Three forces driving China's next decade of innovation: market scale, rapid iteration, and AI

Three Stories from the Factory Floor - Horizon Insights Research Series #3

For many of you who are investing in China, the name Horizon Insights (弘则研究), a well-respected independent research provider, shouldn’t be a new one. Founded in 2015 but with a core team that was formed almost 2 decades ago, Horizon Insights has proven one thing: despite a “young” sell-side research industry that has been dominated by high-turnover trading, hearsays, and all sorts of short-term behaviors, and despite a major market downturn in the last few years, independent research can still survive and prosper in China.

This is why when the Baiguan team met the Horizon Insights team, we instantly bonded. Both of us take pride in our respective craftsmanship. Several weeks ago, we kicked off a special collaboration series between Baiguan and Horizon Insights.

In the first post, “How has macroeconomic research misjudged China,” Horizon highlighted that traditional tools increasingly fail to track China’s new economy. Many of you asked important questions—what are the new forces, and what should we focus on now? Today’s post is a starting point to explore exactly those questions.

[You may also want to check out Horizon Insights’ equity coverage list, and their sample reports]

The following article is by Dongfan Ma, Founder & Chief Strategy Analyst at Horizon Insights.

Preface

Thank you to Baiguan for its consistent recommendation of Horizon Insights’ content. Horizon Insights’ past research approaches differ to some extent from those of traditional investment bank research institutions. Beyond fundamental macroeconomic research, we place strong emphasis on changes in industrial trends—very often, industrial trends can even significantly influence the overall macroeconomic direction. Precisely because of this difference in our research focus, over the past decade, we have provided investors with numerous perspectives on Chinese research and investment, and gained considerable recognition in the market.

We have released two articles previously. In our first article, we explained why economists have misjudged China's economy and what factors enabled China to stabilize its economy and capital market amid the shadow of a collapse.

In our second article, we discussed that the consumer sector—once the focus of the market’s greatest pessimism—has instead nurtured enormous investment opportunities over the past two years. We also explored: What defines China’s "new consumption"? And where lies the dividing line between "new consumption" and "traditional consumption"?

In this article, we want to start from the experiences of our three previous enterprise visits to explore what kind of changes Chinese enterprises have undergone over the past decade. The core issue regarding China’s economy today lies right here: behind the seemingly weak macroeconomic indicators and the rising Chinese enterprises, what economic phenomena deserve attention? Is China’s stock market a strengthening trend or an illusion of a capital bubble?

I. How China’s Industrial Innovation is Achieved – China’s Innovative Pharmaceuticals Today Are Like China’s Internet in 2000

It was 2017. We continuously visited many startups, and from a research perspective, we hoped to understand the forward-looking trends of China’s industrial and technological sectors through frontline startups. One visit that left a deep impression was to the office of an innovative pharmaceutical company. Its founder, who had worked as a leader in innovative drug R&D at a major overseas pharmaceutical company for over a decade, returned to China with great enthusiasm to start a business, planning to develop a targeted drug for a specific type of cancer.

During the conversation, we asked straightforwardly: Had this target and treatment method undergone clinical trials in the United States? What was the outcome? The founder told us very honestly: This target and treatment had indeed undergone clinical trials in the U.S., but the trials failed, and the original company did not continue to invest in advancing it. Upon hearing this, we were both surprised and curious: If the clinical trials failed in the U.S., why return to China to conduct another round of clinical trials with a very similar protocol?

The scientist’s answer was direct and insightful: First, the number of patients with this indication in the U.S. is very limited, so the efficiency of clinical trials itself is relatively low—and China is completely different. By contrast, the incidence of this indication is higher in China, and the patient base is larger. In other words, conducting clinical trials on patients with specific subtypes in China is more likely to yield statistically significant clinical results.

This conversation reminded me of the situation two decades ago, when a large number of returnee entrepreneurs came back to China to establish internet companies: They brought overseas experience back to China, but instead of simply replicating it in the local market, they combined China’s unique needs and development paths to gradually evolve business models with Chinese characteristics. We have seen China’s internet companies—in search, e-commerce, social communication—almost all gain a larger local market share than their overseas competitors in a fully competitive market.

From this, we can extract two clear signals: First, China’s market scale provides fertile ground for scaling up any advanced technology that has been validated overseas. Second, China’s unique market environment and talent structure create special opportunities for local enterprises, rather than just allowing overseas enterprises to directly copy their products for entry into China.

Returning to the innovative pharmaceutical industry, based on a series of research findings at that time, we put forward the industrial judgment and investment logic that China’s innovative pharmaceuticals would enter a “golden decade.” We could see that the golden period of this industry was not solely due to the outstanding performance of a single drug or a single technology, but because three key variables emerged simultaneously:

New Technologies: Basic technologies such as gene sequencing have gradually matured, driving technological breakthroughs in multiple areas including small molecules, large molecules, and antibody drugs, making technological iteration the core driver of industrial development.

Talent Dividend: A large number of scientists with overseas clinical and R&D experience have returned to China to start businesses. Most of these talents went abroad for study from the 1980s to the 1990s and later worked overseas, and this talent return has accelerated significantly since 2015.

China’s Market: The huge and unique market has given these returnee entrepreneurs opportunities to carry out differentiated and localized R&D and clinical verification.

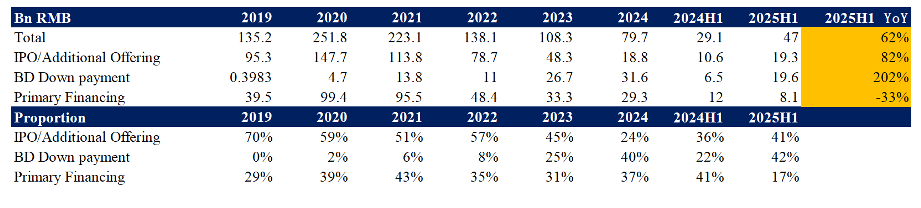

Therefore, the core message from the innovative pharmaceutical story is the enormous market. On the soil of China, overseas industrial experiences have not only not been copied blindly, but also been scaled up and accelerated in the process of localization. Coupled with supporting policies and institutional support, this has enabled China’s industrial breakthroughs and rapid development. In 2024, the upfront payments from overseas licensing deals of Chinese innovative pharmaceutical companies surpassed other financing channels, becoming the core driver of the recovery in the innovative pharmaceutical sector.

II. 3D Printing and Manufacturing Iteration: Turning “Time” into Competitiveness

The second story comes from the manufacturing and 3D printing sectors. We visited a startup engaged in robotics, which encountered a typical problem in early product development: Once a structural component entered production, it required mold opening; mold opening was costly and time-consuming—a single modification could cost 200,000 RMB and take several weeks or even months. For a startup, frequent mold opening was not only cash-burning but also slowed down the iteration cycle.

Starting from 2015 and 2016, 3D printing companies began to mature and support industrial enterprises in return. A large number of components were tested using 3D printing in the early stages, which already achieved high precision and good preliminary test results. The efficiency improvement brought by this was remarkable: The development cycle that used to take one to two months could be shortened to one week or a few weeks with the help of digital manufacturing and 3D printing. For the design side, this meant being able to obtain prototypes faster and complete multiple rounds of iteration in a shorter time.

We have also seen this advantage reflected in more consumer and industrial product categories: The iteration speed of design and R&D for toys, figurines, trendy play products, daily necessities, and even small home appliances has significantly accelerated. Take Miniso as an example: Its entire process from design, production, launch to sales is highly digitalized and flexible, enabling it to control the new product iteration cycle within one week. This forms a closed loop where market feedback quickly drives design optimization.

From a global perspective, leading 3D printing equipment companies and most of the equipment shipments come from Chinese manufacturers, and China accounts for a high proportion of related manufacturing equipment and supply chains. More importantly, China’s logistics network and manufacturing ecosystem (including supporting contract manufacturers, software and hardware suppliers, and rapid delivery capabilities) provide support for such rapid iteration. In the past, people often believed that China’s competitive advantages lay only in low-cost labor or a relatively relaxed regulatory environment. However, facts in recent years have shown that China’s core competitiveness comes more from digital capabilities, flexible supply chains, and rapid market feedback mechanisms. In other words, China has turned “time” into a competitive resource.

Therefore, the story of 3D printing points to a key word: rapid iteration. Even if a company’s initial product is not perfect, it can quickly converge to a version that meets user needs through high-frequency market verification and continuous iteration. Relying on logistics and supply chains, these products can then be promoted to global markets.

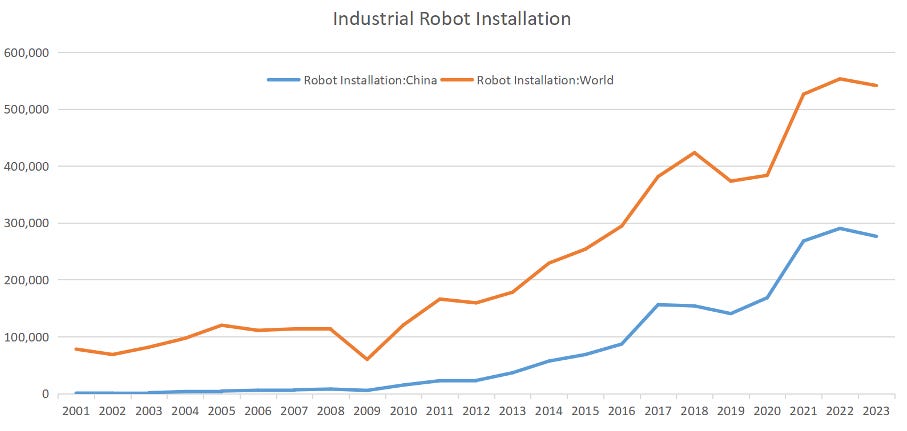

Most of the world’s consumer-grade 3D printers are produced by Chinese manufacturers. At the same time, the annual installation volume of robots in China has accounted for 50% of the global total in recent years, up from around 25% in 2015. The efficiency of the entire industrial chain has become the foundation for Chinese enterprises to achieve rapid iteration.

Horizon Insights continues to focus on the fact that a large number of mid-sized consumer products are gaining global market share through rapid product iteration—from Roborock, to Ninebot, to the well-known Miniso and Pop Mart. The competitive barrier brought by this iteration capability is actually much deeper. Horizon Insights has also released a series of in-depth and forward-looking reports to identify such investment opportunities. We welcome you to contact us to learn more about Horizon Insights’ services.

For inquiries or collaboration, contact us by replying to this email or at: subscribe@hzinsights.com

III. The Era of AI – AI Equality Driven by Diminishing Marginal Returns

The third story is related to AI. Over the past decade, we have witnessed that the core global industrial trend has stemmed from the development of the mobile internet. Meanwhile, the U.S.-centered mobile internet industry has continuously accumulated incremental commercial value globally in areas such as advertising, e-commerce, new media, and cloud computing. The fact that U.S. stock prices have risen significantly faster than U.S. GDP growth does not mean a market bubble; instead, it reflects that the revenue sources of U.S. listed companies go far beyond the scope of the U.S. domestic economy. Why is the mobile internet industry so special? Will this trend continue?

Going back to 2016, my team and I visited many Chinese AI startups. At that time, research by institutions like DeepMind drove the first wave of AI breakthroughs, and domestic AI applications initially emerged in areas such as image-oriented facial recognition and image recognition. Baidu was a major hub for AI R&D in China at that time, and we also discussed future prospects with a senior AI leader at Baidu.

Initially, our intuition was straightforward: The transition from the internet to AI might replicate the industrial pattern of the internet era—i.e., a few giants would become unshakable oligarchs due to their user scale and network effects. However, the scientist’s view differed greatly from our original understanding. He pointed out that the path of AI progress is significantly different from that of the internet: The barriers in the internet industry stem from user and content ecosystems, and as time passes, the barriers of early movers become increasingly solid; by contrast, AI evolution relies more on the popularization of methodologies and engineering, creating significant opportunities for latecomers to catch up.

Take models as an example: As the scale of model parameters grows, their marginal utility diminishes, and the increase in the number of users does not amplify the productization advantages of the model at the same rate. The phenomenon we have seen over the past two years is that after an AI product becomes popular, it does not completely form a monopoly; instead, it drives the rapid emergence of a large number of similar applications, showing an obvious diffusion effect. Many AI applications are one-to-one products for specific scenarios, and their value lies more in engineering implementation and industry adaptation, rather than simply accumulating users through network effects.

China’s advantage in this process is not just the engineer dividend. China’s industrial chain has accumulated comprehensive capabilities from chips, optical modules, and communication equipment to computing power and model training capabilities. Coupled with the return of a large number of talents with engineering experience, China has strong capabilities to transform models into industry applications and turn methods into practical products. In other words, the current stage of AI is more like a competition that relies on engineering and a large number of implementation experiments—and this is precisely where Chinese enterprises excel.

Therefore, we have arrived at an observation: The industrial characteristics of AI give it a relatively “equal” trait—not a few oligarchs monopolizing all opportunities, but a large number of engineering teams and vertical scenarios being able to compete and grow in a decentralized manner. This trait, combined with China’s talent supply, supporting industries, and market testbeds, has become an important competitive advantage for China in the AI track.

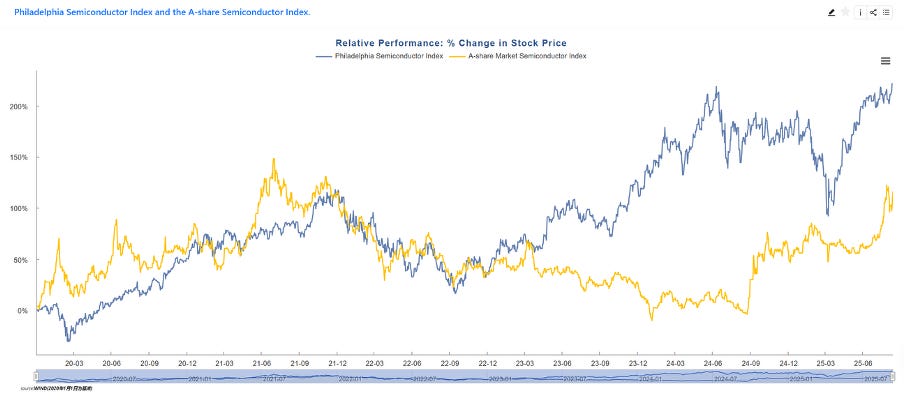

The performance of China’s semiconductor stocks once lagged far behind global semiconductor indices, but the situation changed significantly starting from 2024. The convergence of Chinese and U.S. semiconductor indices since 2024 has been one of our core recommended investment strategies.

Conclusion – The Convergence of Three Threads: Unique Market, Iteration Capability, and AI Equality

These three threads—unique market, iteration capability, and AI equality—have converged to form a competitive system unique to China at this stage. Putting these three stories together allows us to outline a relatively clear picture: When market scale, engineering capabilities, and high-frequency iteration capabilities coexist, and AI drives a more equitable technological development path, they support each other and form the core competitive advantage of China’s economy under the new industrial pattern.

These three stories precisely reflect three sources of enterprise barriers: strong user insight; barriers from experience and craftsmanship accumulated through product iteration—i.e., “know-how” barriers; and capability barriers driven by data and technological iteration. From a meso perspective, although China’s economy and the global landscape face various challenges, industrial development has actually drawn closer to China’s industrial sector. The pessimism about the macroeconomy and the divergence between traditional economic narratives and micro-level realities have precisely become the source of huge investment returns from Chinese assets over the past two years, and also represent the enormous research value that Horizon Insights brings through its meso-level industrial perspective.

For inquiries or collaboration, contact us by replying to this email or at: subscribe@hzinsights.com

About Horizon Insights —Established over a decade ago, Horizon Insights is dedicated to delivering in-depth, cycle-aware insights into Chinese assets. Our core team comprises well-regarded investment research professionals who have been working closely together for almost two decades and have earned the trust of over 1,000 institutional and professional investors worldwide. Our research is recognized for its independence and foresight, grounded not in noise but in long-term conviction and depth. We’re grateful to connect with you through this Newsletter, and we look forward to ongoing, thoughtful dialogue.