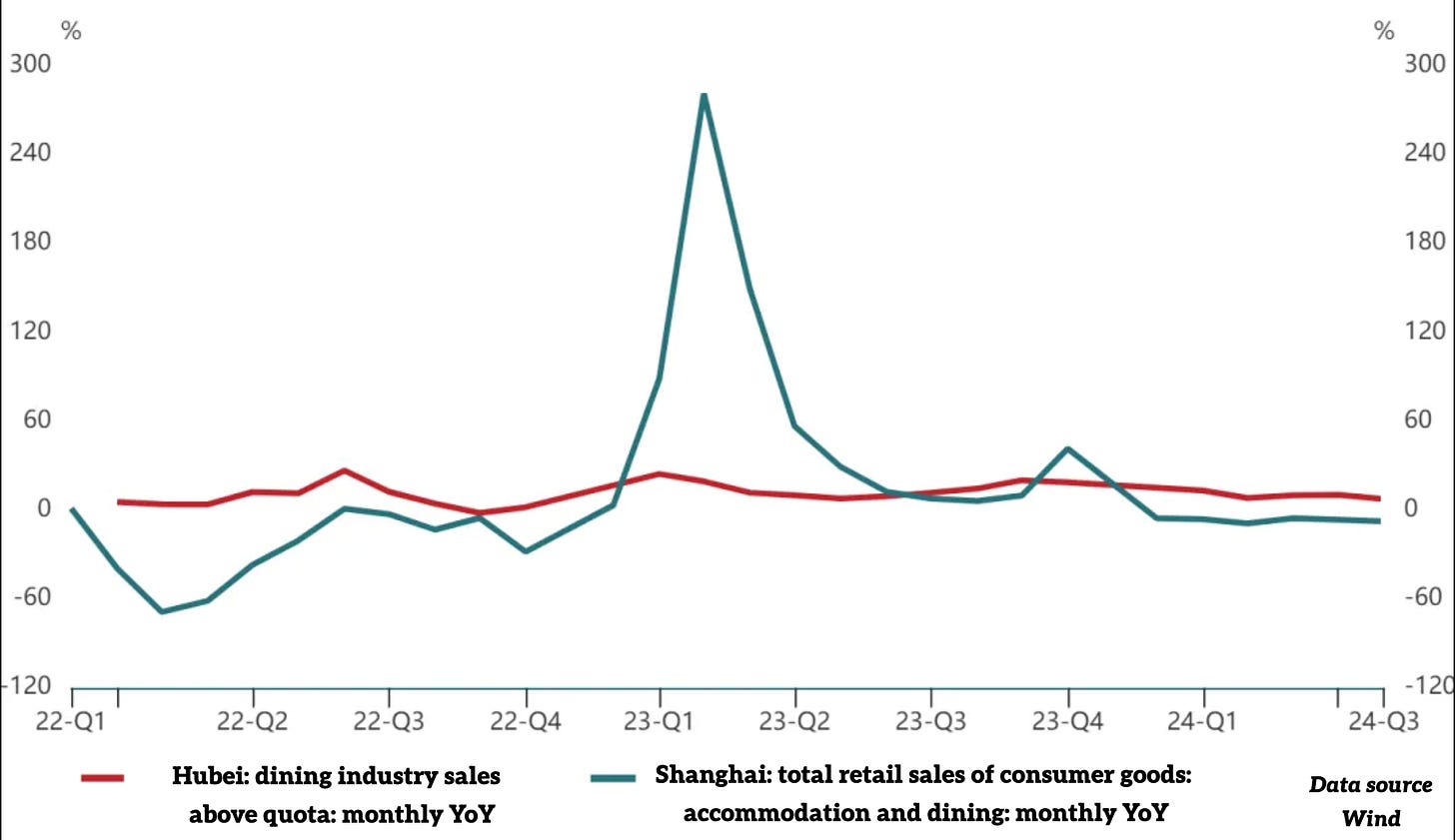

A comparative analysis of two randomly selected regions, Shanghai and Hubei, shows that the latter has maintained a more stable growth trajectory. Indeed, Hubei's growth has consistently outpaced Shanghai's for some time now.

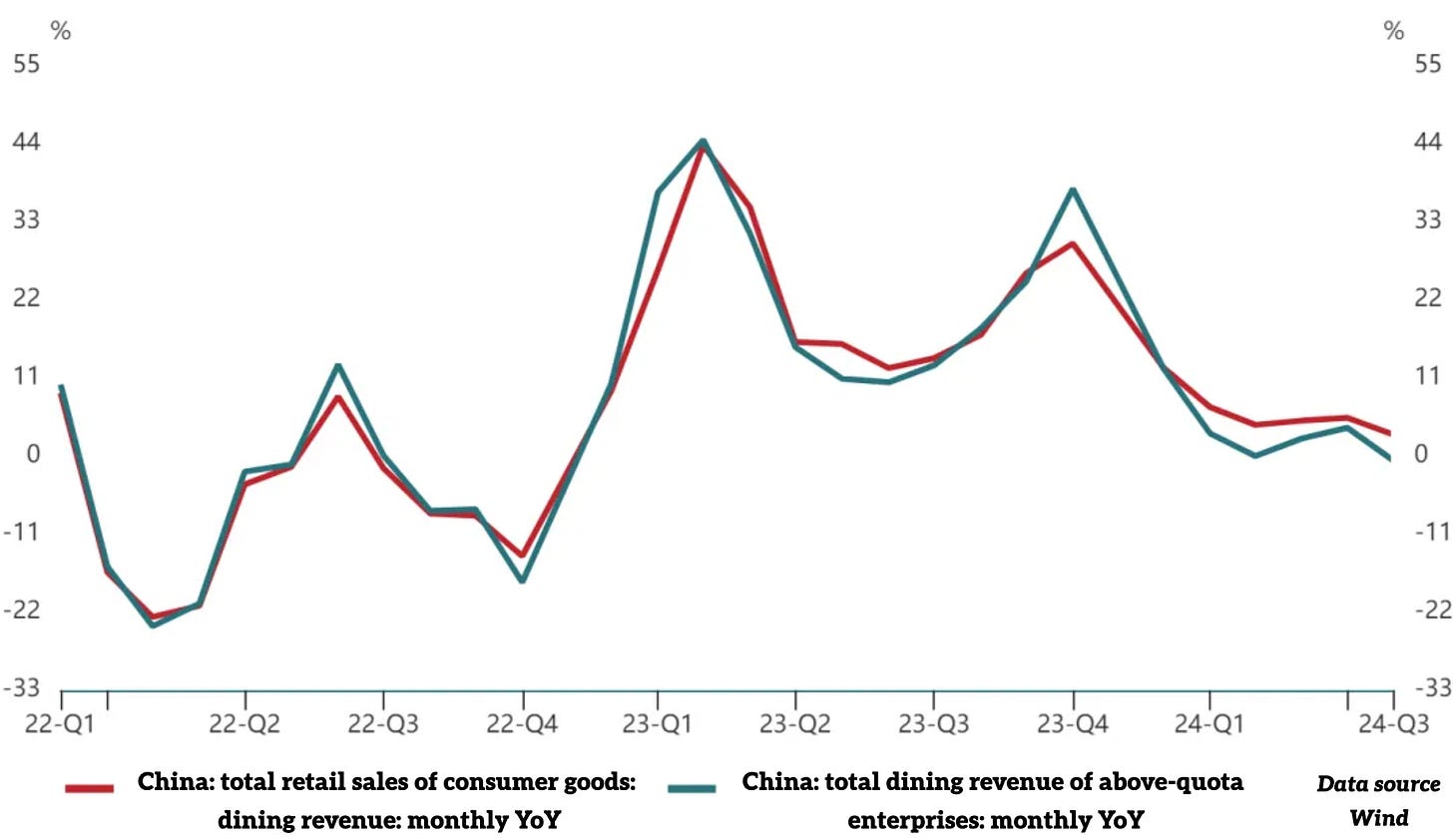

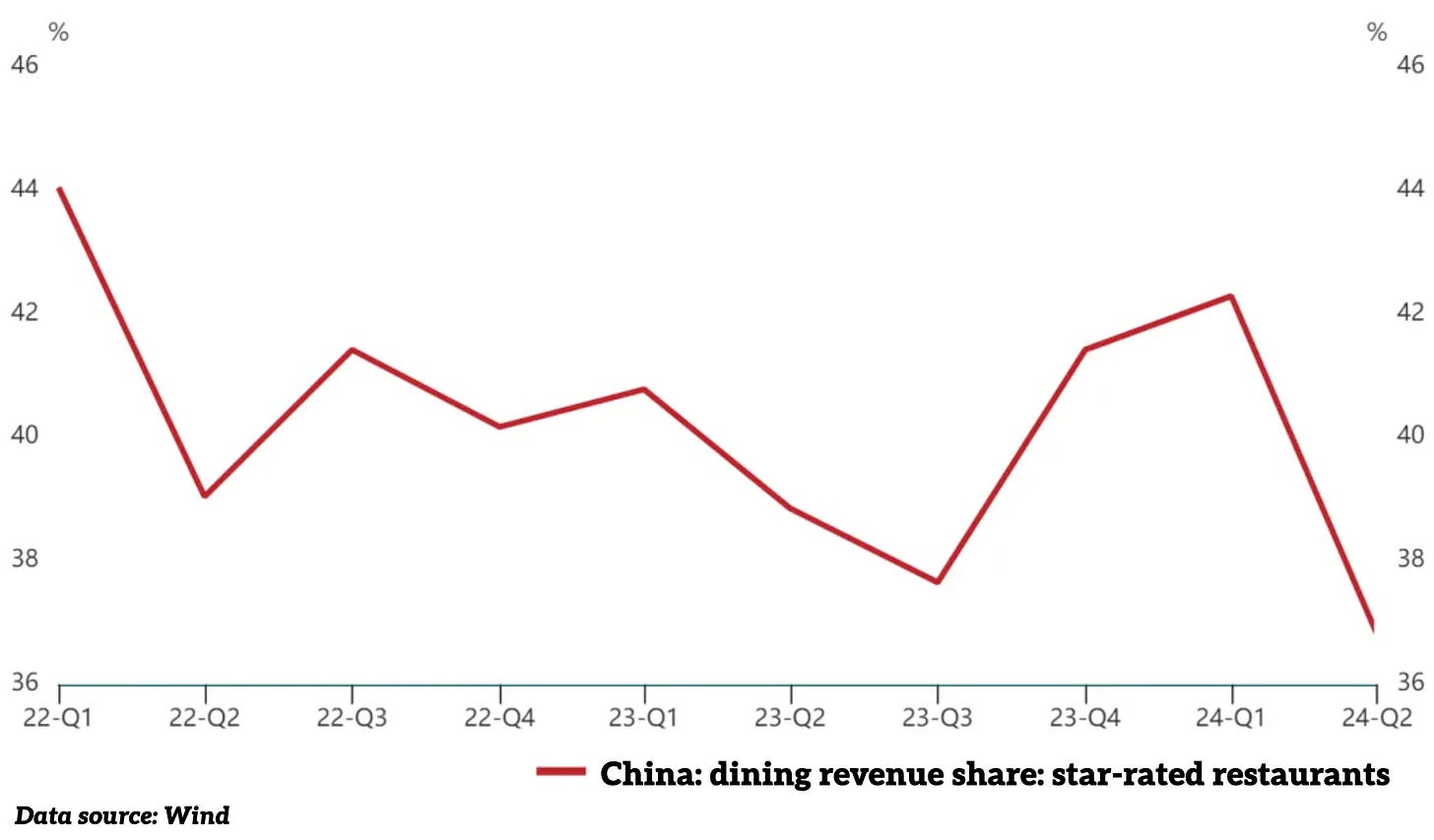

Beyond the urban disparity, according to National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) data on catering revenue, large and medium-sized catering businesses have experienced a steeper decline compared to smaller operations. Additionally, the revenue share from star-rated restaurants within China's catering sector has been on a significant decline. This is likely due to the fact that larger companies carry a heavier burden of fixed costs.

This trend mirrors what we've observed in the education and training sector, where independent operators are thriving far more than institutional players. It underscores a broader trend of the times: leaner, more agile individuals, unburdened by the fixed costs of staff, compliance, and management, are outperforming chain businesses weighed down by these constraints.

This might not be a bad thing. Many service industries inherently lack economies of scale. A shift back to individualized, diversified operations could, in fact, inject new vitality into the sector. In developed countries, a large number of highly skilled professionals operate as independent consultants and advisors, providing specialized services.

Mirrored trends in the US and China

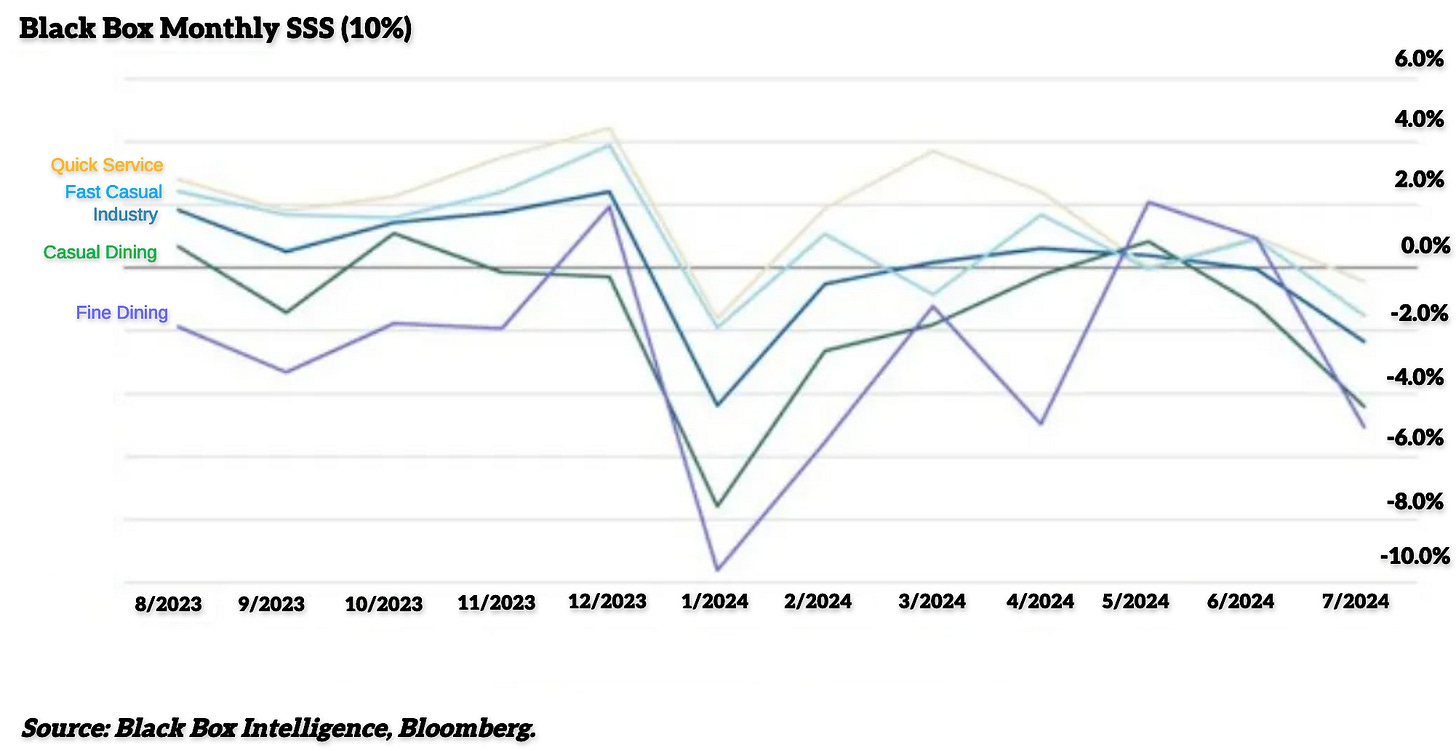

Similarly, a recent report from Morgan Stanley shows that the decline in U.S. dining has also started with high-end restaurants, with fine dining taking the hardest hit. Casual dining and fast-casual segments followed, while pure fast food fared the best. This suggests a broader trend, where the drop in high-end dining might be driven by middle-class consumers cutting back on non-essential spending. Interestingly, the wealthy aren't the main drivers of high-end dining; much of the consumption comes from the middle class reaching beyond their daily budgets. The decline doesn't necessarily indicate that the wealthy have less money but rather that the middle class is feeling the squeeze.

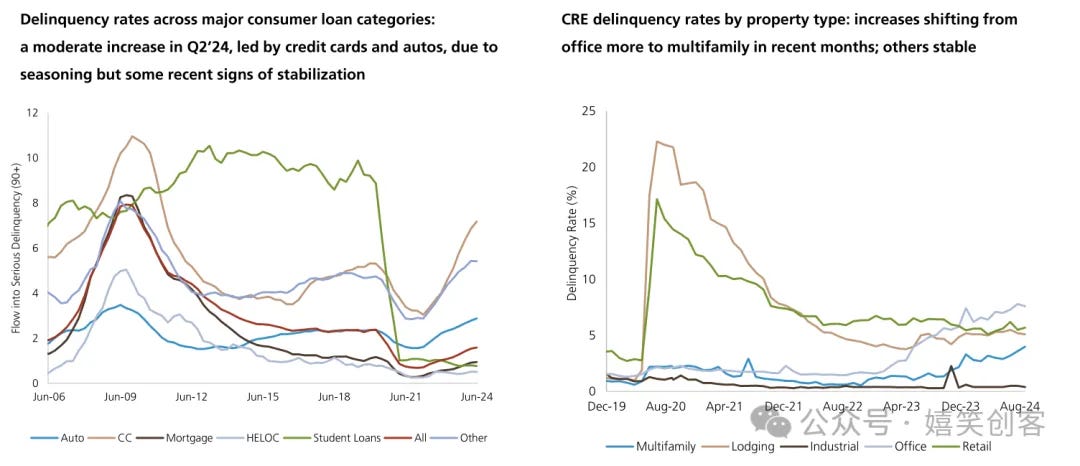

For further insight, consider U.S. delinquency rates. According to a UBS report on interest rate strategy, delinquency rates for credit cards and auto loans in the U.S. have begun to rise. Credit card delinquencies typically start with the lower middle class—those at the very bottom often don't have access to credit cards in the first place.

Reversing population flows might not be a bad thing for the downshifted economy. The narrowing income gap between urban and rural areas, as well as between cities of different tiers, isn't necessarily a negative trend, even if it comes partly at the expense of first-tier cities. If the movement of resource factors remains free, governance in inland regions keeps pace, and the business environment remains friendly, the long-term effect of free market-driven population flows could spur economic growth. The U.S. provides a fitting example with its expansion from New York to California and from Silicon Valley to Austin and Atlanta. Combined with China's lower unit cost of mobility—thanks to companies like BYD—this could mark the beginning of the next growth wave.

However, the key is that fiscally strained third- and fourth-tier cities must view this returning population as a sustainable resource, not a one-time extraction opportunity.